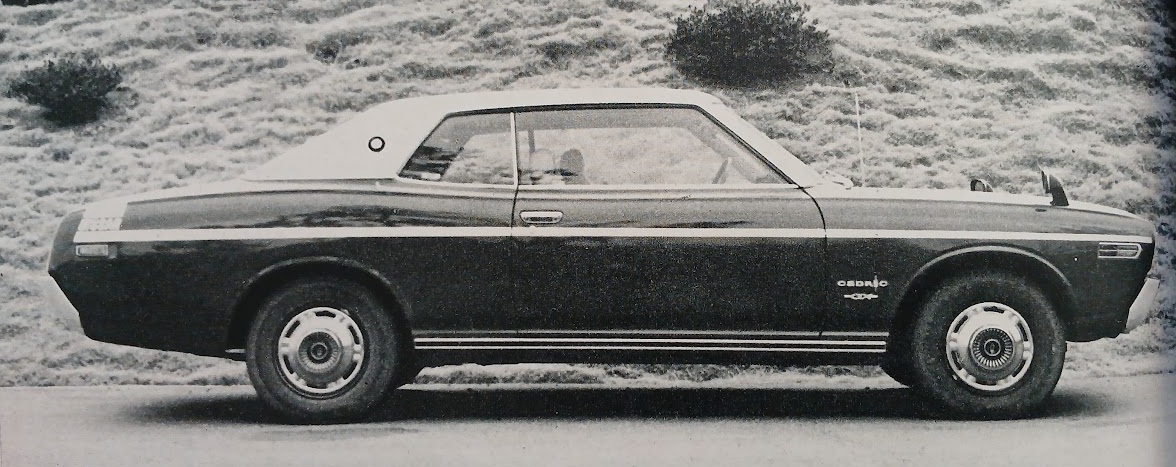

Nissan Cedric Hardtop GX vs Toyota Crown Hardtop Super Saloon (1971)

Publication: Car Graphic

Format: Group Test

Date: December 1971

Author: Shotaro Kobayashi

Comparison Test: Nissan Cedric Hardtop GX vs. Toyota Crown Hardtop Super Saloon

When one hears the names Crown or Cedric, the image that most readily comes to mind is a black company car gliding along at an unhurried pace with a senior executive in the rear seat–or else the internationally infamous “kamikaze” taxi. This not-entirely-flattering image was first shattered some four years ago with the introduction of the Owner Deluxe, marketed under the catchphrase “The White Crown.” It was then decisively overturned by the launch of the Hardtop in the autumn of 1968. With that, the Crown secured a firm foothold among affluent owner-drivers seeking a truly personal luxury car.

Looking at the 1970 model year as an example, of the total 80,938 Crowns registered, 18,469 were Hardtops, roughly one in every four. If one excludes company cars and taxis and considers only privately owned vehicles, the proportion of Crown Hardtops rises still further, to an estimated 40%.

Nissan, by contrast, had been less aggressive than Toyota in cultivating private-owner demand for the Cedric, no doubt in part because it already had a well-regarded 2-liter class contender, the Skyline 2000GT. However, with the Cedric’s latest model change, Nissan has finally taken the plunge and introduced a Hardtop.

The Cedric Hardtop (and the Gloria Hardtop, which is mechanically identical apart from exterior trim) is offered in four variants, while the Crown Hardtop comes in five. In addition, each is available in four transmission combinations: a 3-speed column-shift or 4-speed floor-shift manual, and a 3-speed floor- or column-shift automatic. For this test we selected the flagship models of each line: the Cedric Hardtop GX (K230HAMTK-G) and the Crown Hardtop Super Saloon (MS70-HG), both equipped with three-speed floor-shift automatic transmissions.

What buyers of this type of hardtop expect, first and foremost, is not outright performance but lavish equipment, generous comfort, and easy, relaxed drivability. In other words, the ideal is a moderately scaled-down “Japanese American car.” This was the reasoning behind our decision to compare the top-specification versions, complete with torque-converter automatics, power steering, and a full complement of accessories.

These two cars are aimed squarely at the same, clearly defined market, and because both are designed to fit just within the very limits of the 5-number compact-car class, there is little to choose between them in overall dimensions, weight, or output. Both are powered by six-cylinder SOHC engines with twin carburetors, mated to 3-speed automatics with planetary gearsets.

