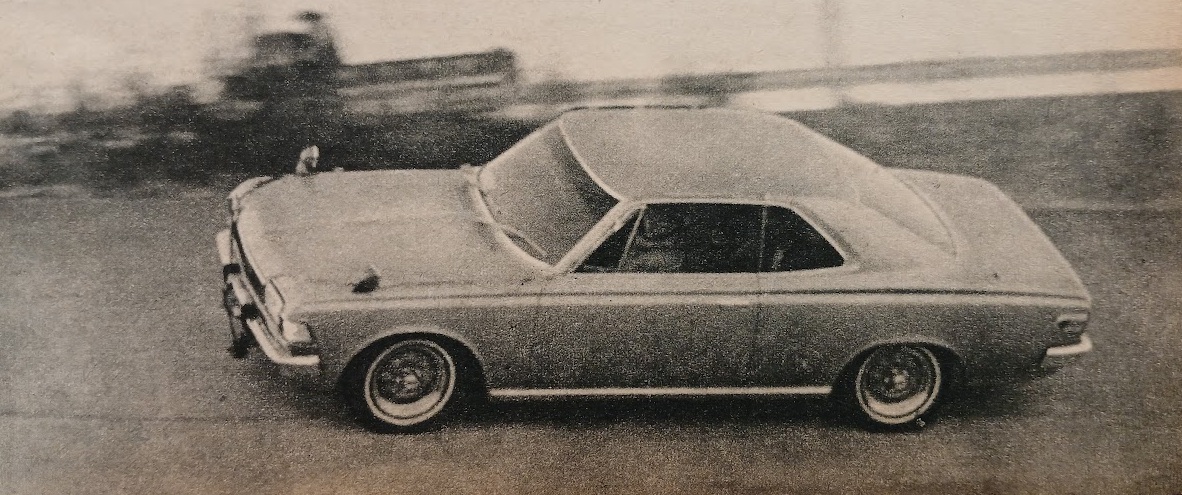

Toyota Crown Hardtop SL (1969)

Publication: Motor Fan

Format: Road Test

Date: January 1969

Author: Kameo Uchiyamada, Osamu Hirao, Eiichi Kumabe, Masahi Kondo, Kenji Higuchi, Hiroshi Hoshijima, Kunitaka Furutani, Jun Narie, Yasuhei Oguchi, Taizo Tateishi, Kazuo Kumabe, Akio Miyamoto, Mineo Yamamoto, Atsushi Watari, Kenzaburo Ishikawa, Toshihide Hirata, Minoru Onda, Motor Fan Editorial Staff (uncredited)

Growing Demand for Hardtops

Magazine: As is our usual practice, we would like to ask Mr. Uchiyamada to start by talking about the aims of the development and how the project came about.

Uchiyamada: Talk of “wanting a mid-size hardtop” goes back to around 1963, when I first came to be in charge of the Crown. At the time, however, hardtops were still widely regarded as specialty cars, and there was a strong feeling that they would not sell well. For that reason, we were unable to move forward quickly.

Looking overseas, however–particularly to the United States–we began to see a steady increase in the sales of hardtops. Even in the case of the Corona, hardtops accounted for around 9% of sales at first, but by 1967 that figure had already risen to about 16%. Seeing this trend, we decided to reexamine the hardtop market in earnest.

When we analyzed the Crown’s customer base, we found that roughly 85% of demand came from corporate or industrial users, with private owners accounting for about 15%. Moreover, about 60% of those corporate customers actually drove the cars themselves. In other words, even among corporate users, more than half were effectively owner-drivers.

In numerical terms, the current mid-size car market is about 12,000 units per month, and roughly half of those are driven by the owners themselves. We believed that if a hardtop were planned specifically with these self-driving customers in mind, there would be substantial demand on the market. That thinking ultimately led to the Crown Hardtop.

