Nissan Bluebird 1600 Coupe and SSS Coupe (1969)

Publication: Motor Fan

Format: Touring Report

Date: February 1969

Author: Atsuro Sasaki, Jun Todoroki, Motor Fan Editorial Staff (uncredited)

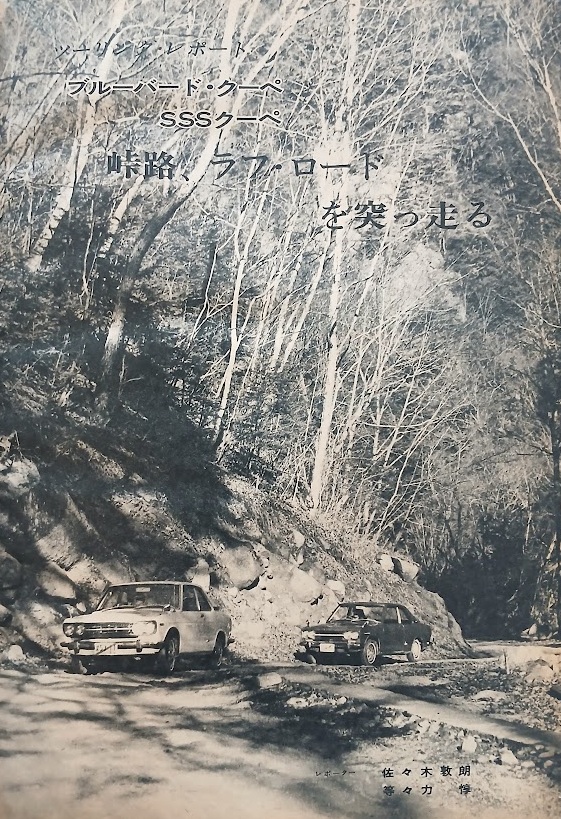

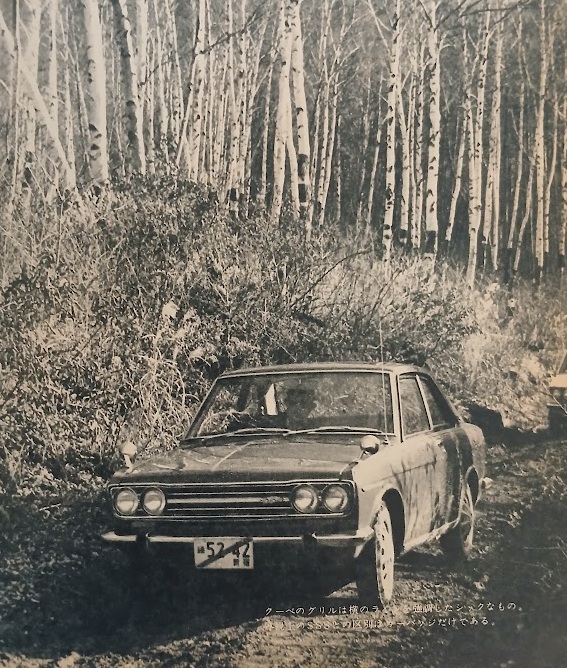

Bluebird Coupe and SSS Coupe: Charging Through Mountain Passes and “Love Roads”

Long rumored but slow to emerge, the Bluebird Coupe had seemed almost stubborn in its refusal to appear on the market. At last, in November 1968, it was released for sale. Motor Fan immediately set out to test its true worth over 600km of touring, running both the 1600 Coupe and the 1600 SSS Coupe side by side. Naturally, we planned a route that included as many driving conditions as possible, covering ordinary roads, expressways, and rough mountain passes.

Masculine Character Beneath an Unassuming Appearance (Atsuro Sasaki)

“A car for the man in search of romance,” reads the advertisement. Plus lines like, “It will make the driver feel young at heart.” Japanese advertising copywriters do have a habit of tossing out words carelessly. Still, that’s beside the point. At this stage in life I’m hardly dressed–or inclined–for chasing romance, so being asked to do a touring report on the Bluebird Coupe can only be explained by the fact that I’ve been writing nothing but practical articles lately. Besides, I’ve been familiar with the Bluebird ever since the 1200 days. The so-called “Dynamic” 1600–another thoroughly overused word–was something I wanted to try for myself.