The most significant mechanical difference is structural: the Cedric employs a monocoque body, while the Crown is built around a robust perimeter-frame chassis. In practice, however, the additional underbody reinforcements required by the hardtop body style largely offset this theoretical advantage, and the Cedric (at 1360kg) ends up, contrary to expectations, 5kg heavier than the Crown.

In terms of engine output, the Cedric holds a slight edge, producing 130ps at 6000rpm (compression ratio 9.5, twin SU carburetors), compared with the Crown’s 115ps at 5800rpm (compression ratio 9.0, twin Aisan two-barrel carburetors). Accordingly, the power-to-weight figures stand at 10.47kg/ps for the Cedric versus 11.78kg/ps for the Crown, giving the Nissan a clear on-paper advantage.

Both automatic transmissions are of a very basic design, combining a torque converter with a 3-speed planetary gearbox. In addition to Drive, there are only manual lock positions for first and second gear; unlike some more-sophisticated foreign automatics, there is no sporty “S” range. (On the Crown Hardtop SL, however, an electronically controlled automatic transmission is available as a 30,000 yen option; this will be discussed later.)

The chassis layouts are entirely conventional. Both cars use double wishbones at the front and a live axle at the rear. The Cedric employs semi-elliptic leaf springs at the rear, while the Crown uses a four-link arrangement with a Panhard rod and coil springs. Front brakes on both are servo-assisted discs, and each is fitted with a pressure control valve to prevent premature rear-wheel lockup.

Both cars ride on 5J×14 wheels. Tire sizes are 6.95S-14-4PR on the Cedric (the test car was fitted with optional Dunlop SP68 175S-14 radials) and 6.95-14-4PR on the Crown (the test car had Toyo polyester-cord tires). The power steering systems differ in principle: on the Cedric the assist acts on the tie rods, while on the Crown it acts directly on the worm shaft in the steering gearbox. Both cars are equipped with collapsible steering columns.

Power Performance

The Cedric’s L-series six-cylinder engine has been improved by increasing the number of crankshaft balance weights from four to eight (this revised engine has been used in the Skyline and Fairlady Z since late last year). As a result, it now spins very smoothly and lightly from idle all the way to 6200rpm, where valve float begins, precisely coinciding with the start of the red zone.

The switch to a two-piece propeller shaft has also paid dividends: the driveline is virtually free of vibration at all speeds, and the car glides along quietly and smoothly. Automatic upshifts and downshifts are likewise extremely smooth. Under normal throttle in D range, the 1-2 upshift occurs at about 20km/h and the 2-3 upshift at around 48km/h, corresponding to engine speeds of roughly 2200rpm and 2800rpm, respectively. Under full throttle, upshifts occur at 5000rpm, which corresponds to about 50km/h in first gear and 90km/h in second.

That said, the relative lack of power cannot be concealed. It is keenly felt during acceleration from a standstill up to around 40km/h. On the other hand, once the car has gathered speed–albeit only in the moderate speed range realistically attainable in urban driving–it moves along with a fair lightness of step, and the transmission kicks down instantly when called upon.

Absolute top speed is of little importance in a car of this type, but at Yatabe the best figure on the 1km straight was 150.6km/h, with an average of 149.9km/h on the 5.5km circular course. Given the manufacturer’s catalog figure of 155km/h, these results can be regarded as perfectly respectable.

The Crown’s engine, too, revs very smoothly right up to the start of the red zone at 6000rpm, and is in no way inferior to the Cedric’s in that respect. However, underhood noise–coming primarily from the cooling fan (despite the use of a fluid coupling)–begins to make itself heard from around 2500rpm.

The first impression one gets once underway is that the throttle is unreasonably heavy and acceleration feels painfully sluggish. Even when the throttle is pressed quite deeply–down to about one-third of its travel–automatic upshifts occur at very low speeds: The 1-2 shift comes at around 10km/h (about 1600 rpm), and the 2-3 at roughly 22km/h (around 1800rpm). From that speed, with the car in top gear below 2000rpm, acceleration is, unsurprisingly, extremely lethargic. The feeling is rather like trying to coax progress from a car with a slipping clutch: the tachometer remains glued to around 2000rpm, while the speedometer creeps slowly upward. For brisk acceleration, kickdown will not engage unless the driver stomps the throttle hard enough to feel as though their foot might go through the floor.

However, according to the standing-start acceleration figures, the unexpected result is that the Crown is slightly quicker than the Cedric. For example, the Crown’s 0–400m time is 20.4 seconds, some 0.7 seconds faster than the Cedric, and it also reaches 0–100km/h about 0.3 seconds sooner. By contrast, overtaking acceleration, measured as the time required to accelerate from a steady cruising speed to a specified higher speed using kickdown, is consistently slower than the Cedric’s.