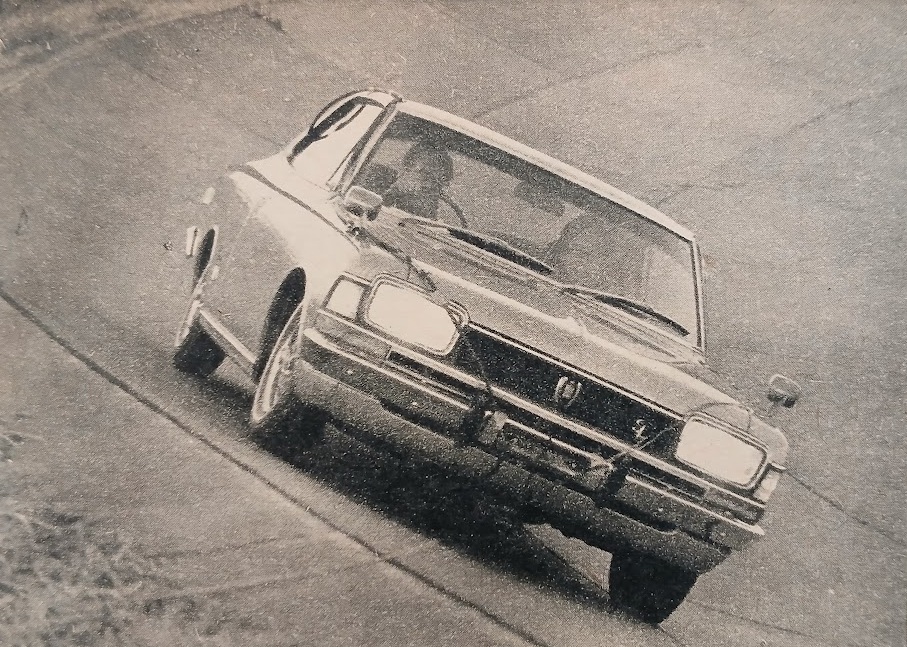

Hirao: We’re told that improving the styling was one goal, but what was the reason for shortening the car by 55mm?

Uchiyamada: We wanted to improve maneuverability in city driving for customers who would drive the car themselves. For example, we thought about making parking easier, and allowing more relaxed overtaking. To that end, we reduced the overall length. The SL specification is shortened by 55mm, and the standard model by 80mm.

Kumabe (Eiichi): We cut the length from the rear. The aim was to emphasize a long-nose effect.

Considering Rear-Seat Comfort as Well

Magazine: In adopting the hardtop body, what kinds of technical changes were required? For example, in terms of the engine, the body structure, or the difficult task of eliminating the center pillar…

Uchiyamada: I touched on this briefly earlier, but we did not think of this car simply as a sporty leisure vehicle. Rather, we envisioned it as a substantial, capable car that could also be used in formal settings, and we focused our aims accordingly. That meant that while the front seats were of course important, we placed particular emphasis on the rear seats, and making them suitable for adults to sit in comfortably. Traditionally, hardtop styling has tended to place such an emphasis on appearance that rear-seat comfort was sacrificed. This time, the challenge was how to improve the styling without compromising rear-seat accommodation.

As for the body structure, eliminating the center pillar naturally raises concerns about overall body rigidity. Another issue is that with only two doors, access to the rear seats can become difficult. To address these points, we paid particular attention to the strength and rigidity of structure around the rear quarter panels. We also lengthened the doors, and carefully considered the amount of clearance when tilting the front seats forward to allow entry to the rear.

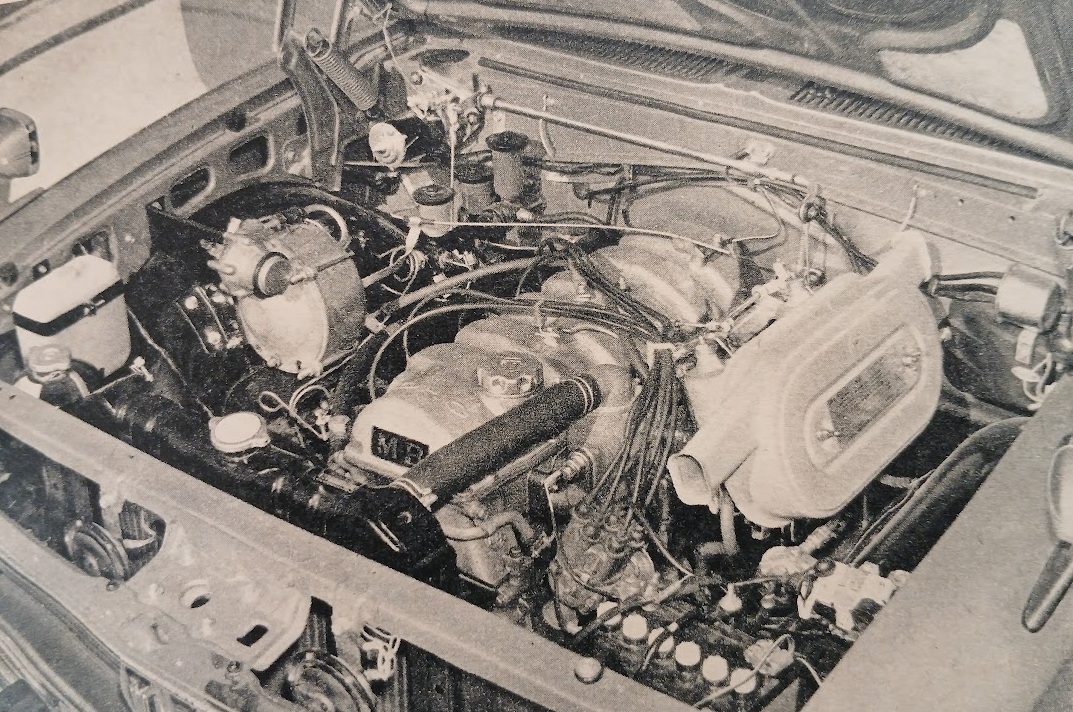

The engine itself is the same basic unit used in the existing Crown S, but with substantial revisions. The combustion chamber was completely redesigned, and the exhaust and carburetor were reworked. The goal was to improve low-speed torque in particular. The previous Crown S was positioned as a sporty car, but this time the objective was greater practicality. We developed this new combustion chamber design with that in mind. As for the suspension and running gear, we have essentially carried over the sedan’s setup as-is.