I may not be chasing romance, but I did decide to conduct a truly hard touring test, covering five to six hundred kilometers and deliberately including some rough roads. That would allow me to put both the 1600cc power and the “coupe feeling” to the test. The route we chose ran from Tokyo to Atsugi to Odawara; then through Hakone, Otome Pass, and Gotemba; on to Lake Kawaguchi, Misaka Pass, Isawa, Kofu, Nirasaki, Masutomi Hot Springs, Shinshu Pass, Kawakami, Saku, Komoro, Takasaki, Kumagaya, and back to Tokyo. Five well-known mountain passes in all, including stretches of the old Saku-Koshu highway that are still unpaved, and even the mountain roads deep in Okuchichibu.

“Well, this is looking good,” I thought to myself with a grin. Romance had nothing to do with it.

The SSS’s Dash is Impressive

The day we set out from Tokyo, the rain that had begun the night before was still falling hard. The Saku region is deep in the mountains, and the route through Hakone and Misaka along the way can be troublesome if the weather turns to snow. The one saving grace was the unseasonable warmth. It hardly felt like winter at all. And if things did come to that, I’m at an age where turning tail and heading back can be done without much hesitation.

Casting caution aside, we tore away, the 1600cc powertrains yanking the tires off the road as we went. Strong stuff, indeed.

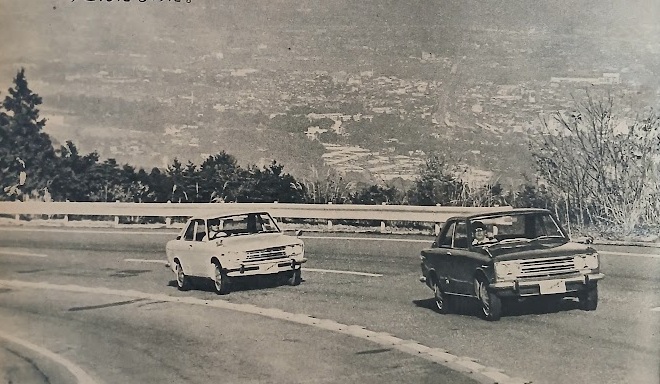

From Seta in Setagaya Ward we took Route 246 and joined the Tomei Expressway. In no time at all, the 1600 SSS pulled decisively away from the 1600 Coupe. Before I knew it, I was left behind. Still, although it fell back at first, the Coupe quickly caught up and matched the SSS’s pace.

For someone accustomed to driving a Bluebird 1300 sedan, the difference in power was simply night and day. It’s a matter of feel. I realized this all too clearly later when I switched over to the SSS and again became painfully aware of its greater output.

Fundamentally, strength is a good thing. That applies regardless of whether the driver is a man or a woman. The outcome, however, depends on how skillfully it’s handled: either you’re dragged around by the power, or you manage to make full and proper use of it.

At a steady 100km/h on the expressway, we spent the first five minutes testing acceleration. It was remarkably effortless and light on the nerves. The long pedal travel makes it easy to feel how much power is in reserve for a sudden burst. For someone like me who often drives on the Chuo Expressway and the Tomei, that’s very reassuring.

Criticism of the Bluebird Coupe’s styling and its mechanical details is covered elsewhere, so I’ll avoid it here.

Since the introduction of the 1600 series last autumn, several minor running changes have been made. One of these, oddly, is that the seat backrests seem to have been shortened. Being the timid sort who is constantly conscious of rear-end collisions, I felt a faint chill run up my spine when I noticed this. With this low backrest, even if one specifies the optional headrest, it doesn’t seem likely to offer much real neck protection unless it protrudes quite far forward.

Viewed from the rear, the coupe’s rear window has grown larger. A tall backrest could stand out awkwardly from this angle, looking rather ungainly. Perhaps it was lowered to restore the visual balance.

The steep rear window is aerodynamically raked–it is a coupe, after all. The large glass area is welcome, and over these two winter days it provided a much appreciated expanse of sunlight.

That said, anyone who takes pride in keeping their windows spotless will have a hard time when it comes to wiping the glass from the inside. I tried to do so by leaning back while seated in the rear seat, and it was quite an ordeal. When I resorted to a spray cleaner to get the glass truly clear, I nearly wrenched my neck in the process. It becomes a full-body exercise. Perhaps this really is a car meant for young, flexible people.

