Toyota Celica 1600GTV vs. Nissan Bluebird U 1600SSS-E (1972)

Publication: Car Graphic

Format: Group Test

Date: November 1972

Author: “C/G Test Group” (uncredited)

Comparison Test: Toyota Celica 1600GTV vs Nissan Bluebird U 1600SSS-E

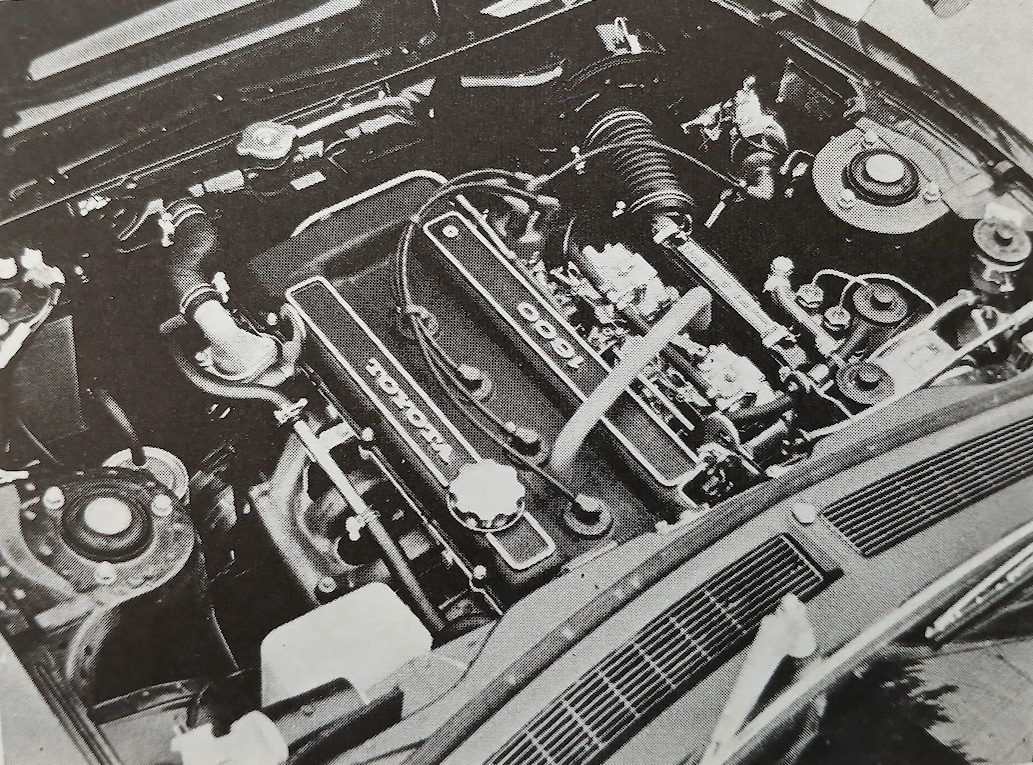

The Celica GT and the Bluebird U 1600 SSS compete in the same segment in terms of character and price class, and noteworthy variations aimed at enthusiasts have recently been added to both series, namely the Celica GTV and Bluebird U Hardtop 1600 SSS-E featured in this comparison test. Both are equipped with 115ps engines and 5-speed gearboxes, though the Bluebird’s hardtop body is slightly larger and weighs about 60kg more. Naturally, the Celica GTV is equipped with the same DOHC 1588cc engine and two Mikuni Solex 40PHH twin-choke carburetors as the GT, while the Bluebird U 1600 SSS-E is equipped with the same Bosch electronic fuel injection unit as its big brother, the 1800 SSS-E. As mentioned, both cars have a maximum output of 115ps, but the power peak is 6400rpm for the Celica and 6200rpm for the Bluebird, and the engines’ maximum torque figures are 14.5kgm/5200 and 14.6kgm/4400rpm, respectively, so it can be said that the DOHC Celica is the higher-revving car.

