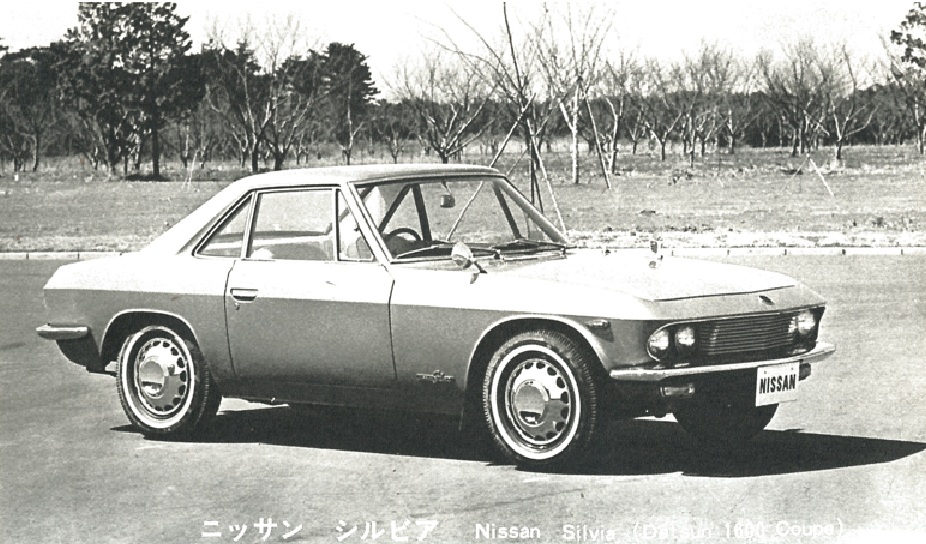

Nissan Silvia (1965)

Publication: Car Graphic

Format: Special Feature: “New Japanese Cars”

Date: May 1965

Author: Keiichiro Ichikawa

Introducing the Nissan Silvia

Nissan’s new Silvia is a two-seater coupe with a beautifully-proportioned body, and both the design and the finish are excellent. Leather surfaces, reminiscent of high-end British coachwork, are seen everywhere in the interior, psychologically expanding the interior space and making the work of driving more relaxing, a distinctive feature of this car. However, compared to custom bodies from Italy, it is still over-decorated.

Nissan Motors exhibited a beautiful semi-custom sports coupe based on the Fairlady 1500 at the Tokyo Motor Show last fall, and on April 1st it was released under the name Silvia (Silvia is a woman’s name that also appears in Greek mythology). The price is surprisingly high at 1.2 million yen for delivery to Tokyo, and the manufacturer’s intention is thought to be to initially produce around 100 units per month, with a semi-handmade build process to give them a semi-custom character.

The Silvia is basically derived from the Datsun Fairlady, and the chassis is the same except for minor improvements to accommodate the coupe body. The frame (the one from the old Bluebird 310, reinforced with an X-member) is also unchanged except for the tail being shortened due to fit the short rear overhang. The suspension is also unchanged with independent coil springs and unequal length wishbones at the front, and a rigid axle with leaf springs in the rear, but the front brakes are now Dunlop Mk II type discs (diameter 284mm), and as a result the track has been widened by 57mm to 1270mm only in the front. The wheels have also been enlarged from 13" to 14". The tires are 5.60-14.

The engine is basically the same OHV inline Four-cylinder as the Fairlady, but the bore has been enlarged and the stroke shortened from 80mm x 74mm to 87mm x 67mm, and the cylinder volume has been increased from 1488cc to 1595cc. At the same time, the shape of the intake manifold has been refined to reduce intake resistance, and the type of metal used for the large end of the connecting rods is now F770. The resulting compression ratio is now 9.0, and while still using two Hitachi SU-type carburetors, power output has increased from 80ps/5600rpm to 90ps/6000rpm, and the torque has increased from 12.0kgm/4000rpm to 13.5kgm/4000rpm.

What is most noteworthy about the Silvia is the power train behind the engine. The single-plate dry clutch with an outer diameter of 200mm has a diaphragm spring instead of a coil. Furthermore, the 4-speed transmission has full synchromesh of a servo type patented by Porsche in West Germany. The gear ratios, with the Fairlady’s in parentheses for reference, are 3.382 (3.515), 2.013 (2.140), 1.312 (1.328), and 1.000 (same), which are closer than the Fairlady. The final drive ratio has been reduced from 3.89 to 4.11 because the wheels are 1" larger, but 3.89 gears are still available as an option.