The Tail Lights Really Stand Out

As far as the instrument panel goes, there is no difference between the 1600 Coupe and SSS Coupe compared with their sedan counterparts. In both coupe and sedan, however, the speedometer face has been changed to polished aluminum since the 1968 model year, making it much clearer. The green nighttime illumination is especially bright and easy to read. The high-beam pilot lamp is now a strong red. On the 1968 models it was dull and hard to see when oncoming headlights were bright, but is now much improved.

Most impressive of all, however, are the tail lights. Like those of the Laurel, they are long and horizontal, with the turn indicators flashing along the entire width of each side.

In the rain on the Tomei Expressway–whether changing lanes or pulling into a service area–you can spot these lights immediately from behind. This is something you could fairly call a Nissan hallmark, born from constant awareness of high-speed driving. It’s a pity they didn’t feel inclined to equip the sedan with them as well.

In fact, these lights’ brightness is strong enough in close-following urban traffic to be a bit hard on the eyes for the car behind. Still, having the light spread straight across in a single horizontal band is surely safer than the small, low-mounted lamps used elsewhere. There is also an option in which the tail lights flow pop-pop-pop sequentially to indicate the direction of a turn. “Dynamic elegance,” perhaps. For high-speed touring, though, it feels more decorative than necessary.

Night Driving on Forest Roads, with a Deep Drop Below

From the Atsugi interchange we headed toward Odawara. The rain had stopped, and the blue haze of the Tanzawa and Hakone mountains began to open up. Taking the Tokyu Turnpike, we crossed Hakone Pass and from Hakone Town turned up onto the Otome Pass.

On these corners, anyone already familiar with the Bluebird sedan or SSS will feel right at home in the coupes. In terms of feeling, there is virtually no difference. Rearward visibility, however, is in another league. Especially with the rear backrest folded down, the view is almost too wide open.

In the SSS, there is what only barely qualifies as a console box, essentially just a small tray ahead of the shift lever. On a tour like this, one imagines it might hold toll tickets, sunglasses, a camera, or binoculars, but in reality it’s good for little more than chewing gum and a few coins. A camera, for instance, is better kept away from a place where it would be blasted by hot air from the heater. Dust also blows in there. It seems convenient at first, but in the end I found myself using the rear seat for storage instead…

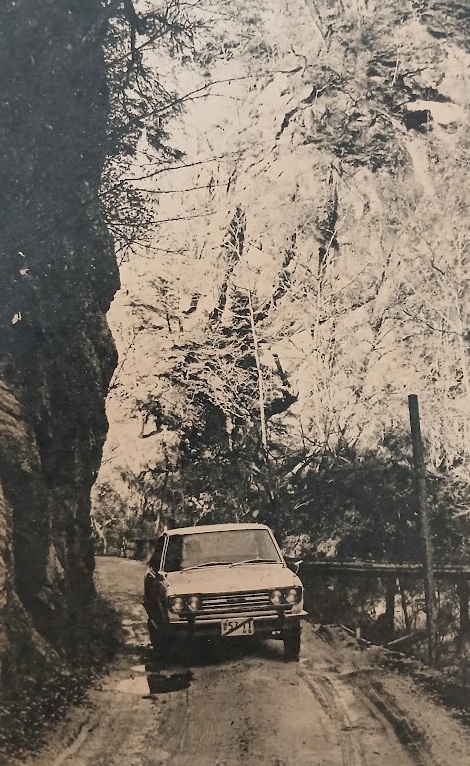

Leaving Kofu city, we continued from Nirasaki onto Route 141. From Sutama town we headed toward the Masutomi Radium Hot Springs. The road soon began a gentle climb–and then abruptly turned into rough terrain. It was still mostly mud, with a little gravel, and the bumps were severe.

