Nissan Violet Hardtop 1600SSS-E (1973)

Publication: Car Graphic

Format: Road Test

Date: April 1973

Author: “C/G Test Group” (uncredited)

Summary: Bluebird 510 in new clothes. Equipped with electronic fuel injection. Engine improved but still rough and noisy when revved up. Excellent 5-speed gearbox. A bit high geared overall. Handling is on the dull side. Nice, luxurious cabin. Brakes prone to fade.

Road testing the Violet Hardtop 1600SSS-EL

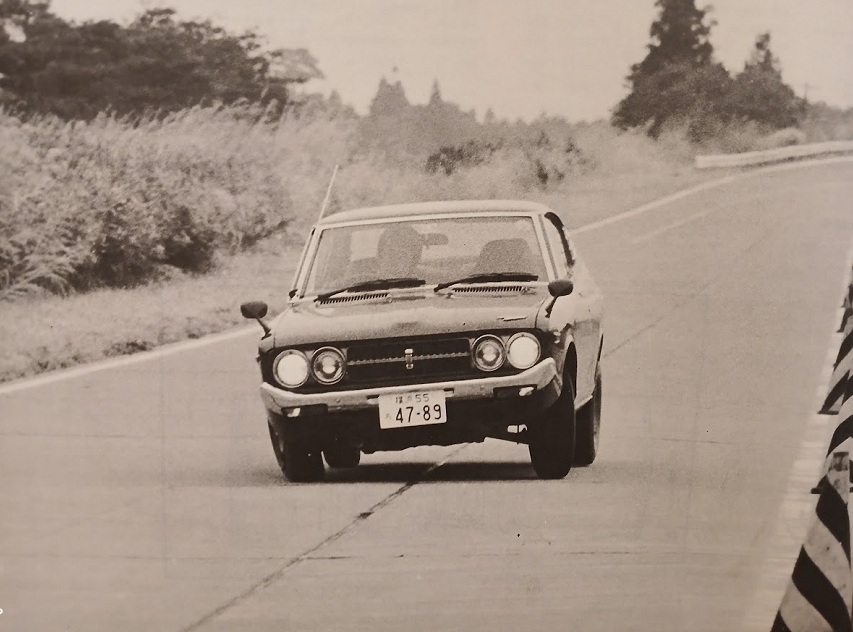

Nissan’s new 1.5-liter Violet series was announced in January, and we featured an overview and road impression in last month’s issue, but this time we went to the Yatabe test course to conduct a full test of the car’s top speed, acceleration, and other performance characteristics. The test car is the same one we used last time, the highest-end and highest-performance version in the series, the hardtop 1600SSS-E (840,000 yen for delivery in Tokyo).

The Violet’s body design matches current trends in domestic passenger cars, with an abundance of curves and a sculpted interior that seem almost unnecessary, but the majority of the engine, transmission, and chassis components are inherited from the old 510-type Bluebird (production of which ended at the end of last year), and shared with the current Bluebird U (610), so it is essentially an old car with a new body, so to speak. In that sense, it lacks freshness, similar to the Mitsubishi Lancer we tested at the same time. However, most new models these days are born with this kind of background, and while there is nothing groundbreaking about them, we can expect more refinement than in the past in details such as chassis tuning, soundproofing and vibration-proofing, and interior layout. For car manufacturers, this is also a safer, lower-risk way of developing new models.