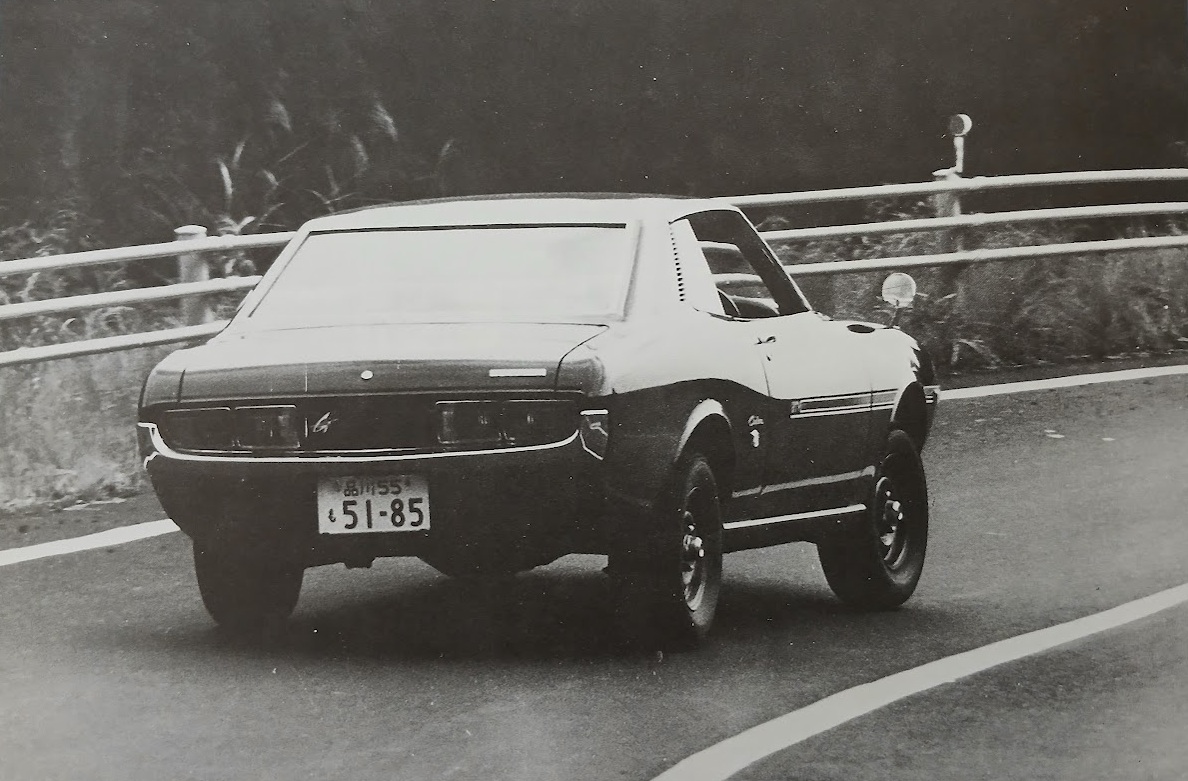

The biggest changes for these two new cars are in the suspension and tires. Toyota and Nissan have very different ideas when it comes to suspension. To achieve sporty handling, Toyota simply stiffens the conventionally designed suspension and splurges on tires, whereas Nissan focuses on the design of the suspension itself and uses tires of a normal grade. The suspension of the Celica GTV has been modified to be much stiffer than that of the GT, and the ride height is 10mm lower. Specifically, the front spring constants have been increased from 1.7kg/mm to 2.3kg/mm, and the rears from 1.7kg/mm to 2.2kg/mm, and the rear damping force has been strengthened by about 30-40%. The tires and wheels have also been changed from the GT’s 4.5J x 13 rims and 165HR-13 tires to a wider combination of 5J rims and 185HR-13 tires.