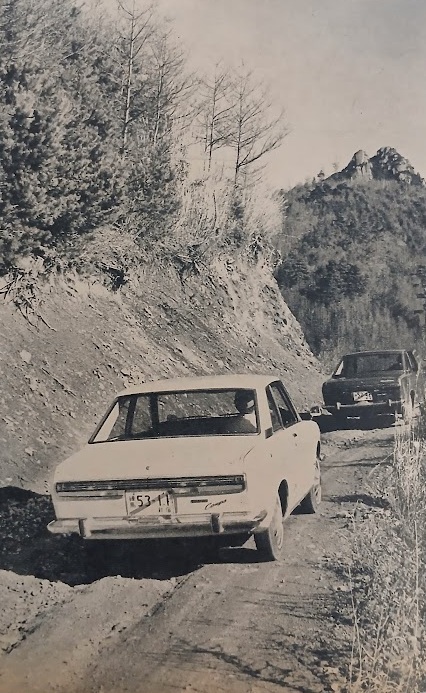

From the western edge of the Chichibu mountain range, the oddly shaped rock spires of Mount Mizugaki towered above us. Cold air flowing down the Shiokawa River blew into the cabin through the interior vents. The two coupes squeezed along the narrow one- to one-and-a-half–lane road, which was seemingly carved out of the riverside rock walls. It must have been quite a sight for anyone watching. For us, however, it was a desperate struggle.

Because we were following the Shiokawa River, I muttered–only half-jokingly–“Surely, there must be a village called Shiokawa somewhere,” as we passed the fork in the road. From there it was about 5.5km to Masutomi Hot Springs at Higashi-Obi. We stayed overnight.

Taking on a Real Rough Road

The next morning, we drove onto a stone road thickly glazed with frost. With a road clearance of 190mm, the Bluebird is probably among the most mountain-ready sporty cars. And with semi-trailing arms at the rear, it has full independent suspension. From my own experience of driving in the mountains, that matters a great deal.

But the road was harsh right from the start. When I pressed the accelerator to gain speed, my foot was shaken right off the pedal. “Tougher than the Norogawa forest road,” I thought. Then I glanced in the rearview mirror and saw a truck–which should have been slower than us–climbing up behind with an air of superiority. I pushed the Bluebird harder to gain some distance. Here, the power of the 1600cc was clearly evident. I remembered how I’d struggled in Norogawa and Sasago just a short while ago. In that sense, even the standard 1600–not just the SSS–seems capable of a new level of sporting enjoyment.

Along the way, we were diverted up into a ravine due to forest-road construction. The SSS managed to climb the slippery incline, but the coupe I was driving lost traction partway and became stuck. If I’d been alone, I probably would have given up there. But the construction workers and my traveling companions encouraged me, so I kept trying. I accomplished very little, and I couldn’t tell whether it was a lack of power or my own lack of skill. It reminded me of something a hardened touring driver once said:

“When you realize mountain driving is impossible, it’s best to give up cleanly and escape. Unless you’re someone who can put your full effort into getting out, you shouldn’t even try.”

Once the possibility of giving up enters your mind, your mindset itself becomes a negative factor, and can actually reduce your capability. Isn’t that a frightening thought? In the end, the coupe was hauled up with the help of a construction truck and the workers (including a large number of local women), but for a moment, any confidence I had gained over the past 200km was shaken. And to make matters worse, we missed the turnoff for the Shinshu Pass and ended up back at Shiokawa, the same place we’d passed the night before. In other words, we looped from Shiokawa to Masutomi, Kanayama, Kuromori, and Wada.