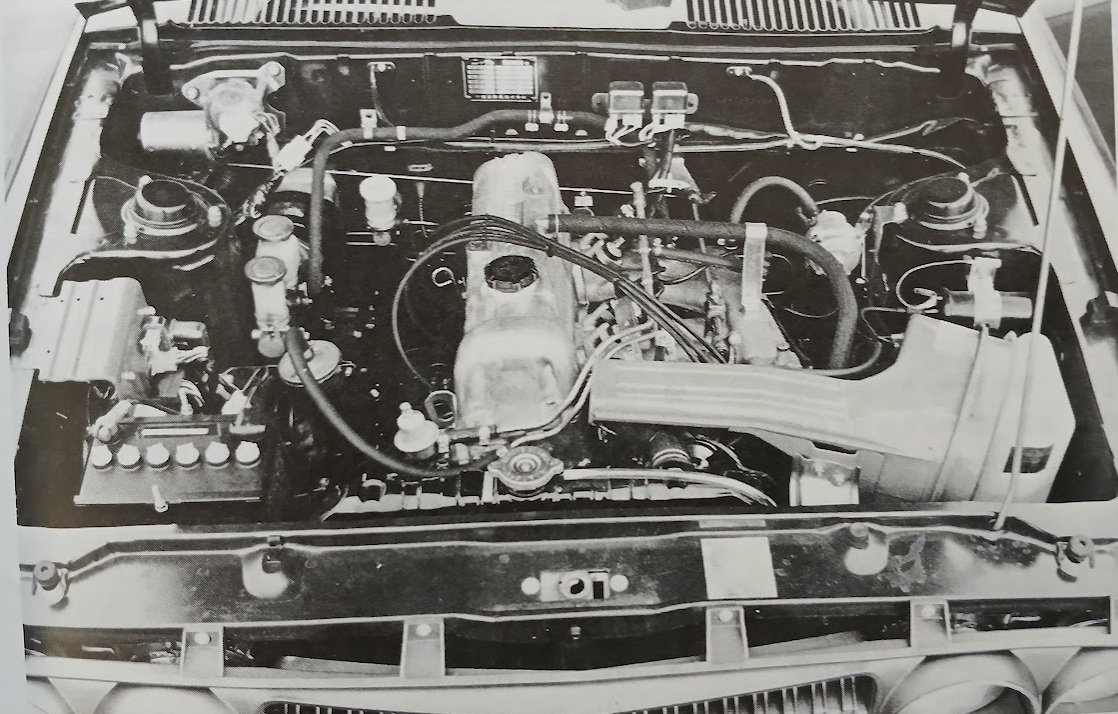

In the case of the Violet Hardtop 1600SSS-E, the engine is an L16 type SOHC four-cylinder with Bosch electronically controlled fuel injection, which is nearly identical to that used in the Bluebird U 1600SSS-E, and the suspension is also borrowed from the Bluebird U, with MacPherson struts and coil springs in the front, and semi-trailing arms with coil springs in the rear. Only the standard 5-speed gearbox was newly designed for this model. All Violet models (two- and four-door sedans and hardtops) except for the sporty SSS series have a rigid rear axle suspended by semi-elliptical leaf springs, which is actually the biggest difference from the old 510, and we plan to cover that version in a test drive report soon.

The 1595cc four-cylinder engine has the same power specifications as the Bluebird U 1600SSS-E, with a maximum output of 115ps/6200rpm and a maximum torque of 14.6kgm/4400rpm, but the compression ratio is 0.5 lower at 9.0, making it possible to use regular gasoline. Thanks to the electronic fuel injection, which automatically determines the mixture according to the ambient temperature, cooling water temperature, manifold vacuum, etc., cold starts are extremely easy, and even on cold early mornings when the temperature is around freezing, it wakes up obediently with just a moment of cranking, and starts its rough idle at around 700rpm. However, the engine does not warm up easily, and after waiting about four minutes with the throttle gently depressed and the engine at about 2000rpm, the needle on the water temperature gauge finally starts to move. On the other hand, there is almost no jerking even when you start driving immediately after start-up, in which case it is fully warmed up in about three minutes.

Nissan’s L-series engine has been criticized for being particularly bad among the domestic manufacturers’ generally rough four-cylinder units, but when combined with the Violet body, it is greatly improved in this respect. At low and medium speeds, it can be now said that its quietness and smoothness are at normal levels. This is probably the result of repeated improvements to the engine itself, as well as the attention paid to soundproofing and vibration-proofing of the engine mounts, firewall, and floor. However, at higher engine speeds, it remains as noisy and rough as ever, and this becomes clear at 4000rpm and above, and even gets psychologically tiresome once it exceeds 5000rpm. The rev counter is scaled up to 8000rpm, with the yellow zone starting from 6500rpm and red from 7000rpm, but the practical limit is 6000rpm at most. The high gearing, for a 1.6-liter practical car, gives more than enough practical performance if you only use up to 5000rpm in each gear, which is a big relief. The engine pulls easily to 7000rpm in the lower three gears, where the maximum speeds are 53km/h in first gear, 90km/h in second, and 141km/h in third. Therefore, even if the driver keeps the revs limited to 5000rpm, it is still possible to reach 38km/h in first gear, 64km/h in second gear, and 100km/h in third gear, so there is no problem maintaining a fast pace and leading the flow of traffic.