Meanwhile, the Bluebird U has also had its suspension significantly strengthened for the new 1600/1800 SSS/SSS-E models, but only those equipped with the 5-speed gearbox. The spring constant of the front springs has been increased from 1.5kg/mm to 2.1kg/mm, and the rear from 6.6kg/mm to 7.8kg/mm, and the damping force of the front and rear dampers has been increased (from 40kg extension/25kg compression front, 80kg/40kg rear, to 45kg/28kg and 66kg/42kg). This strengthened suspension has always been standard for export models. Another important change is that the wheels for all models (except the van) have been changed from 13 inches to 4.5J x 14, again using the standard equipment from the export hardtop.

The cars are also evenly matched in terms of price, with the Celica at 863,000 yen and the Bluebird at 864,000 yen. The GTV’s equipment is slightly simplified compared to the GT; its radio is AM only, and it does not have power windows or hubcaps, but it does have an oil temperature gauge, plus the wide rims and 70-series tires mentioned above. It is also 12,000 yen cheaper than the GT, so the trade-off will be welcomed by those who are serious about driving. The equipment of the 1600 SSS-E is the same as that of the 1600 SSS (5-speed, 814,000 yen) and is naturally simpler than the top-of-the-line 1800 SSS-E (964,000 yen), but the only things you lose in the 100,000 yen price difference are radial tires and a height adjustment mechanism for the driver’s seat.

Power Performance

As expected of a twin-cam engine, the Celica GTV’s 115ps/6400rpm 2T-G unit revs easily up to the redline of 7000rpm and above, allowing you to use the full rev range without any psychological stress. From the smooth idle of 800rpm to the redline, almost no vibration is transmitted to the body, and mechanical noise is kept exceptionally low for a DOHC engine.

The GTV’s top speed at Yatabe was 175.4km/h (the average over a 1km straight section), reached at 5850rpm in fifth gear. As mentioned, an oil temperature gauge is standard equipment, which is reassuring when cruising at high speeds. In 100km/h cruising on the highway, the oil temperature remained completely normal, and it rose to 110°C only when we maintained top speed for five or six consecutive laps around Yatabe, and during 30 minutes of continuous hill climbing, when we maintained 5000 to 6500rpm in second and third gear.

The gear spacing of the 5-speed gearbox is appropriate for the car’s power and weight. If you rev the engine to 7000rpm in first, second, and third gear, you can reach 51, 91, and 132km/h, respectively. Even in fourth gear, you can reach 172km/h (6600rpm), which is proof that the power is more than sufficient. On the other hand, this engine is also tenacious at low and medium speeds, and the overdrive fifth gear can be used at speeds below 60km/h if desired. Of course, the purpose of fifth is to be an economical cruising gear for driving on the highway at 100km/h or more. For example, 100km/h equates to 3800rpm in fourth gear, but in fifth gear it drops to 3300rpm, and the noise level becomes even quieter. There is no change in the transmission noise between fourth and fifth gear.

The shift pattern is the same as in the Fiat 124, with fifth gear located to the upper right, and you cannot shift into the reverse gate below that without lifting the lever, so there are no worries about making mistakes. The shift action is sure and light, with a relatively short throw and a pleasant feel.

What was a little disappointing about this car was its acceleration performance. The best 0-400m time was 17.5 seconds, and 0-1000m took 32.3 seconds, which was far behind the 16.8 seconds and 32.0 seconds of the Celica GT we tested last year, and in overtaking acceleration, the gap was even worse. On the other hand, the top speeds of 176.8km/h for the GT and 175.4km/h for the GTV were pretty much the same, so we don’t think that our GTV’s engine was particularly out of tune.

The most likely explanation for this is that, although the specs for this year’s GTV and last year’s GT are the same at 115ps, the current car’s engine has a much leaner carburetor setting than the 1971 model due to exhaust regulations, and we suspect that the accelerator pump’s output has been particularly restricted. In this case, there is a tendency for the engine to keep running even after the ignition is turned off, a condition known as “dieseling,” and we experienced this several times during this test, especially just after high-speed driving.