This seemingly contradictory behavior can be explained as follows. The generally dull “feel” of the Crown’s acceleration is largely an illusion, created mainly by the unnecessarily heavy throttle (a trait common to Toyota twin-carburetor engines). The fact that the Crown’s standing-start acceleration–particularly up to the mid-speed range of around 80km/h–is faster than expected, and faster than the Cedric’s, is likely due to differences in torque-converter multiplication and planetary gear ratios. Specifically, the stall torque ratio of the converter is 1.9 for the Cedric versus 2.2 for the Crown, while the first- and second-gear ratios are 4.67-2.45 and 2.77-1.46 for the Cedric, compared with 5.28-2.40 and 3.25-1.48 for the Crown, giving the latter the numerical advantage. The final drive ratio, in fact, is the reverse, with the Crown’s 4.11 being smaller than the Cedric’s 4.38. But in terms of the overall gear reduction in first and second, the Crown still has the larger ratios.

Considering this, the reason the Crown is slower in overtaking acceleration can only be attributed to the time lag between pressing the throttle and the actual engagement of kickdown. In any case, the Crown Hardtop’s throttle itself is unreasonably heavy, even when one allows for the additional work of actuating the hydraulic control system of the torque converter. Simply lightening the effort would greatly improve the subjective “feel” of acceleration.

Using kickdown, the Crown’s maximum speeds in first and second gears are 52km/h and 88km/h respectively, corresponding to 5000rpm in each case. We also tried manually selecting the L and 2 positions and pulling the engine right up to the start of the red zone at 6000rpm, but even then we were unable to record decisively better times than with fully automatic operation in the D range.

Top speed was slightly lower than the Cedric’s, with a best of 147.1km/h on the 1km straight and an average of 143.9km/h on the 5.5km circuit. Given the Crown’s slightly inferior power-to-weight ratio, this result is to be expected. Strong winds were blowing throughout the test day, but under ideal conditions the manufacturer’s catalog figure of 150km/h does not seem unrealistic. Engine speed at that time was approximately 5600rpm.

Crosswinds affected the Crown far less than the Cedric, and directional stability above 100km/h was excellent. However, when running close to top speed, encountering a direct gust produced a strong sensation of aerodynamic force pressing the nose downward. Incidentally, the speedometer was unusually pessimistic for a domestic car, indicating 140km/h at a true speed of 145km/h.

Comparing the two cars in terms of power performance, both deliver extremely quiet and refined driving manners, but as the figures clearly show, even a generous description must rate their absolute performance as disappointing. For example, the 0–400m times of 21.1 seconds for the Cedric and 20.4 seconds for the Crown are decisively slower than the 19.7 seconds recorded in C/G’s test of the Corona 1600 EAT automatic. Of course, buyers who choose an automatic transmission are primarily seeking ease of driving in urban conditions, and in that sense the additional 75,000 yen (for both Cedric and Crown) over a manual gearbox is well justified. Nevertheless, the overall loss in performance is undeniably large. The Crown SL (125ps/5800rpm) can be equipped with the electronically controlled EAT automatic transmission for an additional 30,000 yen, but this option is not available in the better-appointed Hardtop Super Saloon. Even if EAT were fitted, however, the fact that manually selecting gears and revving to 6000rpm produces no improvement in acceleration times suggests that absolute performance would remain unchanged.

In conclusion, what the Cedric and the Crown lack most decisively is power. An engine of at least three liters would seem more appropriate for cars of this type. By way of comparison, the Mercedes-Benz 250 (2496cc, 130ps/5300rpm, vehicle weight 1390kg) with automatic transmission achieves a top speed of 174km/h and a 0–400m time of 19.0 seconds. The Mercedes does not use a torque converter, but instead uses a highly sophisticated automatic transmission that combines a fluid coupling with a 4-speed planetary gearbox, successfully blending the advantages of both manual and automatic gearboxes. While one may not be able to expect such an elaborate and costly transmission in a domestic car, an additional 1000cc and roughly 50ps of output would very much be welcome. (In anticipation of a rumored increase in the displacement limits for small passenger cars, it is said that both Nissan and Toyota are preparing engines of around 2.8 liters.)