Compared to the premium-fuel 1.6-liter fuel injected unit in the Bluebird U, the Violet’s regular-fuel unit seemed to lack a bit of punch at high speeds, and this was evident by the fact that, while the Violet’s acceleration times were 0.2 seconds faster than the U for 0-50m, and 0.1 seconds faster from 0-100m, the cars were tied for 0-200m, and the Violet fell 0.1 second behind from 0-400m, and 0.4 seconds behind from 0-1000m. The overall gearing for both is almost the same, so the Violet, which is 20kg lighter, has an advantage at the start, but the difference in power at the top end must have become apparent when pushing each gear to the limit before upshifting. The Violet’s top speed in the flying kilometer was also significantly lower at 165.1km/h compared to the U’s 172.4km/h, and while the U revved to 6300rpm and reached 172km/h in direct fourth gear, the Violet revved to 6150rpm. The test car’s speedometer was surprisingly lenient, passing the 180km/h mark long before it reached its top speed in fourth gear, and by the time it reached its top speed in fifth, the needle was wandering off the scale.

The 5-speed gearbox that is paired with this engine is a new design for the Violet, and is standard on the SSS-E. This can also be selected an option for the SSS with twin SU carburetors. The ratios are 3.382 / 2.013 / 1.312 / 1.000 / 0.854, which are slightly wider than the 3.321 / 2.077 / 1.308 / 1.000 / 0.864 of the U, but combined with the engine’s flat torque characteristics, you don’t actually need five gears. In particular, the top three gears are close to each other, so when driving on normal public roads, you may even wonder which gear to use. Even if you decide to be lazy and just shift from first to third to fifth, it still runs quite well.

The second to fifth gears are arranged in an H-shape, with first gear to the left and down, a difficult-looking shift pattern found in rear-engined Porsches up to the 2.2 liter 911, and in the current VW-Porsche 914. In reality, first gear is used only for starting from rest, and from one point of view, it can be said to be convenient because the fifth gear can be used frequently in the city. To prevent inexperienced drivers from shifting to the left and up into reverse instead of first by mistake, the gate on the left requires the driver to push the lever against a strong spring, and a warning buzzer sounds when the gear lever is put into reverse. Abandoning the tradition of the Bluebird SSS, the gearbox uses a normal balk-ring synchro instead of the former Porsche type, but its capacity is sufficient for the 115ps, and the synchro could not be beaten during the acceleration tests. The lever movement is not too large, and the feel is moderate and pleasant. The gear change on the test car was a bit stiff and heavy, but this was probably because it was still practically a brand-new car.

The handling is typical of Nissan cars, heavy and stable, but generally dull and sluggish. Still, if you switch from the old 510, you will feel that the steering response has become a bit more precise. In the past, no matter how much you tried to finesse the steering wheel, the car would not turn in smoothly, and there was excessive understeer (partly due to the good grip of the rear wheels). This has been reduced in the Violet, so that the more you turn the wheel, the more the front end turns in. However, the steering wheel has nearly 10cm of play (including purely mechanical play) around the center position, so when driving straight, the car does not react to slight turns of the wheel to the left or right. However, if you continue to turn the wheel, it responds suddenly at the end of the play, which can be quite a surprise.

Although it works well enough, the Violet’s chassis feels much more sluggish than the Lancer we tested at the same time, and there was still strong understeer. After several turns in the pylon slalom, the amplitude of the front-end push became too large and the car could no longer turn, so we had to consciously close the throttle to tuck in the nose and nudge the tail out, just as if it were a front wheel drive car, in order to regain control. On the other hand, if you apply excess power and make the tail slide, the ultimate cornering limit is high, which is the strength of the independent rear suspension. But in that case, even with the quick steering, which has a relatively fast ratio and 3.3 turns lock to lock, you have to make quick corrections to stay on course, and the roll angles are large. This all looks very impressive from the outside, and the driver is putting in a lot of effort, but the result is slower than the Lancer, which seems to run more smoothly and gradually through the pylons.

The test car was fitted with optional radial tires (Bridgestone Super Speed Radial 20 165SR-13 in this case), and compared to the standard bias-ply tires (Bridgestone Super Speed 5 6.45SR-13-4PR) of the test car in last month’s issue, the ride was much firmer, but we couldn’t think of any particular advantages. At least, there won’t be much difference on dry roads. The wheels are 4.5J x 13 for the SSS series (4J x 13 for other Violets), which is supposed to improve handling compared to the 510, but rather than saying it has improved, it should again be said that it has become “normal.” It seems that Nissan’s engineers interpret the extremely insensitive handling “flavor” of the Cedric/Gloria, Fairlady Z, Skyline, Laurel, Bluebird U, and Sunny 1400, which is similar to steering a large ship, as being well suited to ordinary drivers.