Hirao: As for the styling, it feels as though a distinctly “Toyota” form has taken shape. Starting with the Corolla, this semi-notchback form–if that’s the right description–continues here, and the rear treatment in particular has a similar look across the series.

A Style with a Distinct Identity

Uchiyamada: This was also the first time we formally adopted a collapsible steering column. We struggled quite a bit on the testing side, and it took a great deal of time to achieve the required energy-absorption characteristics.

Because of design requirements, we also moved away from conventional wheels with hubcaps and adopted disc wheels for the SL. To incorporate brake ventilation openings into the wheel itself, we had to deepen the pressing, which raised strength concerns, and resolving those took considerable effort as well. In this case, the engineers really had to work hard to satisfy the demands of the design team.

Kondo: Setting aside cost and manufacturing constraints, I imagine you must have considered extending the rear window further into the side. Would that have improved the styling, or made it worse?

Uchiyamada: Our aim with the styling was to give the car a strong sense of individuality, and the wide rear-quarter treatment was one of the central themes of this model.

Higuchi: You’re seeing this trend more and more in American cars as well—rearward visibility from the back seat becoming increasingly limited. It reminds me of the old landau style, almost like a horse-drawn carriage.

Uchiyamada: From the customer’s point of view, I sometimes think it may actually be preferable not to be able to see too much out to the side.

Higuchi: For a light, nimble car, narrowing the quarter pillar makes sense. But for a more luxurious car, I think this approach may actually be better.

Hirao: Do you really need the triangular vent window?

Uchiyamada: Because the glass area is so large, it serves as a guide for raising and lowering the window.

Hoshijima: From a safety standpoint, recent cars seem to be adopting thicker rear pillars. American cars, in particular, appear to be reinforcing that area, perhaps to improve impact resistance.

Uchiyamada: When we conduct side-impact tests, the structural members around the rear quarter contribute significantly. The same is true in rollover tests—there are various ways to simulate a rollover, of course, but in those situations as well, the rear quarter structure plays a definite role.

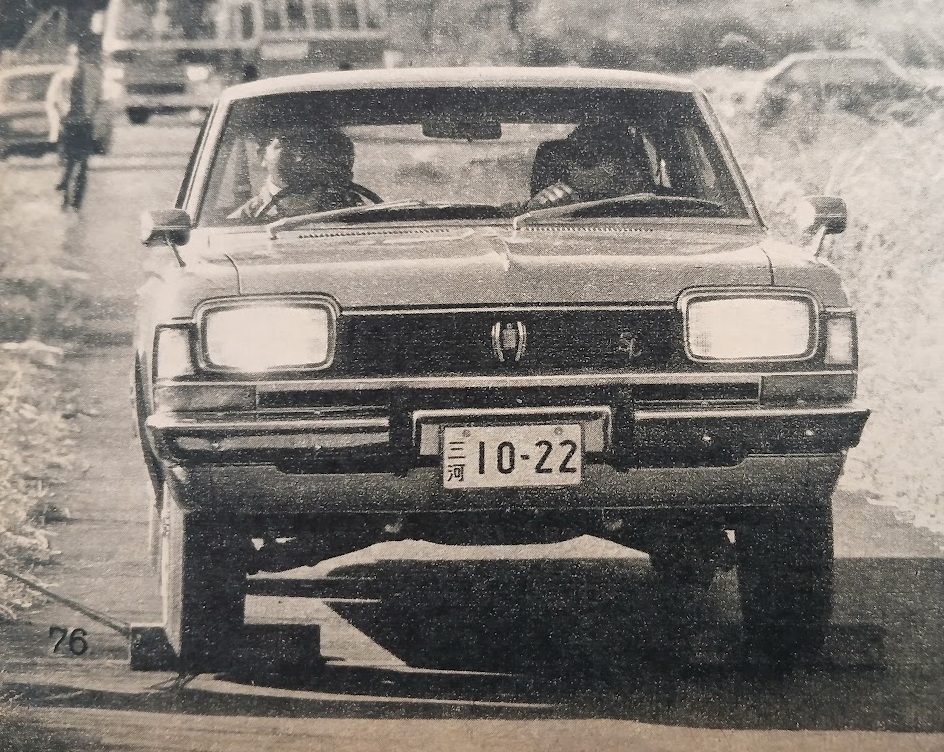

As for the unusually shaped headlamps, that design actually dates back to the development stage of the New Crown sedan project. The concept was already finalized at that time; this is just the first opportunity it’s had to see the light of day. (laughs)

Well-Integrated Disc Wheels

Hirao: Are those the same headlamps used on the Century?

Uchiyamada: No, they’re different. This is a semi-sealed type. Inside, there’s a separate bulb, and the space around it is filled with nitrogen to prevent fogging. The lens sits outside of that.