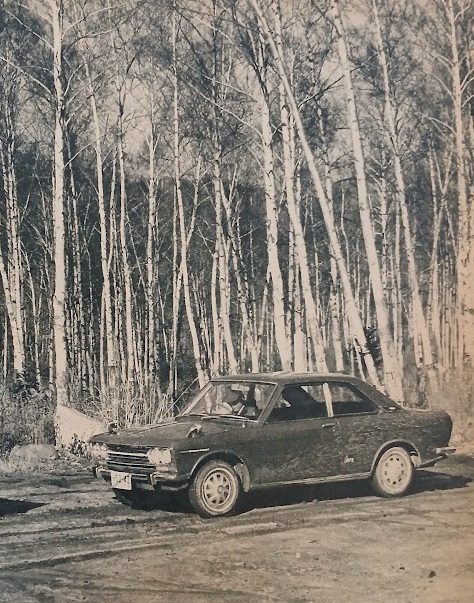

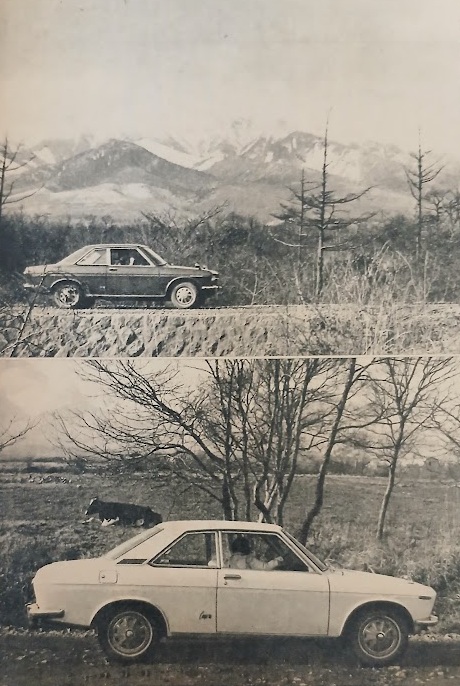

There was no choice but to return to the Saku Highway and blast across the Yatsugatake Highlands. Almost the entire route was rough road. Leaving behind the vast foothills of Umanohara and Nobeyahara, we charged ahead with the main peaks of Gongen, Amimanjo, Kokenda, Akadake, and Yokodake rising ahead. We were doing roughly 60-70km/h. The SSS drifted through the wide curves, while the coupe lagged slightly behind.

At the highlands, we took the opportunity to stop and check the course. We refueled, calculated fuel consumption, and also checked how much space could be created inside the cabin to rest and take mid-trip notes.

We folded down the rear seatbacks. Sliding the front seat all the way forward, we then folded the backrest down onto the seat cushion. The rear of the backrest is covered in the same padded vinyl leather as the front. Sure enough, the backrests line up completely flat. I lay down on my stomach and spread out the map. Even if I shuffled around, I didn’t bump into anything. There was room to use a calculator. Very nice.

I put a cigarette in my mouth. Then I realized there wasn’t an ashtray. I sat up, reached forward, and stretched for the one in front. And that’s when I thought: this car is really meant for solo travel or couples. If four people were aboard, you’d be kicked out of the car. So it really is a romantic car, after all.

Impressive Fuel Economy: 10.7km/l in the SSS

I’d like to share the fuel consumption data we calculated at that time. It was only partway through the route, but we planned to measure the two sections separately and connect them later.

Between Tokyo and Saku, the Bluebird 1600 Coupe had traveled a distance of 337.1km and used 34.0l of fuel, resulting in an average fuel consumption of 9.91km/l. The SSS Coupe had traveled 338.9km and consumed 34.7l, for an average of 9.77km/l.

This fuel economy is commendable given the speeds and the steep mountain grades–and these were new cars with only about 1,000km on the clock.

After this brief stop, we drove from Komoro to Karuizawa, then descended the Usui Pass on Route 18/17 to Takasaki and Kumagaya, then continued south down Route 16 from Higashimatsuyama, finally returning to Tokyo. On this section, the SSS Coupe achieved 10.7km/l. The 1600 Coupe, however, began to show abnormal carburetor behavior around Usui, so we stopped to have the throttle adjusted and lost a significant amount of time. As a result, its fuel-economy figures are not strictly accurate.

Between Saku and Tokyo, the Bluebird 1600 Coupe traveled 229.4km and used 22.0l, for an average of 10.77km/l. The SSS Coupe traveled 289.0km and used 27.0l, for an average of 10.7km/l. (Note that the extra distance traveled by the SSS was for contact with the service shop.)

With figures like these, even the budget-conscious “older gentleman” who worries about fuel bills might find this car surprisingly appealing.

So, the car has romance, and it is also strong on the highway. When the Tomei Expressway is fully open, it will show even greater value. It may sound like excessive praise, but this is a car with a masculine feel that belies its gentle appearance. It is by no means only for young people.

Hidden Potential is the Real Attraction (Jun Todoroki)

It is only natural to assume that the basic design of the Bluebird (510 series) was originally conceived with the 1600 engine in mind.

When the 1300 debuted as the New Bluebird in the summer of 1967, many people were surprised at just how oversquare its bore-stroke dimensions were (83mm × 59.9mm).

And because the 1600 SSS announced at the same time shared the same 83mm bore but used a 78.7mm stroke, it gave the impression that the SSS engine was in fact the base design, and that the 1300 was simply a downsized version of it.