Fuel Economy

The conventional wisdom that automatic transmissions are thirsty was borne out once again by this test. Steady-speed fuel consumption was measured on the 1km straight with the transmission in top gear in the D range. At all speeds from 40km/h to 120km/h, the Cedric returned figures that were 5-6% better than the Crown’s. With a compression ratio lower by 0.5 and a slightly inferior power-to-weight ratio, the Crown’s performance disadvantage appears to be reflected directly in its fuel economy. Over the total test distance of approximately 350km (of which about 150km consisted of testing at Yatabe), the Cedric averaged 5.6km/l, compared with 5.4km/l for the Crown, again giving the Nissan a small edge. In either case, fuel economy can hardly be described as good. Both cars require high-octane gasoline. Fuel tank capacity is generous, at 70 liters for the Crown and 65 liters for the Cedric. In both cars, a warning light illuminates on the dashboard when the remaining fuel drops to 10 liters.

Handling, Ride Comfort, and Braking

The Cedric GX and GL are fitted with power steering as standard equipment. In most cars, models equipped with power steering use a quicker steering ratio than their non-assisted counterparts, but in the Cedric this is not the case: its steering still requires no fewer than four turns lock-to-lock. Even turning a corner at an intersection requires nearly two full turns of the large-diameter steering wheel. Despite the test car being fitted with optional Dunlop SP68 175S-14 radial tires, steering response is extremely dull. With these large-contact-patch radials, the steering effort itself is about right, but on the standard cross-ply tires it would likely be too light to inspire confidence. Tire pressures were set at 2.1/2.1kg/cm², yet the sound of the tires picking up concrete pavement joints was conspicuously loud, especially because the overall noise level is otherwise very low. In fact, these radial tires seem to be a mismatch for the Cedric’s gentle, unhurried character, and are probably unnecessary.

The suspension is basically the same as that of previous Cedrics, but De Carbon gas-filled dampers have been adopted. Ride comfort is extremely soft, and small surface irregularities are absorbed exceptionally well. On the other hand, larger bumps elicit exaggerated motions, and on rough roads there is a constant chorus of noises from various parts of the body. Handling is not particularly distinguished, but is appropriate to the character of the car. In corners, the car initially responds with pronounced body roll and strong understeer, which it maintains up to fairly high speeds; ultimately, however, the tail breaks away first. Braking presents no particular problems. Pedal effort is light, and a deceleration of 0.75g was recorded with a pedal force of 20kg. The 0-100-0 fade test produced especially good results: the initial pedal effort of 16kg actually dropped to 13kg on the third through fifth stops (disc brakes tend to develop higher friction once warmed), and even by the tenth stop had only increased to 18kg. The final two runs were accompanied by billowing smoke, but the braking effect itself remained stable. A warning light on the dashboard illuminates when brake fluid falls below a prescribed level.

As for the Crown, despite being fitted with cross-ply tires, its steering response is superior to that of the Cedric, conveying road feel more clearly. The Crown’s power steering also requires roughly four turns lock-to-lock, but because its steering ratio varies between 20.5 and 23.6, response just off the straight-ahead position feels far more positive than in the Cedric. Steering effort is on the heavy side for a power-assisted system, certainly much heavier than the Cedric’s. Handling in corners is characterized by strong understeer throughout. There is insufficient power to overcome the large scrubbing resistance of the front tires, so speed is steadily scrubbed off in corners.

Ride comfort is significantly firmer than that of the Cedric, but both small irregularities and large bumps are absorbed extremely well by the suspension, and the body remains consistently flat. High-speed driving over rough roads revealed two notable qualities: exceptional body rigidity and very strong damping. The car remains stable and confidence-inspiring even when driven hard. As a result, pressing on in the Crown along a gravel mountain road leaves the Cedric struggling to keep up.

The previous Crown’s brakes used a 6-inch diameter split servo, necessitating relatively high pedal effort. In the new model this has been replaced by a 10-inch unit acting directly on the master cylinder, and the rear drums have been enlarged to 10-inch duo-servo types. Pedal effort with the new brakes is extremely light, and because pedal travel is short, they feel overly sensitive until one is used to them. The pedal itself is positioned high off the toe board, requiring an awkward lift of the foot, particularly for drivers who prefer left-foot braking (as the author does; with automatic transmissions this technique allows quicker, smoother progress). Braking power is adequate, producing 0.8g with a pedal force of 20kg. However, under emergency braking, the rear wheels locked completely despite the presence of a pressure-relief valve, leaving tire marks nearly 10 meters long. The 0-100-0 fade test yielded even better results than the Cedric’s: pedal effort rose from 14kg to only 16.5kg by the tenth stop. The Crown SL can be equipped with an electronically controlled anti-skid device to prevent early rear-wheel lockup (a 70,000 yen option), but this system is not available on the Super Saloon.