Higuchi: When the doors are lengthened, side impacts become an issue. In the past, when such cars were struck from the side, the body would deform very easily and intrude inward. I’ve heard that in the US, a great deal of attention is now being paid to strength in this area.

Uchiyamada: In side impacts, the most helpful element is the perimeter frame. Next, the door itself deforms, and then the load is taken by the front seat, which absorbs the impact. Door-latch mechanisms have also improved greatly, so the doors are far less likely to spring open in a collision, which is another advantage.

Kumabe (Eiichi): We carried out a full series of safety tests, and in both side-impact and rollover situations, the locks did not release. The doors remained firmly closed.

Hoshijima: With older American cars, especially the pillarless types, you often get the impression that the fit of the doors deteriorates over time.

Uchiyamada: I agree completely. With four-door hardtops that lack a center pillar, even driving on ordinary Japanese roads, you hear creaks and groans. You start to wonder whether, over time, the doors might come off altogether.

Higuchi: When you slam the door shut on a pillarless hardtop, the whole body seems to wobble.

Hoshijima: Are the headlamp-surround components interchangeable with the current Crown passenger cars?

Uchiyamada: The headlamps and this grille are interchangeable as a set. That said, if you were to install them, you’d probably need to submit a modification notice. (laughs)

Kondo: Speaking of what you mentioned earlier, the disc wheels strike me as an excellent example of how mechanical engineering and design have been very successfully harmonized. I really admire that as an example of bringing together engineering and design.

Uchiyamada: For those wheels, the idea was: “Make it look exactly as the design intends, and still give it fatigue strength.” That meant we had a lot of trouble keeping the strength without losing the shape. The other issue was the color. The design goal was to give it a magnesium-like look, but if we used actual magnesium, we wouldn’t make any money on the car. (laughs) So we struggled quite a bit to create a magnesium-like color and texture. In reality, it’s just ordinary steel.

Minimum Weight Per Horsepower

Magazine: All right, then let’s move on to the data. First, can you share the results of the Hirao laboratory’s power performance testing?

Furutani: In terms of vehicle weight, the catalog figure is 1,295kg. During testing, the driver, test engineer, and instruments added another 185kg.

Standing-start acceleration performance is 0-50m in 4.9 seconds, 0-100m in 7.6 seconds, 0-200m in 11.8 seconds, and 0–400m in 18.7 seconds.

In terms of time to speed, the car reached 40 km/h in 3.7 seconds, 60km/h in 6.5 seconds, 80km/h in 10.6 seconds, 100km/h in 15.9 seconds, and 110km/h in 19 seconds.

Overtaking acceleration was as follows: starting in third gear from 30km/h, the car reached 40km/h in 3.5 seconds, 60km/h in 7.8 seconds, 80km/h in 12.4 seconds, 100km/h in 17.8 seconds, and 110km/h in 21.2 seconds. In top gear, starting from 40km/h, it reached 50km/h in 5.3 seconds, 70km/h in 12.4 seconds, 90km/h in 19.5 seconds, and 110km/h in 27.1 seconds.

The figures themselves are fairly good, but by contrast, in terms of the feeling you get while driving, the 4.9 second 0-50m run and 18.7 second 0-400m run don’t give the sense of sudden acceleration you get from a GT or a sporty car. Once the speed builds up, though, the car pulls strongly, and there’s a kind of underlying strength. I think it makes highway driving very comfortable.

The vehicle weighs around 1.3 tons, so considering that it’s pulling a fairly large body, I didn’t expect such good numbers. In reality, you don’t really feel the true speed that much; the performance is better represented by the numbers.

Magazine: We understand one of the aims was to make the power performance fairly strong.

Uchiyamada: One of the goals was to make this model’s performance the best among the Crown series. So in terms of weight per horsepower, it comes out to 10.28kg/ps. The Taunus 20M hardtop is 13.0kg/ps, the Taunus 20MTS hardtop is 12.44kg/ps, and the Opel Rekord coupe is 12.0kg/ps. Even in the prototype stage, we worked on the engine to reduce the weight per horsepower as much as possible.

Attracting Younger Buyers As Well

Magazine: Mr. Narie, how did it feel to drive?

Narie: It’s genuinely exciting that a luxury personal car like this has appeared. The look alone is attractive, and young people naturally get drawn to it too. What I want to say is that the SL should perhaps be made a bit calmer.

Not everything needs to be sporty; using the standard Crown steering wheel and other fittings would also be fine. I think it would be better if there were a version that was more relaxed and comfortable to ride in. At first, I thought that because it has the “S” engine it would be very “hot” and aggressive, but it was actually very easy to drive and I liked it a lot.

Magazine: Next, let’s move on to the fuel economy tests conducted in the Oguchi laboratory.

Oguchi: Since the Corona Mark II test, we’ve been taking a new type of fuel economy measurement. We’re conducting two kinds of tests: the standard steady-speed fuel economy test that’s generally used, and a model test that reflects real-world driving in urban areas.