The sculpted beauty of this two-seater coupe is said by the manufacturer to be the work of Nissan Motors’ Modeling Department, but some foreign magazines have reported that it was clearly the work of Albrecht Goertz, a German designer based in New York, and it seems that this may be correct. In any case, the interior and exterior of the Silvia show a shape and finish that is in no way inferior to custom sports cars from Italy. The car weighs 980kg, 70kg more than the Fairlady, but the increased engine power, higher gearing, and reduced air resistance have improved the maximum speed to 165km/h and reduced the 0-400m time to 17.9 seconds.

The carefully prepared test car, fitted with Bridgestone racing tires, recorded a top speed of 178km/h at Yatabe, lapping the 5.5km course at an average speed of 174km/h. It also recorded a standing 0-400m acceleration time of 17.3 seconds, slightly better than the manufacturer’s published time, proving its true potential. As far as numbers go, this car is on par with, or sometimes even exceeds, the Sunbeam Alpine, MGB, Fiat 1600S, Porsche 356C, and Volvo P1800. Even if it’s not suitable for racing, it still ranks among the fastest and most luxurious Gran Turismos in its class in the world.

Road impressions

Now that I’m writing up the Silvia test report, I feel like I’ve understood the Silvia’s character. I drove it freely on crowded city streets, on the bumpy roads of Chiba and Ibaraki prefectures, and on the winding roads along the ridges of Hakone and Izu. I believe that roads are what change the performance and design of a car. When the Meishin Expressway was first built, it was like a joint test course for Japanese car manufacturers, and was particularly useful for research into high-speed driving. Today, the Meishin Expressway, with its new speed limit of 100km/h, is no longer useful. In other words, we have entered an era where the ability to drive “100mph” (161km/h) is the new standard. The Silvia, whose catalog data lists a top speed of 165km/h, demonstrated outstanding high-speed performance at just under 180km/h at the Yatabe High-Speed Proving Ground, where the design speed is 190km/h. Moreover, the Silvia had no problem navigating rough roads that the Fairlady 1500 would never be able to traverse gracefully.

Now, let me get into the main part of my test report, evaluating the Silvia as a “100 mph” car.

Easy-to-use servo type synchromesh

The Silvia’s most significant mechanical feature is its servo synchro gearbox. This is an excellent synchro mechanism that was patented by Porsche in West Germany and was installed in Nissan cars through a technical collaboration. Shifting up and down between the four forward gears can be done freely and quickly, and the shift action of the floor-mounted lever is so precise that I never once heard the gears clash. The short shift lever has a knob with a rather large grip on top. With no special technique, you can select gears at will at any speed from 0 to 100mph. I found myself using the lower gears, in particular, at least twice as often as usual. This is due to the ease of downshifting, and I found shifting from second gear to low gear and using engine braking to be a very effective way to reduce speed. If I had to say something negative to say, it would be that the location of the shift lever should be moved forward 20 or 30mm. I am 170cm tall, and had slid the driver’s seat to the rearmost position and tilted the backrest back one or two steps, but still felt that the shift lever should be a little further forward. As it is, I found my hand searching for the steering wheel between shifts. That said, the steering wheel and shifter can be held at arm’s length, and the legs can be almost fully extended to operate the pedals, allowing you to drive in a comfortable position. This is less tiring and is ideal for long-distance driving. The interior surfaces and seats are all finished in white vinyl leather, except for the black vinyl leather that covers the instrument panel. On the test car, it looked dirty. Certainly, if the owner doesn’t clean it at least once a month, the scuffs will become noticeable. I also would have preferred a headrest attached to the top of the seat’s backrest.