In last month’s road impression, the Violet’s brakes held up even after a series of very tough downhill runs, but at Yatabe, it was too much for them to accelerate from a standstill to 100km/h, hit the brakes with the equivalent of 0-5g deceleration, and accelerate again as soon as we stopped. In our fade test called the “0-100-0,” in which this is repeated ten times, the brake pedal pressure increased sharply from around the fifth stop, a burning smell filled the interior, and white smoke billowed out from the wheel wells. By the tenth stop, the brake pedal pressure started to reduce again, but by then, the braking distances were hopelessly long. The amount of nose dive during sudden braking was very small.

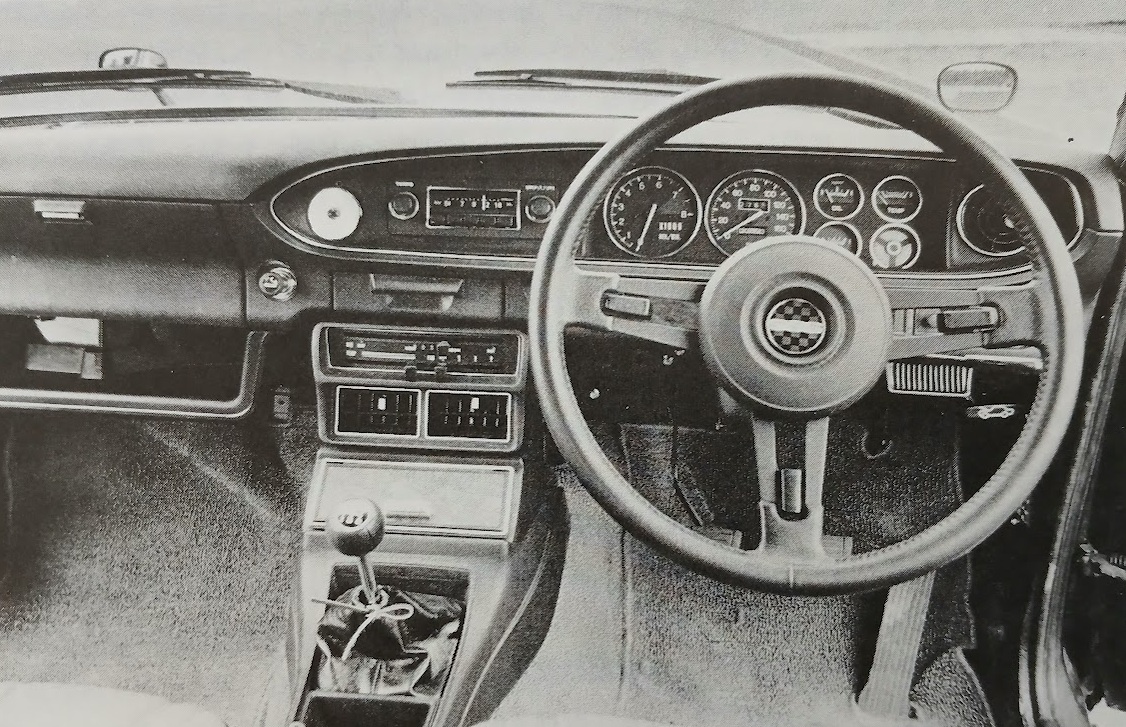

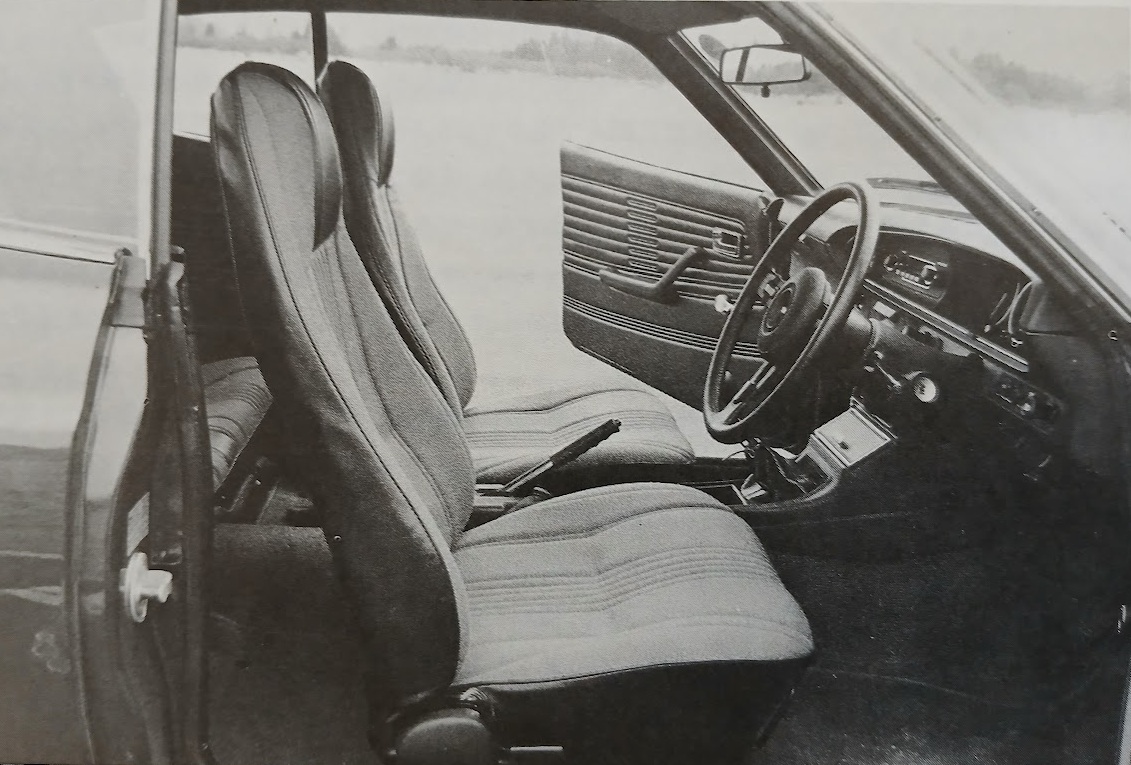

The interior is relatively straightforward for a recent Nissan car. The instrument panel is somewhat reminiscent of the Toyota Celica’s, and the six gauges, large and small, that are lined up on it are covered by a single sheet of non-reflective glass. It is much easier to use than the gloomy designs where each gauge seems to be hiding in the depths of a deep cave. The leather-rimmed steering wheel is also pleasing, but the overall feeling is somewhat cramped because the surrounding controls, scuttle, windowsills, and waistline are too high for the relatively low seating position, so you have to crane your neck like you’re sitting in a bathtub. This effect was very noticeable because the Lancer that accompanied us boasted a higher seat and a wider field of vision.