Starting with the steady-speed figures, we measured 14.5km/l at 40km/h; 13.2km/l at 60km/h; 11.5km/l at 80km/h; and 9.5km/l at 100km/h. Next is the model-run economy: we simulate city driving conditions by repeatedly driving over a 400m section, accelerating up to a steady 40km/h or 60km/h cruise and then braking. When the top speed is set at 40km/h, the average speed comes out to 22.0km/h due to the braking to simulate traffic signals, and fuel economy is 8.6km/l. If we set the top speed to 60 km/h, the average speed is 25km/h, and fuel economy becomes 6.8km/l. For the steady-speed test, we also plot the results on a comparative fuel-economy curve to see what the economy results indicate about the car’s character.

If you plot the steady-speed figures at 60km/h on that curve, which represents the average, anything above the curve can be considered passenger-sedan-like. GTs and sports cars fall below the curve. Given this car’s standing-start acceleration of 0–400m in 18.7 seconds, you might expect the Crown to fall below the curve, but it doesn’t. It comes out above, showing fuel economy similar to a sedan. That fits the earlier point: it isn’t intended as a sports car or a dedicated grand tourer. It’s meant for formal use, and that intention shows in the numbers.

It seems that the combination of enlarging the carburetors slightly and making changes to improve low-speed torque have resulted in fuel economy that is quite sedan-like.

Magazine: Do your in-house figures match these?

Kumabe (Eiichi): Our in-house figures were the same at 40km/h–14.5km/l. At 60km/h it was 13.3km/l; at 80km/h, 11.4km/l; and at 100km/h, 9.4km/l. So they match very closely.

Impressive Noise Control

Magazine: Next, vibration and noise. Let’s please hear the report from the Watari laboratory.

Tateishi: Here are the results. The sprung-mass natural frequency is 1.3cps at both front and rear, and the unsprung-mass natural frequency is 10.0cps at both front and rear. Those are very appropriate values for this class.

Interior noise was recorded at 60 hones at 40km/h, 64 hones at 50km/h, 66 hones at 60km/h, 67 hones at 70km/h, 69 hones at 80km/h, 70 hones at 90km/h, 72 hones at 100km/h, 72 hones at 110km/h, and 74 hones at 120km/h (all measured on the A scale). Exterior noise, measured at a steady 50km/h in second gear, is 76 hones. Under acceleration from the same speed, it rises to 82 hones.

I think the interior noise is very good, sitting close to the lowest line on the Motor Fan evaluation zone. As for the exterior noise, I’d personally like to see the acceleration noise reduced to about 80 hones, or even a little below. I’d say that the cabin is quiet, but the exterior noise is somewhat high. Overall, I’d say the noise countermeasures have been very well executed. Those are the figures we recorded. I would only add that, in cornering, I do feel the amount of roll is a bit larger than I’d like.

Magazine: Dr. Kumabe, what was your impression after driving this car?

Kumabe (Kazuo): My impression was mainly of the ride comfort, and there are a lot of good things to say in that regard. Also, stylistically, aiming for sportiness while still remaining fundamentally a sedan—one could say it’s a successful approach to a new sedan type.

Miyamoto: This car weighs about 1.3 tons, and you can really feel how composed it is when you drive it. Cars with this kind of frame are rare these days, but I think a car like this should prove very comfortable in long-distance driving. Also, as was mentioned earlier, the rear overhang is quite short, so even someone older like me could use it in town on a daily basis without issue. It could be driven by a chauffeur or by one’s self, and as Mr. Narie said, I think it would also appeal to younger people.

Also, the engine is a six-cylinder, and it has a real sense of torque–you might say that it’s very tenacious–and it’s quiet as well. Hardtops are in fashion now, and I have the feeling this one will sell fairly well.

Magazine: Dr. Yamamoto, what was your impression after driving it…?

Yamamoto: I rode in both the front and rear seats, paying attention to vibration and ride comfort. What I noticed most was that there’s a fair amount of low-frequency motion, and the damping is very good. So, as Dr. Kumabe said, I think the ride comfort can be called excellent. The motions are slow and relaxed. Perhaps it’s thanks to the perimeter frame, but the torsional rigidity also seems fairly high. Whether that’s the reason or not, I think the vibration frequencies become fairly low–torsional vibration frequency in particular seems extremely low, compared with previous models…

Uchiyamada: Regarding torsional stiffness, it comes from the frame and the body working together. In that respect, the hardtop should actually have a slightly greater amount of torsional flexibility than the sedan.

SL-Specific Muffler

Yamamoto: I think the isolation is also good. In any case, it’s very comfortable.

Uchiyamada: Earlier I mentioned the low-frequency vibrations. We actually changed the body-mounting system slightly from the sedan. We added one more body mounting point between the front pillar and the rear quarter. That was the approach we took.

Magazine: We’d like to hear your impressions, Dr. Watari, including your thoughts on the styling.