Impressions of the maximum speed, “178km/h”

When I tried driving at full throttle at the Yatabe High-Speed Proving Ground, the Silvia’s speedometer only went up to 180km/h, but as confirmed by Mr. C (from Nissan), who was in the passenger seat, and as I could clearly see, the needle was pointing to 178km/h. Incidentally, when I drove at full throttle around this 5.5km course, with the lap timed using two stopwatches, it completed the course in 1 minute 54 seconds flat. Converting this to 48.2m per second gives a result of 173.7km/h. In other words, the car drove around this course with its steep vertical banking at a average speed of 174km/h. So, it is natural that the maximum speed on the straights should reach 180km/h. Of course, at this speed, the tachometer was in the red zone, probably around 6700rpm.

In any case, the engine has good acceleration characteristics, and in first or second gear, with just light pressure on the accelerator pedal, the engine quickly reaches 7000rpm. The feeling is unmistakably that of an ultra-oversquare, high-speed type engine. If I had to score the Silvia’s driving performance at 170 or 180km/h, or 100 mph or more, I would give it at least 80 out of 100 points. Even though the suspension is soft on rough roads, there is no “float” at all, even when driving on freshly paved concrete roads at 100 mph or more. Rather, it seems to hunker down and feels extremely stable. This excellent high-speed stability was another reason why the average lap time at Yatabe could reach 174km/h.

From the sidelines at Yatabe, the sight of the test cars sprinting at speeds over 100 mph was truly spectacular. Something about the car’s appearance from a distance reminded me of a small Carrera. And the racing tires that were installed on the test day for safety reasons, and the black-painted wheels fitted with them, look perfect on this car. They give a more masculine and intense impression than the standard car with its white-ribbon tires and glittering wheel covers. In this form, it becomes a car with a tough, speedy style that hardly suits the name “Silvia.”

The Nardi wood-rimmed steering wheel with three aluminum spokes is not only stylish but enhances the sporty mood. However, it is a pity that the wooden shift lever knob, which had the same finish as the steering wheel, has been changed to a black rubber knob for the production model. I hope that the production technology to return to a wooden knob will be perfected soon.

There were a few disturbances in the car’s body when traveling at 100 mph, and the driver’s door frame developed a crack in the southeast corner of the course (the part of the course with the worst surface finish). The sash was wobbly afterwards. Of course, this was probably due to the fact that the car was a prototype production model (still being built at a rate of only 9 units per month). There was also some annoying wind noise. It must be particularly difficult to fit the windows precisely in a car that uses a lot of curved glass. The fender mirrors also cannot overcome wind resistance at speeds over 100mph, and naturally bend in the direction of the wind stream. If possible, I would like to see proper high-speed mirrors installed.

When continuously running the engine at high rpm, it was unsettling not to have an oil pressure gauge like in the Fairlady 1500. The speedometer and tachometer are installed in a very easy-to-read position, but while their design is stylish, the glass lenses reflect sunlight. The clock embedded between these two instruments should be replaced with an oil pressure gauge, and if I were to be even more greedy, I would like to see an oil cooler and oil temperature gauge fitted as well. If that were to happen, the Silvia would fit right into the sports car category, but since the manufacturer is marketing it as a luxury passenger car, I might be scolded for saying so. In any case, oil pressure and temperature are several times more important than fuel or a clock, so I would like them to be standard equipment, even on a high-speed touring car like this.

The Silvia’s acceleration response up to 100 mph is excellent, but when it gets to 170km/h or more, as demonstrated by the output curve, it is not surprising that the car does not have the same kind of punch as the Lotus Elan. Although this is unavoidable given the differences in the design principles, I wonder how difficult it would be to mount a 2000cc class twin-cam engine in the car. Perhaps we should look to the open-top Fairlady 1500 for something like that. For the Silvia, it might be better to equip it with a Borg-Warner automatic transmission and increase the engine displacement a little more. Those who want such improvements might naturally also ask for a power antenna, power windows, power steering, and power brakes.

In any case, it is fair to say that I have never driven a Japanese-made car that offered such stable driving performance at over 100 mph.

0-100km/h in exactly 10 seconds, 0-400m in 17.3 seconds!

Standing-start acceleration (measured by stopwatch and the speedometer) recorded an astonishing 0-100km/h time of just 10 seconds. Then, in two consecutive 0-400m runs, the times were 17.4 seconds and 17.3 seconds, both of which were a few tenths of a second faster than the manufacturer’s published catalog data. It was a fairly windy afternoon, so if there was no wind, it seems possible to achieve a time close to 17 seconds flat. It should be noted, though, that these times were all recorded with the cars on BS racing tires.