As a result, the predictions that the Bluebird would eventually be upgraded to a 1600cc model were almost inevitable. It was the kind of thing one could sense was already in the works.

Similarly, in terms of body styles, the two-door SSS that existed in the old Bluebird (410 series) lineup disappeared when the 510 series arrived. So there was plenty of reason to expect that a coupe would soon appear as a rival to the Corona Hardtop.

So the introduction of the Bluebird Coupe was not a surprise either. Rather, it felt like a car that had been destined to arrive.

With that in mind, we set out to test the true potential of the long-awaited “Dynamic Series” engines, and we also drove the coupe–whose styling remains close to that of the sedan–in a fairly severe, aggressive manner to see if we could draw out a sportier feel.

Improved Wipers

After we took delivery of the cars, we headed straight onto the Tomei Expressway through the rain. The first thing we noticed was that the wipers had been changed from the former symmetrical type to a parallel-sweep design. On earlier 510-series cars, the parked position of the wipers interfered with the driver’s field of vision, and when operating, they left an annoying uncleared V-shaped area at the top of the windshield. These shortcomings have now been eliminated.

When driving at high speed in heavy rain, wiper lift is a frequent complaint. In the case of the Bluebird, the SSS has traditionally been fitted with finned wipers to prevent this. In the Coupe series as well, the SSS is so equipped, while the standard 1600 is not. In this particular test, no practical difference was felt between having the fins or not; however, since the performance gap between the two models has narrowed considerably, one wishes that such a worthwhile feature had also been adopted on the 1600.

As long as one remains on the highway, there is almost no difference in performance between the 1600 and the 1600 SSS. Both will accelerate easily to around 130km/h on half throttle. This is hardly surprising, since both share the same 4-speed gearbox ratios and the same final drive. (All Coupes use a 3.90 final drive, taller than the 4.11 used on the 1600 sedan.)

The real differences lie in the carburetion–twin SU carburetors with a 9.5 compression ratio for the SSS, versus a single two-barrel, two-stage carburetor with an 8.5 compression ratio for the 1600 Coupe–as well as in the brake systems (the SSS uses front disc brakes and rear leading-trailing drums with servo assistance, while the 1600 Coupe uses front twin-leading drums and rear leading-trailing drums), and the instrument panel. Considering the extent of the changes, the SSS’s price of 760,000 yen–some 65,000 yen more–begins to feel a little on the high side.

An “Easy-to-Handle Wolf”

On the Tokyu Turnpike, there was almost no traffic, allowing for a high-average-speed climb with plenty of momentum.

One thing that stood out in this section was the clutch feel. While the 1600 had no issues, the SSS’s clutch seemed somewhat heavily burdened. Given that the engine is more highly tuned, transmitting that stronger torque–13.5kgm at 4000rpm–may be asking a lot of it. When we stopped and I caught the faint smell of a heated clutch disc, I was reminded that I’d experienced the same thing before in the SSS sedan I drive regularly. Of course, it may have simply been because it was a brand-new car, with only about 1,500km on it, and the clutch hasn’t fully settled in yet…

From Hakone, we crossed over to Gotemba, then on to Fujiyoshida. After passing through the Misaka Tunnel and onto the Koshu Highway, we enjoyed a completely traffic-free run along a smooth, open drive. But on Route 20, traffic began to slow to a crawl.

Compared with the 1300, the 1600 Coupe’s increased power (from 72ps to 92ps), in combination with the 4-speed gearbox, allows both the driver and the engine to maintain slow, steady progress without stress. The synchronizers are of the Porsche-type servo design, with a shift feel often described as “stirring a spoon through honey,” and changing gears never becomes a chore. Once moving in second or third gear, you can even indulge in a lazy driving style, scarcely bothering to shift at all. The SSS Coupe is equally flexible.

On the first day, we branched off from Nirasaki onto the old Saku-Koshu route, then turned into the mountains from Sutama Town and headed for Masutomi Hot Springs, covering a total distance of 245km. Since more than three-quarters of that distance was on paved roads, we didn’t have much opportunity to fully exploit the virtues of the four-wheel independent suspension. As for the rear seat, a defining feature of the Coupe, we mostly used it as a luggage space, with the seatback folded flat. For long-distance travel this proved extremely convenient. For a two-person tour lasting a week or even ten days, the cargo area can be considered more than sufficient. Moreover, there are pockets on both sides large enough to hold four or five weekly magazines, making it easy to toss in maps, notebooks and such.