Watari: When the original Arrow Line Corona evolved into the Mark II, its styling improved considerably, but I feel this hardtop is the one that’s been done the most pleasantly of all. The styling is really quite good.

As for how it drives, I expected that making it a hardtop would involve a push toward a somewhat aggressive, sporty feel. But surprisingly, the interior is very quiet–so quiet that it sits right on the lower limit of Motor Fan’s evaluation zone. What you notice most is that you don’t have to shout to talk between the front and rear seats. That means you can drive while conversing with rear-seat passengers without getting tired.

In terms of ride comfort, it seems that the goal here was high-speed safety. The roll and other motions in response to the steering are quite good. And even on rough cobblestone-like roads, the unsprung vibration and so on are nicely controlled, so overall it feels very well engineered. The seats feel good too, but if older people like myself are going to be riding in the back, it might be better to redesign the rear seat shape so that the thigh support doesn’t drop away toward the front of the cushion.

Up front, I feel it’s quite good, but the shift lever seems to be set a bit too far back.

Magazine: You mentioned the cabin is very quiet—did you have to work hard on soundproofing?

Uchiyamada: We basically handled the noise issues the same way as with the sedan. But for the SL, because we didn’t want to reduce horsepower, we made a model-specific muffler. The challenge was to keep the power from dropping while also preventing the noise from rising.

Watari: Even with that, it’s incredibly quiet. Among domestic passenger cars, this is the quietest one I’ve heard.

Heavy Yet Precise Steering Effort

Magazine: Next, we’d like to present the stability results from the Kondo Laboratory and move on to that discussion.

Kondo: The stability and handling tests in Motor Fan’s road tests have become fairly static in recent times. They’re things we feel we must do, and omitting them is unrealistic. But I must say we’re not keeping pace with the recent advances in the field. On that point, all of us involved, myself included, are frankly dissatisfied.

For example, we could test high-speed “settling” behavior, or measure frequency response when steering input is applied. We could test straight-line directional stability with the steering locked. Or we could explore extreme performance–at-the-limit performance, so to speak–by running intense slalom trials or hard cornering tests. We know we could do these things, but they take time and manpower that we simply don’t have. That’s why, with some reluctance, we’re still using the old, fixed testing methods.

We haven’t finished organizing this car’s test data yet, so we unfortunately can’t present it to you, but from what we’ve seen so far, I can sum the car up in one word: this hardtop is excellent.

That said, the steering effort at standstill is heavy. This is my general belief, but I really want to see steering effort at a standstill become lighter. When you drive a car, this is the only thing that still feels like a real physical burden. When this topic comes up, many people say, “Just add power steering.” But if you consider what power steering actually entails, I feel that apart from reducing standstill steering effort, it often has negative effects. I think we should consider an approach that specifically only reduces standstill steering effort.

Watari: What you’re saying is absolutely right. You don’t need anything other than standstill steering assistance; everything else is better left alone.

Uchiyamada: Actually, this car offers power steering as an option. Including the sedan, we’re shipping about 300 units per month equipped with it.

If you say there are drawbacks to power steering, it’s probably because of poor returnability, and a certain time lag or lack of responsiveness—those were two issues we had in the past. So we developed a nozzle-flapper control valve. With that change, the steering no longer has that problem of poor returnability. The frequency response and follow-through feel much better, and lane-changes at speed have become a lot easier. I’d really like you to try it. It takes a day or two to get used to, but power steering is like a drug (laughs): once you’ve used it, it’s hard to go back.

Slow-Speed Brake Response Is a Bit Delayed

Magazine: Mr. Kondo, what was your impression after the test drive, and can you describe how the steering feels?

Kondo: Regarding the steering, apart from the heavy low-speed effort I mentioned, it’s good for highway driving.

Now, about the brakes: when you step on them at high speed, they feel reassuring and very pleasant. But at low speeds, the brake response, to me, feels a bit delayed, and that bothered me a little. I’m sure Ishikawa will have something to say about that…

Ishikawa: Yes, that’s exactly how it feels. The reason is that eliciting the initial response requires quite a lot of force. In a normal car, especially one with disc brakes like this, you’d expect braking to begin with around 1-2kg of pedal pressure. But this car needs about 4.5kg for the front brakes to respond, and 7kg at the rear. In other words, unless you press around 7kg, you don’t really feel like the brakes have “engaged.”

You see, the front uses a Hydro-Vac-type servo. I suspect that’s where the delay comes from. So it’s difficult to guarantee a certain amount of braking for a given pedal force, or to guarantee a specific deceleration rate. You can’t easily set a sensory benchmark like, “If I press this hard, I’ll get that much braking.”

When we did road tests, we found that maintaining a steady 0.2g or 0.4g deceleration rate–something we’d never had trouble with before–was surprisingly difficult. You press the pedal and think, “Is this enough?” and then the braking gradually strengthens. Normally, you’d expect the brakes to become more effective right at the end, just before you come to a stop. But in this one, instead of that clear bite, it feels… kind of drawn-out, almost sluggish.