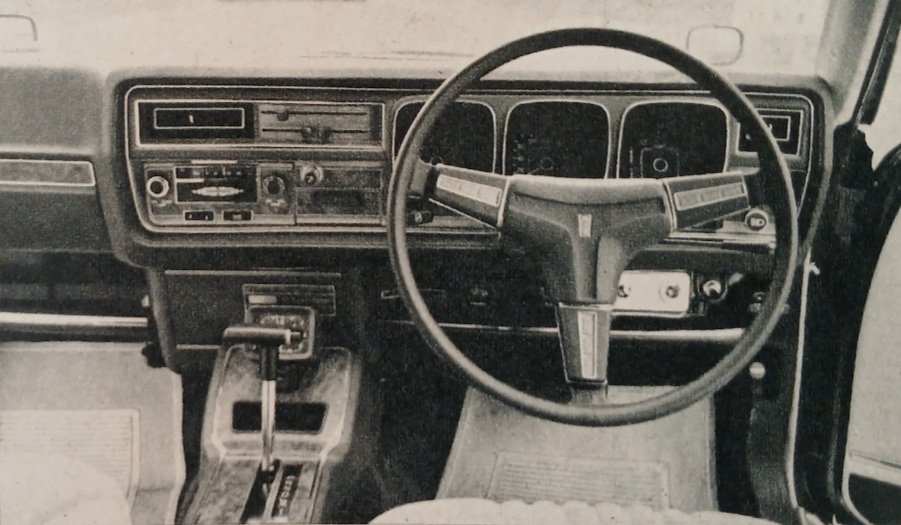

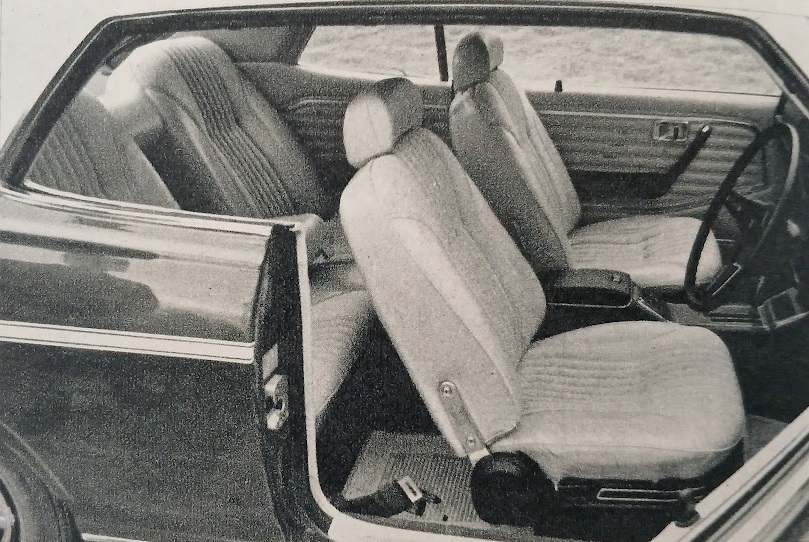

Interior and Equipment

The interior layouts of the two cars are so similar that switching from one to the other produces virtually no sense of unfamiliarity. In both, the front seats are generously sized individual buckets, with the shift lever located on the center console. In both, the rear seat is a near-sedan-sized bench that is comfortable for three adults. In terms of overall accommodation it is difficult to rank one above the other, but in the finish of individual details the Crown has a slight advantage.

As for interior equipment, one could hardly ask for more. Both cars come standard with power windows, heated rear windows (the Cedric’s includes a ten-minute timer), a dash-mounted AM/FM auto-tuning stereo radio, and radio controls for the rear-seat passengers. Air conditioning is, of course, available as an option. In addition, both are equipped with standard automatic door locks (electromagnetic solenoids on the Cedric; vacuum-operated on the Crown, which lock automatically at 20 km/h) and a remote trunk-lid release.