In terms of secondary controls, the heater/ventilation system is excellent. Not only can a large amount of cool air be brought in from the eyelet-shaped vents on both sides of the dash, but the heater can also be finely adjusted in three stages to balance the cool air at face level, making it very comfortable. The ram effect caused by the wind is not sensitive to changes in vehicle speed, so you don’t have to fiddle with the temperature control lever. For the light switch, you pull the knob on the bottom right of the dash one notch, and then use the lever on the steering column to switch between the parking lights and headlights, and to operate the high and low beams, etc. This is a convenient system, especially since the main switch is far away.

The fuel consumption rate was a middling 7.4km/l over the 500km test distance, including the tough testing at Yatabe. In crowded city streets, it averaged around 6.5-7km/l. The fuel consumption at a constant speed was also not very good, but in any case, it is unlikely to get any worse in such situations. In normal driving, unless you are driving extremely fast, you should be able to take advantage of the characteristics of the electronically controlled fuel injection, which cuts off the fuel supply when the throttle is closed, and once you get used to it, you should be able to drive quite economically.

After the test, our impression of the Violet remained in our minds only in a very vague form. It is a faithful successor to the Bluebird 510, a scaled-down version of the Bluebird U, and, in short, a modern Nissan compact car. So, if a current Nissan owner were to switch from their car into this one, they would probably think, “ah, I thought so,” and if it were someone’s very first time driving a car, they might come to understand that this is what a normal car is like. That may be what the designers of the Violet were aiming for.

Postscript: Story Photos