So I think what Mr. Kondo described as “feeling like there’s a delay” is something anyone would notice while driving. Instead of using a Hydro-Vac-type system, there are power-assist units that sit in front of the master cylinder, right? I wonder why something like that wasn’t used…

That’s related to brake design in general, but in the Crown specifically, this model uses disc brakes in the front and a duo-servo setup in the rear–two brake systems that, in a sense, contradict each other. That’s something I’d like to ask about as well.

Uchiyamada: The way we designed the brakes is: front disc brakes with a booster, and rear duo-servo brakes without a booster. We’re thinking in terms of two independent systems, front and rear.

We could have gone with rear disc brakes and a four-wheel disc setup, of course, but when you add rear discs, it becomes difficult to incorporate a parking brake that works well. That’s a flaw of disc brakes. Unless you pull the parking brake very hard, the parking brake doesn’t hold. That’s one problem.

The other issue relates to structure: the rear brakes are mounted on the rear axle shaft. It’s a semi-floating setup, so when you brake, the axle flexes. With that kind of flex, if you fitted disc brakes, you would get kickback. To avoid that, you’d need a much stiffer axle structure—so we decided to stick with the current setup.

Then, as for the “brake feels delayed” issue: just as Mr. Ishikawa said, the booster doesn’t really kick in right away. Only when the pedal force reaches about 4kg does the booster start to work, and that’s what makes it feel delayed.

Another factor is the way the brake booster is designed to come in. It’s intentionally tuned to be somewhat gradual rather than sudden. If it engaged sharply, it might feel like the brakes grab too violently, and we didn’t want that. That’s why it feels the way it does.

But the world is gradually getting used to brakes that bite quickly, so eventually it may be better to design the system to feel sharper.

Dead Space in the Rearview Mirror

Magazine: Let’s continue by sharing the data gathered at the Ship Research Laboratory.

Ishikawa: As usual, I’ll start with the vehicle weight. With the spare tire and tools, it comes to 1320kg. The nominal vehicle weight is 1295kg, so that’s about 25kg heavier.

As for the weight distribution, we measured 356kg at the left front wheel and 366ks at the front right. The rear left is 297kg and the rear right is 301kg, so the left-right difference isn’t particularly severe. The front is slightly heavier on the right side, but only by about 10kg. Compared to similar cars from other companies, that’s essentially negligible. In percentage terms, the distribution is 54.6% front, 45.4% rear.

With one or two people in the front seat, the front-to-rear distribution doesn’t change. With the full five-person load, the rear becomes a little heavier, roughly 51% to 49%, so you can consider it essentially a 50:50 split.

Next is wheel alignment. At the front, both toe-in and camber are only very slight. At the rear, camber is almost zero, but it’s just slightly toe-out. We took measurements with both the one-person load and the five-person load, but the distribution hardly changed.

Next, brakes. The pedal stroke at the start of braking is about 27mm at a force of 4.5kg, and the rear brakes engage at around 8kg, when the stroke becomes about 46mm. The force required for 0.6g deceleration is shown as 21kg, and at that point the stroke is about 67mm.

Once the rear brakes are in effect, the servo disengages at around 0.6g, at a pedal force of roughly 30kg. The spring constant over that range is about 0.7kg/mm, which is a normal value for modern power-assisted brakes, but it does feel somewhat soft. The front-to-rear brake force distribution is roughly 6:4.

The servo’s resting point is more or less in that 30kg pedal force range. The figure of 21kg for 0.6g deceleration mentioned above was from our bench test, but in the road test, 0.6g deceleration from 50km/h also came out to around 20kg of pedal force.

The parking brake balance is fairly good in both forward and reverse. The operating force to produce 0.2g deceleration is about 12kg in the forward direction and 16kg in reverse.

We also measured operating force for the other driving controls. The shift lever is a 4-speed floor shift. It takes about 2–2.5kg to engage each gear, and about 2.5–3.5kg to disengage. Reverse requires a lateral movement of about 0.5 kg. Once in that gate, the effort to engage reverse is somewhat high, at about 6.5kg, and disengaging it takes about 2kg.

The clutch pedal takes around 10kg to disengage and 7kg to engage. Pushing the accelerator pedal to the floor takes about 3kg of force, but in normal acceleration you use about 2–3kg. These are the values we measured.

Magazine: Now, Dr. Hirata, please share the field-of-view measurement results you conducted.

Hirata: The field-of-view measurements were taken in three seat positions: the seat pushed all the way forward, all the way back, and in the middle. In the central position, the height from the ground to the eye point is 123.4cm. The distance from the camera lens cap to the front glass is 42cm. The distance to the center of the rear-view mirror is 51cm.

The visible range through the front window, in the horizontal direction, is 33° to the right and 48° to the left, for a total of 81°. In the vertical direction, it is 10° up and 10° down, for a total of 20°.

The visible range through the rear window is 6° to the right and 45° to the left, for a total of 51°. Vertically, it is 1.5° up and 5.5° down.