I was surprised at the good acceleration times, but what impressed me even more was the durability of the diaphragm spring clutch, which was newly adopted for this car. Even after dozens of abrupt standing starts (most of them at full throttle), there was no slip or seizure and full-throttle operation was stable.

After my last 0-400m run, I slowed down with engine braking and returned to the service station, and when I came to a stop and let the car idle, it showed no signs of being treated roughly, and when I switched off the ignition, it stopped smoothly without a trace of dieseling. And when I opened the hood, I was almost surprised to find an ordinary OHV engine with normally-tuned SU twin carburetors installed there. Seeing this, I felt that Nissan’s small engine deserves particular praise for being able to withstand such hardship.

Good at rough road driving

Driving on rough country roads is not an ideal condition for any sports car, but the Silvia is marketed as a luxury car, or rather as a full-fledged high-speed touring car like the Volvo P1800 or Porsche 911, and its soft suspension absorbs shocks very well, causing no resonance in the body.

The 170mm ground clearance is sufficient for the rough roads in Japan, and the fact that the fuel tank does not protrude from underneath the tail like the Fairlady 1500 makes it easier to drive. When I was driving at an average speed of 60km/h on the two-lane gravel road from Ushiku-cho to the Yatabe test course, we were followed by two sedans and a sports car, but I lost sight of them within two minutes. The Silvia’s handling and maneuverability when driving fast on rough roads are also satisfactory. The only thing is that the wheel covers are thin, and they were dented in a few places by stones that were kicked up. The material used needs to be reconsidered.

Some people say that the suspension of the Silvia should be made a little stiffer, but I am against it. The results of the cornering tests showed that the roll rate was not particularly small, but combined with the understeering characteristics, the car had good adhesion to the road surface, and even when driving at speeds of over 100 mph, the softness of the suspension was not noticeable. Rather, it was held down by the aerodynamic body style, making it very stable. These factors make the car particularly stable on rough roads, and I think that the current specifications are perfect for this car, demonstrating excellent road holding.

My own Silvia “order”

Finally, indulge me by allowing me share my personal opinion. I would like to imagine a Silvia exactly as I would like it to be.

First of all, the lack of a lock on the triangular window around the driver’s seat is worrisome. The current Fairlady 1500 also lacks a locking device, but my friend “H,” another test driver, actually managed to pry open the triangular window by hand. Considering the cases of theft and attempted theft, I would really like to see a push button locking device installed. Next, while the gauges are beautiful and elegantly designed for night driving with the lights on, the glass reflects light during the day and makes them hard to read. I would like to see a small hood or some other solution.

The glove box on the left side of the instrument panel has the opening mechanism as the Bluebird, and it is too shabby for a 1.2 million yen car. It should have a stronger hinge and a locking mechanism, since many people are in the habit of putting their vehicle registration certificate in there.

The heater switch levers on the lower right are too stiff to operate accurately, perhaps only in this sample car. I would like to be able to set each position more smoothly and to eliminate the noises when setting them. The rear quarter windows should be made to open and close on both sides like the Cedric to improve ventilation. This should greatly improve cabin ventilation.

It would be easier for tall people to use the shift lever if it were moved forward by 20 or 30mm. With the current arrangement, my elbow would hit the armrest box on the center tunnel. It would be better for the trip recorder to have a push-button to reset it to 0 like the Cedric, rather than using the slower manual return type.

In addition, a power antenna is an absolute necessity. This way, it can be tucked away when driving at high speed, and extended high when driving slowly in town to listen to the radio.

I would also like to see a mirror on the back of the sun visor like in the Cedric. I want to be able to straighten my tie in the car and not get flustered when I get out… I’m sure I’d often be driving this car in a suit if I were the owner. I’d also like to have a defroster on the rear window. It’s difficult to drive in a sporting manner when the rear window is fogged up. The view from the rearview mirror is also narrow. I would like a wider one, even if it is a little more curved.