The output of the fuel-injected 1600 SSS-E is also 115ps (at 6200rpm), which is 10ps more than the carbureted twin-SU 1600 SSS, but this does not seem to make a noticeable difference in performance. Rather, the advantage of the fuel injection is its reliability in cold starting and the adjustment-free nature that keeps the engine running smoothly under all driving conditions.

In terms of performance, most of what we said when we tested the 1800 SSS-E also applies to the smaller-displacement 1600 SSS-E. As we have often noted, Nissan’s SOHC L-series unit is a bit rough by modern standards, has a high noise level, and is by no means free-revving. The sharp intake roar, fan noise, and valve gear noise become even louder during acceleration. The 1600 SSS-E camshaft has a valve lift of 10.9mm (the twin-SU 1600 SSS is 10.5mm) and an overlap of 38° (30°), making it the wildest of all the Bluebird U models, and generally speaking, the noise level is higher than that of the conventional SSS. It is relatively quiet up to 100km/h (about 3300rpm in fifth gear). The rev counter’s yellow zone is from 6500-7000rpm, and the red zone is 7000-8000rpm, but the psychologically tolerable rev limit is much lower, around 5500rpm. Fortunately, this engine has good low and mid-range torque characteristics, so you can avoid revving it above 5000rpm and still drive at quite a fast pace.

The 5-speed gearbox with Porsche-type servo synchro that is fitted to the 1600 SSS-E is the same unit used in the Skyline and Laurel. The final drive has been shortened to 4.38 (from 4.11 in the 4-speed model), with close ratios in the top three gears, and as is typical of Porsche-synchro gearboxes, the shift lever is extremely light in operation. If you push the engine to 7000rpm in each gear (the effective maximum), you can reach 56, 91, and 146km/h in first, second, and third gears. In direct fourth gear, it achieved 172km/h, exactly the same as the Celica GTV, at 6300rpm, 400rpm lower. The top speed in fifth was 172.4km/h (5450rpm) averaged over a 1km straight line. As usual, the speedometer was wildly inaccurate, indicating 191km/h at that speed. The best 0-400m acceleration time was 17.5 seconds, achieved by shifting up at 6500rpm. Stretching the upshifts to 7000rpm slowed the time to 17.6 seconds, so there is no point in revving it that high.

Comparing the two cars in terms of power performance, the GTV has a natural advantage with its slightly superior power-to-weight ratio and slightly smaller frontal area, so it is no surprise that it comes out on top in both top speed and acceleration. The Celica’s engine also revs more easily up to high speeds. On the other hand, the Bluebird excels in top gear flexibility, and its top gear acceleration from 40km/h to 120km/h is slightly better than the Celica GTV. The Celica’s DOHC engine has a momentary flat spot in the torque curve around 3000-4000rpm where the revs rise more slowly, whereas the 1600 SSS-E’s fuel injection engine’s torque curve is broad, and the top gear range is wider, so you can choose a more relaxed driving style if you want to.

Fuel Economy

In constant speed fuel economy tests conducted at Yatabe, contrary to expectations, the Celica with its twin double-choke Solex carburetors performed better than the Bosch fuel-injected Bluebird at both 60km/h and 100km/h. The cars’ gearing was almost the same, with fifth gear at 30.4km/h per 1000rpm for both, and fourth gear at 26.2km/h (Bluebird) and 27.3km/h (Celica) per 1000rpm. In this case, the Celica’s better power-to-weight ratio must have had an effect.