The wiper sweep covers 22° to the right and 34° to the left, for a total of 56°. Since the rear-view mirror is mounted directly in the line of sight, it seems to reduce visibility considerably.

In all, the total blind spot with the seat in the center of its travel is 103°, of which 43° is forward. Expressed in steradians, the forward blind spot is 1.17 steradians, of which the front window accounts for 0.517. The wiper sweep covers 0.344, which clears about 67% of it. The rear window is 0.141 steradians.

Magazine: Dr. Yamamoto, do you have any comments regarding the field of view?

Yamamoto: The rear visibility is very narrow, so the field of view is not particularly good. However, among coupes and similar cars, I think this is a typical value.

And now, since Hirata-kun is highlighting it, I’ve noticed that Toyota’s cars have the rear-view mirror positioned noticeably lower than other cars. Because of that, a dead zone is created behind the mirror, and visibility is reduced. Toyota’s rear-view mirrors are generally placed right in the plane that includes the driver’s line of sight.

Bumper Guards Only On the SL

Magazine: Next, could we hear from the Higuchi laboratory about the dimensions and interior arrangement?

Onda: The Higuchi lab took the measurements as usual, but since the initial explanation already included very detailed numerical values, I’ll just mention one or two additional things. First, and I’d actually like to be corrected on this, but it seems that the only highest-grade SL model has overriders on the front bumper, and not the others. This was clearly a styling decision. The streamlined fender mirrors give a sporty impression and a very premium feel, which matches the car’s intended image.

The rear reflectors looked as if they might be lit from the inside like tail lamps, but they weren’t, so that was a little disappointing. The front ones are illuminated, but the rear doesn’t go that far–was that because it wasn’t necessary, or was it a deliberate omission? I’d like to hear the reasoning.

Also, it’s difficult to effectively utilize the trunk space. That’s because the ventilation ducting takes up space on both sides, so the spare tire was pushed into the center. I think this is a result of prioritizing style.

Also, the instructions for the three-point seat belts describe several ways to stow them, but in practice, the belt just hangs loosely because there’s no pillar, and that feels awkward. The manual says you can fold it down with the seatback and store it without removing it, but I feel there should be a more proactive solution, like winding it up into the headliner.

Uchiyamada: The first point was about the bumper guards. The reason the front bumper guard is fitted only to the SL and not the standard model is simply to create a difference in image between the cars. In that sense, it’s purely decorative.

As for the seat belts, our thinking is that the belt coming from above and the belt coming from below should never be separated–you should always have them together. If you were to separate them and roll the belts up, you’d have to add a retractor at the bottom as well; otherwise, the lap belt would get caught when opening and closing the door. So, the idea is to keep the belt close to the body at all times, so that it stays taut and doesn’t get caught in the door.

One point on the seatback: the standard headrest regulations call for a minimum height of 650mm. In this car, the measured value is 670mm, so we’re planning to reduce the height slightly within the margin.

You’re right about the spare tire–because of the ventilation duct layout, it had to be laid flat, and since we shortened the rear length by 80mm, it doesn’t fit in the same place as the sedan. However, I think the trunk space is still adequate for a hardtop.

Finally, regarding the side reflectors on the rear fenders, if we export the car to the US, we can install lamps in them. But domestically, due to regulations, we cannot include lamps. The mounting provisions are there, but we can’t install them in Japan.

Magazine: Now, Mr. Higuchi, could you talk about safety and maintenance?

Higuchi: I’ve been working on ways to evaluate safety for about three and a half years. It started when cars like Fiat’s Sigma and other safety-focused prototypes began to appear. The editorial staff asked us to start examining this area, so we did. Back then, there were almost no cars equipped with seat belts, so we used a five-point scoring system. The average score at that time was around three points.

But since the end of last year, Japanese cars have rapidly improved in safety features, and the scoring standard has risen. The Crown sedan already scored the highest among domestic cars, but this hardtop has even more safety equipment–the collapsible steering wheel and other features–so the scoring ended up being too lenient. As usual, we evaluated 30 items on a five-point scale. Normally, with 30 items, a score around 90 would be average, but this car scored 138 points. Converted to a 100-point scale, that’s 92 points. It’s a level that exceeds the standard, and I think we’ve reached a point where we should no longer be changing the scoring criteria.

There is only one item that scored three points out of five. That was for the “provisional gas” or exhaust gas treatment system. If there is a visible device installed, the score is higher; if not, it’s lower. That’s why this one item got three points. Of the 30 items, 19 scored five points and the remaining 10 scored four points, so that really says it all.

In terms of maintenance, comparing this car with the Corona, it looks like Toyota is aiming to standardize the maintenance schedule across models. After the first 1,000km, it calls for a minor inspection. After that, maintenance is required every 5,000km.

Magazine: I believe that covers everything. Lastly, could you tell us about production plans? Specifically, how many units you’re aiming for?

Uchiyamada: By the end of last year, I believe we exceeded 3,000 units. This year’s plan is about 2,000 units per month.

Magazine: Thank you all very much.

Postscript: Story Photos