There is a strange noise coming from the inside door handles, just like in the Bluebird. I’d like to see something done about it. I would prefer Knob-type door locks, too. The lock integrated with the handle is modern in appearance, but it can be opened accidentally and its operation is uncertain. I would like to see headrests, even if they are optional. I would also like to see a sliding roof developed soon. And ideally, even if it’s a little unconventional and ruins the dream-car image, I would like to see a 2+2 type sold commercially for a family of two adults and two children, even if it is in small quantities…

The horn is fine even on the highway, but it is too noisy in quiet towns because it does not have a separate “town and country” feature. I would like to have an auto-tuning radio. I think it is time for such car radios to be standard equipment. Finally, if Nissan were to add a Borg-Warner automatic, power windows, power steering, and power brakes, the Silvia would be a true high-speed touring car with a unique body style and performance that would not be embarrassing even it it was released on the world market. Although I have made a long list of selfish requests, I hope that the Silvia currently on the market will become an even more “complete” car over time.

In any case, the emergence of this type of car, with its strong custom-built feel, is a symbol of the level of technology achieved by today’s domestically produced cars, and there is significant value in its existence.

Postscript: Photo captions

The wide, chrome-plated wheel covers, which protrude from the car’s corners, seriously impede its maneuverability in tight turning situations. It would be better if the wheels were more functional, if not quite wire wheels.

The most beautiful part of the car is the shape of the roof where it extends to the quarter panels, rear fenders, trunk, and tail. The quarter panels and fenders in particular are one continuous design, like a design from Pininfarina, and the metallic paint (currently only available in light green) makes them shine beautifully depending on the angle they are viewed from. Even from the car’s best angle, you can see the pointlessness of the protruding wheel covers. Starting from the engine, the exhaust is divided into the four outlets that blend gradually into two to avoid interference, then combine to a single pipe with only one muffler, and then diverge again into two tailpipes.

With its 11.1cm disc brakes on the front, the Silvia can stop in 13.5m from 50km/h. The amount of nose dive is normal, so the slightly downward-sloping design is emphasized in photos of the braking tests.

The cockpit is a stunning design that is not inferior to custom sports cars from Italy. The instruments, from left to right, are fuel, trip, speedometer (up to 180km/h) with odometer, tachometer (up to 7000rpm, with red zone over 6000rpm), and water temperature. The gauges themselves are the same as those on the Fairlady. However, the oil pressure and electrical current gauges from the Fairlady have been replaced with warning lights for some reason.

The semi-bucket driver’s seat can be adjusted 160mm forward and backward. The seat back can be tilted in seven steps, designed to allow the driver’s viewpoint to be adjusted according to height. To tilt the seat back, you pull the lever on the side and push it backwards, but to return it to its original position, you must push it forward firmly. Seat belts are standard equipment, and when not in use, they are automatically retracted by a spring. There is a storage compartment under the armrest of the center console, and an ashtray is located in front of it. The glove box on the dashboard can be locked. The angle of illumination of the map reading lights can be adjusted, and the brightness of the instrument panel lighting can be adjusted with a rheostat. The seats and upholstery are made of ivory-colored vinyl leather that is close to pure white, but this will likely get dirty easily. It would be nice if a color more similar to natural leather was available. If the curved glass side windows could be more effectively sealed with rubber and the B-pillar removed entirely, it would give an even more luxurious custom car-like feel.

The R-type engine looks the same as the Fairlady’s G-type, but the bore and stroke have been altered to give a displacement of 1595cc, and the inlet manifold has been redesigned to reduce intake resistance, increasing output to 90ps/6000rpm. The carburetors are Hitachi SU-type, and the compression ratio remains the same at 9.0. The metal on the big end of the connecting rod has also been strengthened, making it possible to operate continuously even at higher speeds.

In cornering with BS racing tires, the roll angle cannot be called minimal, but the tires hold the road very well. The steering balance is completely neutral.

With racing tires and the wheel covers removed, the Silvia’s body glittered in the light as it hurtled down the straight sections. At Yatabe, the car reached an average speed of 174km/h, but as it came down off the banking, it appeared to have momentarily reached 180km/h. The best recorded 0-400m time was 16.9 seconds, one second better than the manufacturer’s published time of 17.9 seconds.

What is amazing about the Silvia is that it is more resistant to unpaved roads than the Fairlady. This is largely due to the relatively soft springs, but in any case, it can be said that this car’s resistance to rough roads is among the best of any sports car in the world.