However, in a practical fuel economy test of about 600km on public roads, driving in a two-car convoy, the Bluebird was better in every section, with an overall average of 9.1km/l for the Bluebird and 8.4km/l for the Celica (after correcting for odometer error). For example, on an 80km drive from Yatabe back to Tokyo on a typically congested national highway, the average fuel consumption over a three-hour period was 9.7km/l for the Celica and 10.4km/l for the Bluebird. The Bluebird’s better fuel economy may be due to the fuel injection feature that shuts off the fuel when the throttle is closed. Both cars require high octane fuel (the GTV is also available in a regular fuel version with a lower compression ratio). The Celica’s fuel tank has been moved from under the trunk floor to behind the rear seats, for added safety in the event of a rear collision, but the 50-liter capacity remains the same. The Bluebird’s holds 55 liters.

Handling, Ride Comfort, and Brakes

With a significantly stiffened suspension, generously sized Bridgestone Radial RD-102 185/70HR-13 tires, and a variable steering ratio (18.0:1-20.5:1), the Celica GTV’s roadholding and maneuverability are far superior to the conventional Celica GT. First of all, the steering response has become much more reassuring, and it now follows even the slightest steering input at high speeds. The increase in steering force is very slight and still within an appropriate range. The degree of understeer, which was a little too strong in the GT, is just right in the GTV for the preferences of fast drivers. In uphill bends at medium speeds (80-90km/h), the power in third gear at full throttle is well balanced with the tires’ grip on the road, allowing cornering in a stable posture. As expected, the grip of the fat tires is strong, and there is much less body roll compared to the GT, so the inside rear wheel does not lift and spin even when full power is applied in tight, second-gear corners. The fact that the tire grip exceeds the engine power is also evidenced by the fact that there is almost no change in cornering attitude when the throttle is released mid-corner. The front wheels’ maximum turning angle is decreased slightly due to the wider tires, so the turning circle has increased from 4.8m for the Celica GT to 5.2m for the GTV.

The GTV’s ride is generally harder than the GT’s, and at low speeds, it feels as rough as an Alfa 1750, but at high speeds it becomes flat and comfortable. It is clear that the seats, with their good shape and firmness, contribute greatly to ride comfort. The Celica has recently been redesigned to add sound- and vibration-proofing materials to the dash and floor panels. Perhaps because of this, despite the wide radials, road noise is well suppressed, and vibrations from the suspension are well muted.

The brakes’ strength is appropriate for the power performance. The servo assistance is strong, and 0.5g braking can be achieved from 100km/h with just 15kg of pedal force. Nose dive during sudden braking, which was excessive in the GT, has been significantly reduced in the GTV with its firmer suspension. In the 0-100-0 fade test, the pedal force started at 15kg and gradually increased, reaching 29kg on the tenth stop, but this is still within the normal range.

As for the Bluebird U 1600 SSS-E, we were impressed by the overwhelming improvement in maneuverability compared to the 1800 SSS-E we tested last year. That 1800 SSS-E was fitted with Bridgestone Radial 20 165SR-13 tires, but the 1600 SSS-E we tested this time had much better cornering power and roadholding on its ordinary bias-ply Toyo E-31 6.45S-14 tires. The understeer was still strong, but it was no longer excessive, and even when we lifted off the throttle in mid-corner, the tendency for the front end to cut inwards (which actually only weakened the understeer) was much less pronounced. When we applied full power in third gear on an uphill bend that could be taken at 80-90km/h, the initial understeer gradually changed into well-controlled power oversteer, and the car’s posture became more stable. This allows the driver to slightly return the steering angle, which means the cornering speed is not sacrificed by the scrubbing resistance of the front wheels, and the car can exit smoothly at high speeds.

However, when we conducted a slalom test at 80-90km/h, weaving through pylons lined up at 30m intervals at Yatabe, the limitations of the Bluebird’s narrow bias-ply tires were revealed. When the throttle was closed to eliminate the excessive understeer, the tail swung out, and the yaw angle gradually increased with each cone we passed, making it difficult to maintain control. The Celica GTV’s grip was much stronger in the slalom, and it was able to weave through the pylons in a straighter line. However, the slalom test is extremely harsh, and it would be impossible to re-create these conditions on public roads.