On the Cedric, the trunk is opened by pulling a lever beneath the dashboard, whereas on the Crown it opens by turning the ignition key one notch further in the “off” direction. As a result, when turning the engine off it was all too easy to move the key a fraction too far and inadvertently pop the trunk lid open, often at an inopportune time. One particularly convenient feature on the Cedric is the remote control for the fender-mounted mirrors, which eliminates the need to go back and forth from the driver’s seat to adjust them by hand. Another is the three-speed wiper system linked to the washer, with the first and second speeds operating intermittently.

The Crown, on the other hand, is fitted with a device familiar from American cars: if the driver’s door is opened with the key still in the ignition, a loud buzzer sounds continuously. Opinion within the test group was that this feature was more nuisance than convenience.

Although the interior equipment of both cars is, by any standard, almost excessively lavish, there is one area in which they both receive a failing grade: the heater. For reasons that are hard to fathom, neither car allows a moderate flow of warm air to be drawn in by ram effect alone, without engaging the blower. The heater simply does not function unless the blower is switched on, yet in both cars–even at the lowest blower setting–the airflow is ridiculously strong and excessively noisy. As a result, maintaining a comfortable cabin temperature requires constantly switching it on and off. This can only be described as an elementary design error.

In conclusion, speaking frankly, it is difficult to draw a decisive line between the Cedric and the Crown hardtops, whether in terms of performance or the richness of their equipment. If one were forced to choose, however, the Cedric emerges as the more softly tuned, comfort-oriented car, while the Crown, with its tougher suspension better suited to poor road surfaces, reveals a more overtly sporting character. If buying a Crown, it would make more sense to choose the SL, which is 10ps more powerful and 90,000 yen cheaper than the Super Saloon, and to specify the EAT automatic transmission for an additional 30,000 yen, which promises a modest improvement in performance. Alternatively, for those determined to have a Nissan automatic, the Skyline 2000GT Hardtop Automatic (950,000 yen) is far cheaper than the Cedric and offers little disadvantage in terms of accommodation. What one would lose in the trade are merely superfluous accessories. For those who find precisely such excess appealing, however, the Cedric Hardtop GX may well be the ideal car.

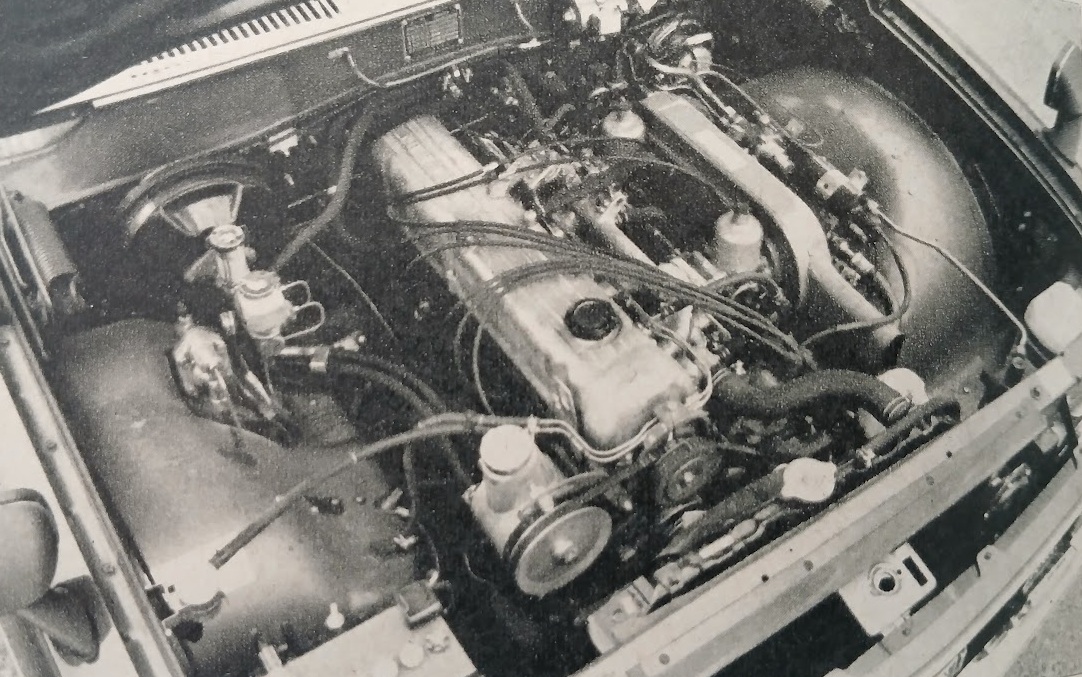

Postscript: Story Photos