The 4-Wheel Independent Suspension Shines on Rough Roads

From Masutomi, we headed along the forest road toward Shinano-Kawakami, passing through the remote Kanayama Pass at the edge of the Chichibu Mountains. The previous day’s rain had turned the road into a muddy, slippery, steep, and relentlessly challenging route, made even worse by construction work. Still, the semi-trailing-arm rear axle proved its worth: it tracked the rough surface with precision—almost as if it was feeling its way over the bumps. Even with ordinary bias-ply tires, we enjoyed surprisingly strong grip. That said, these tires will not satisfy every owner.

Since the coupe is intended to be sportier and more upscale than a simple two-door sedan, it seems reasonable to ask whether radial tires should be standard equipment, at least on the SSS. After all, even some of the sportier domestic 1000cc models already come standard with radial tires.

The front suspension is a strut type, but the springs feel slightly too soft. The damping is effective, but on rough roads the initial compression is too deep, and there were several moments when the car nearly struck rocks with its underbody. Still, the front-to-rear balance is excellent with one or two occupants, and the car recovers quickly from disturbances. If the driver chooses the line carefully, spirited off-road driving is possible, and the Bluebird’s reputation for strength on rough roads is clearly felt in these coupes.

On the Difference in Brakes

On the return trip, we passed through Nobeyama and Saku, then headed east from Komoro on National Route 18. We descended Usui Pass to Matsuida in a brisk 21 minutes, threading through fairly heavy traffic. On a long downhill like this, the SSS’s servo-assisted disc brakes, with their precise, stable response, are a welcome asset.

There is none of the vague, unreliable feel often associated with disc brakes. Braking force builds in exact proportion to pedal effort, and at all times they give the feeling of simply scrubbing off speed, smoothly and naturally. Even with repeated use, there was virtually no sign of fade.

By contrast, the 1600 Coupe’s twin-leading/leading-trailing drums (without servo assistance) cannot be rated highly. Poor adjustment may have played a part, but even so, it was hard to escape the impression that the car is under-braked for this level of power. If this is where the price difference shows itself, it is regrettable–though at least the SSS-spec system is available as an option.

On flat national highways, there is little opportunity for spirited driving, so I turned my attention back to the interior. In the 1600 Coupe, the instrument panel is largely unchanged from that of the 1300 Deluxe. The main difference compared with last year’s 1300 Deluxe lies in improved secondary-impact safety: the knobs and switches are now larger and made of a softer material. Other changes are minor, such as the relocation of the interior light from the right-side center pillar to the middle of the headliner.

Access to the rear seat is aided by front seats with a “walk-in” sliding feature, and the wide door opening avoids unnecessary contortions. The rear seat offers perfectly adequate comfort for two occupants, and allows the car to fulfill the role of a two-door sedan.

The SSS shares the same seats and rear compartment, but its superb instrument panel is worthy of the more powerful engine, and can be called one of the finest among domestic cars. The basic design remains much the same, but the previously silver-rimmed round gauges are finished entirely in matte black, and the turn-signal indicator is enlarged for better visibility. The steering wheel is wood-rimmed, with a thick, solid grip that reaffirms the car’s high-performance character. The spokes, too, are finished in matte black, with nothing to distract or irritate the driver’s eye.

If there is a flaw, it is the glovebox latch, which is too loose and tends to pop open with even slight vibration. This occurred in both the 1600 Coupe and the SSS Coupe, and it is something the manufacturer would do well to address.

A Coupe with Strong Practicality

Although these cars are called coupes, their underlying concept places strong emphasis on practicality. In other words, the 1600 Coupe can be seen as something like a two-door Deluxe in 1600cc form, while the SSS is best understood as a genuinely all-around sporty car. In fact, it comes off as the true mainline expression of the SSS idea, to the point that the sedan almost feels secondary.

For that reason, neither car has a flashy presence. Instead, they are ideally suited to owners who take pride in “hidden potential beneath a calm exterior.” The powerful engine, combined with ample flexibility, seems even better matched to the coupe body than to the sedan.

Postscript: Story Photos