In this comparative test, the Celica GTV won out in terms of handling, but if you were to ask us which car is easier for the average driver to handle, the answer might be the 1600 SSS-E, because it is easier to make its tail slide with throttle work. The Celica GTV has exceptionally good tire grip for a normal production car, but this makes it difficult to grasp its cornering limits, and once you exceed them, both the front and rear ends tend to slide at the same time.

Returning to the Bluebird U, we would like to see what kind of results would come from combining the high level of maneuverability on bias-plies with the grip of a good set of radial tires. The specified standard pressure for the bias-plies is 1.6kg/1.6kg, but we always ran them at 1.9kg/1.9kg and obtained good maneuverability. However, road joints and other impacts caused loud clunks and thumps, and it seems that more work is needed to block out road noise. We didn’t feel this so much with the 1800 SSS-E tested previously, but with the 1600 SSS-E, there was always a sense of heavy unsprung masses moving under the car, which we could feel as vibrations through the floor. Although our test car had less than 2,000km on the odometer, it felt like it had already been driven much longer than that.

The brakes have also been redesigned since last year’s 1800 SSS-E test, with the pads now being the fade-resistant S21B type, and the vacuum servo has changed from a 4.5-inch to a 6-inch diameter. However, at the same time, the pedal ratio was reduced from 5.0 to 4.2, which seems to have offset the reduction in pedal force. The pedal force was already light, so this is no problem, and what has improved is that the pedal stroke, which was previously excessive, has finally become appropriate. Resistance to fade is also sufficient, and in the 0-100-0 test, the initial pedal force of 18kg actually decreased until the third stop (indicating that the pads exert their maximum friction when they are somewhat warm), and then gradually increased to 25kg on the tenth stop. While its effectiveness was judged to be very good, the handbrake is still an under-dash umbrella handle type, which is inconvenient to use.

Interior and Equipment

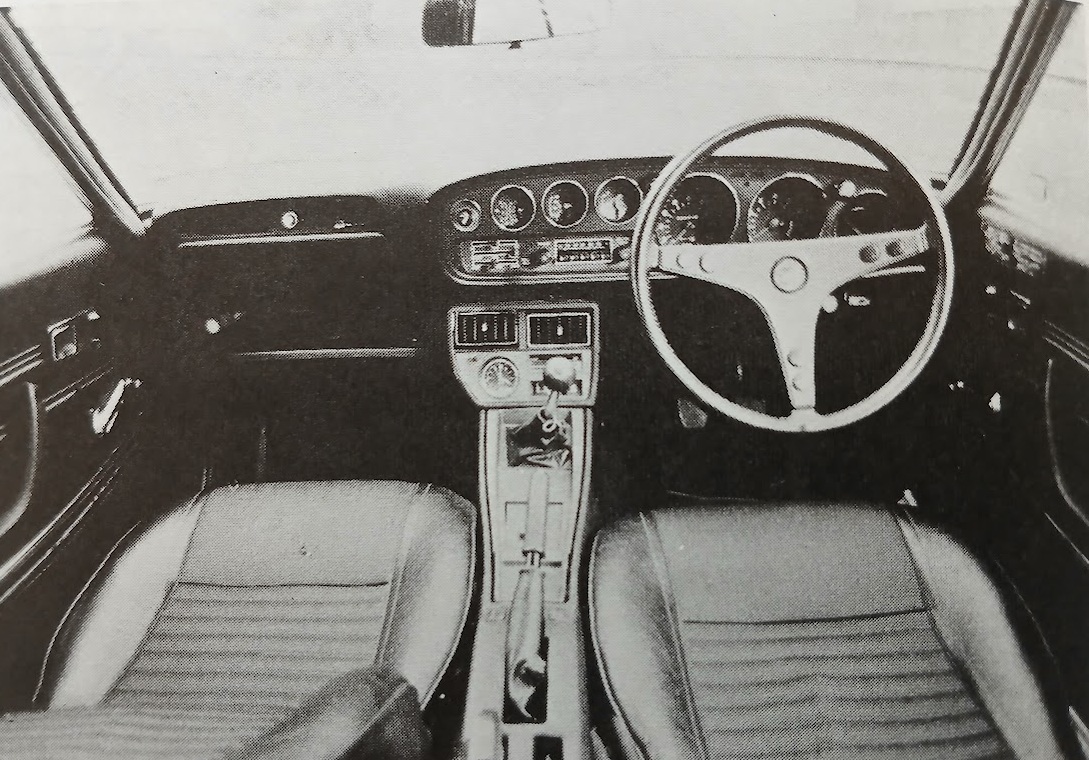

The interior atmosphere of these two cars is a study in contrasts. The Bluebird has beige trim and houndstooth tricot cloth seats, giving it a bright, sedan-like feel (and making it seem roomier than it actually is), while the Celica has a low, sports car-like seating position with all-black surroundings, including the knitted leather seats. In fact, the cars’ interior dimensions are quite similar, and if you compare the specs, the Bluebird’s is slightly longer front-to-rear, while the Celica’s is slightly wider.

Most of our drivers preferred the Celica’s driving position. The reason is that the Bluebird has abandoned its traditional high-waisted seats for the U series and adopted a lower seating position, resulting in a relatively high dashboard and steering wheel (only the 1800 has a height-adjustable seat). The Bluebird’s seats are generally well-shaped, but some minor points that bothered us were the narrowness of the bolsters on the cushion and backrest, which puts pressure on both sides, and the forward-protruding headrest that puts unnatural pressure on the back of the head. If anything, these seats are more comfortable to sit in than to drive in. The beige houndstooth upholstery looks a little cheap, but one big advantage of cloth upholstery is that it reduces sweating in the summer. On the other hand, the Celica’s seats have thin cushions but excellent shaping and generous dimensions, and the relative positions of the steering wheel and other controls allow you to assume a very natural driving position with your arms and legs stretched out comfortably.

Recent Japanese cars, as if by omission, have started to feature styling with unnecessarily wide rear quarter panels and steeply slanted rear windows. These result in extremely poor visibility to the rear and over the shoulders, a drawback shared by both cars. Of the two, this is especially true in the Bluebird, where the rear side windows are narrowed by the rear quarters (which are also extremely thick at the bottom), creating wide blind spots, and the glass area decreases towards the rear. Furthermore, the rear window is too steeply slanted, which tends to distort the image in the rearview mirror. Compared to the bright and airy interior of the Fiat 124 Coupe that accompanied us on this test, which had almost no blind spots, the difference was stark.

This styling has similar effects on the feeling of roominess in the rear seats. The wide blind spots and large front headrests narrow the rear passengers’ field of vision, and the rear window that stretches up all the way over their heads means that direct sunlight beams onto their backs, making the passengers in both cars feel claustrophobic. The brightly upholstered Bluebird is at least slightly better in this regard. The rear seat dimensions of the two cars are not that different, but a person about 178cm tall will hit their head on the hard rear window frame in the Bluebird, while the Celica has a cushion that is lowered, giving rear passengers more headroom. The Celica’s cushions are set into deep pockets, so only two people can ride comfortably, while the Bluebird’s seats are flat, so three people can ride in the rear. If the front seats are slid all the way back in either car, the rear passengers’ knees will hit the backrest.

Front seat belts are standard in both cars, but while the Bluebird has two-point seat belts, the Celica has three-point belts, which is more sensible in a sports car. However, they are uncomfortable as the retractor’s winding spring constantly tightens around the abdomen (the Bluebird only offers retractors on the 1800).

Both cars’ dash panels are luxuriously equipped with a wide array of gauges, including a tachometer, fuel gauge, water temperature gauge, oil pressure gauge, and a clock, and the Celica also has a current gauge and an oil temperature gauge. There are no particular problems with visibility of the gauges, day or night. The Celica’s instruments are visually more attractive, but the Bluebird’s light switch is superior in terms of function. A pull switch on the bottom right of the dash simply switches them on and off, and by moving the indicator stalk back and forth, the parking lights, low beams, high beams, and passing flasher can be conveniently controlled with your fingertips while still holding the steering wheel. By contrast, the Celica’s light and wiper switches are still on the dash under the deep hood of the instrument panel, requiring you to reach behind the steering wheel to get to them, which is difficult even if your seat belt is not fastened. One saving grace is that the knobs for the main switches in the Celica are internally illuminated (the brightness can be adjusted along with the gauges), so they are easy to find even at night.

Both steering wheels have leather grips (the Celica’s is covered in real leather, while the Bluebird’s one-piece molded vinyl rim only appears to be). As mentioned above, the position of the steering wheel in the Bluebird is too high and its diameter is a little too large. The Celica’s is better in both respects. The Bluebird’s horn button is in the center pad, but it would be better to have buttons in the spokes so the horn can be sounded while holding the rim, like in the Celica. Also, both cars are equipped with a locking steering column as standard, but the Celica has a safer two-step operation where the key cannot be removed until the lock button is pressed. The Bluebird’s under-dash handbrake would be easier to use if it was moved to the center tunnel, at least in the hardtop.

Other small improvements include the addition of a speed warning device in the Celica that can be set to chime when the car exceeds 100km/h (110km/h on our test car), and is not as annoying as a conventional buzzer. The GTV lacks the power windows of the Celica GT, but its manual windows are probably better for quick operation and, moreover, reliability. Both the GTV and 1600 SSS-E come with a standard AM radio, but the top-of-the-line versions of both cars have upgraded sound systems, with an AM/FM radio in the Celica GT and a push-button AM radio with cassette player as standard in the Bluebird 1800 SSS-E.

These days, it seems that the more recent the design year of a Japanese car, the better its ventilation system is, and these two cars are at a high level in that respect. First of all, both have vents on either end of the dash that direct fresh air at face level, and their consoles have a forced ventilator that is linked to the heater blower. The vents on the dash effectively draw in outside air even when the windows are closed and at speeds under 50km/h, and the console vents blow out a fairly strong wind even with the fan on the lowest setting. Of course, it is easy to create the ideal condition of a cool face and warm feet in winter. Another plus is that thermal wires for defogging the rear windows are standard on both.

The Bluebird has more interior storage space for small items. Both cars have average-size glove boxes (and are lockable), and the Celica has an undertray on the left side of the dash plus a shallow coin tray in the console, while the Bluebird has undertrays on both sides, a console storage compartment, and a deep box with a lid that doubles as a center armrest.

There is almost no difference in trunk space; both cars have the fuel tank placed behind the rear seats for safety reasons, so their trunks are short front-to-back. As is typical of short-deck-styled cars, the trunk lid is small and the opening is high in both, making it difficult to load and unload heavy luggage. The Celica previously had the fuel tank under the floor and the spare tire stored upright, which gave it a lot of usable space, but that is no longer the case with the new fuel tank placement and the spare tire buried under the floor.

There is a big difference in the quality of the tools provided. Toyota has always provided a good set of tools, including an adjustable spanner, a six-prong spanner, and two screwdrivers, regardless of the class of the car, but the Bluebird’s meager set doesn’t even include a plug wrench.

In conclusion, these cars are comparable in terms of power performance, and they both have high levels of maneuverability. They are both fun to drive, which is a rarity for domestic cars in this class these days. The Celica GTV is a step ahead in terms of handling, but this is largely due to the 5J rims and 185/70HR-13 radial tires. If the Bluebird were fitted with wider tires of the same type, the competition would be even more interesting. One final point is that while past Nissans were far inferior to Toyota in terms of interior finish and equipment, this gap has narrowed significantly since the Bluebird U was introduced.

Postscript: Story Photos