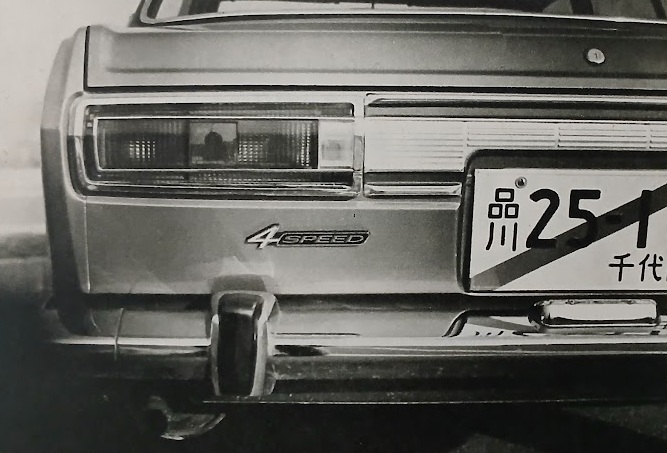

Nissan Bluebird 1600 Deluxe (1969)

Publication: Car Graphic

Format: Road Impression

Date: February 1969

Author: Kenji Kikuchi

Road testing the Nissan Bluebird 1600 Deluxe

The C/G test group has hoped to see a 1600cc single-carburetor model or a 4-speed floor-shift model added to the Bluebird series for some time. For an example of how successful such variations can be, one needs to look no further than Nissan’s own Sunny: when the so-called “Sports” model with a 4-speed floor shift was introduced, it was not only far more lively than the 3-speed column-shift version, but also made the car easier to drive. For those who felt that the 3-speed column-shifted Bluebird 1300 lacks spirit, but didn’t want to drive something as hot as the 1600 SSS, a middle-ground specification with a single carburetor and 4-speed floor shift promised to be ideal. Therefore, although the newly released 1600 series might seem to have arrived a little late, it can be said to be an eagerly-awaited arrival. Before we get into the driving impressions, let’s start by taking a look at the Bluebird “Dynamic Series” of 1600cc models overall.

The newly established Dynamic Series consists only of four-doors, including the existing 1600 SSS, Deluxe, Standard, and Wagon. For those who want a 1600cc two-door, the subsequently announced Coupe (also available in both SSS and single-carburetor versions) is intended to meet that demand. In outline, the 1600 uses a detuned version of the SSS engine, and it was introduced in a slightly refined version of the 1300 body, positioning it between the SSS and the 1300 models. In December, the 1300 models began using the same revised body as the 1600, and a 4-speed floor shift became available. This has given the current Bluebird series a wide range of variations, from the 1300 up through the SSS coupe.

As mentioned, the new 1600’s engine is a detuned, single-carburetor version of the L16 twin-SU-carburetor unit from the SSS. As such, it is a 1595cc inline-four SOHC with a bore and stroke of 83mm × 73.7mm, producing a maximum output of 92ps at 6000rpm (the SSS produces 100ps at 6000rpm) with an 8.5:1 compression ratio (9.5:1 in the SSS) and the aforementioned single two-barrel carb. Maximum torque is 13.2kgm at 3600 rpm (13.5kgm at 4000 rpm for the SSS). Compared with the 1300, which produces 72ps at 6000rpm from 1296cc, the engine displacement is 32% larger, and output is 28% higher. Aside from being detuned, it is basically the same engine as the twin-carburetor L16, but modified in several details.

For example, the intake and exhaust valves are shared with the L13 (1300cc) engine; the exhaust valve seat material has been changed; the valve oil seal material has been changed; the metal used for the crankshaft bearings is F500 instead of the SSS’s F770; the piston crown shape is revised; the air cleaner is different; and the intake and exhaust manifolds are reshaped. These changes were all necessary due to the change from a twin carburetor to a single unit, and are intended to improve practicality. Other changes include the camshaft, the carburetor itself, naturally, the addition of an automatic choke, and revisions to the blow-by gas reduction system. In short, the new 1600 engine occupies an intermediate position, combining the practicality of the 1300’s L13 with performance approaching that of the SSS’s L16. The clutch is the same diaphragm type used in the 1300 and SSS, but the diaphragm spring’s set load differs from the SSS specification, and the clutch pedal ratio is also different.

Three gearboxes are available: a 3-speed column shift, a 4-speed floor shift, and a Borg-Warner 3-speed automatic. The 3-speed column shift and automatic are carried over from the 1300, while the newly added 4-speed floor shift uses the same gear ratios as the SSS. The difference is that the SSS’s gearbox is a Porsche-synchro type, whereas the new 1600 uses a Borg-Warner synchromesh type shared with the Laurel and Skyline Sporty Deluxe. The final-drive ratio varies depending on the transmission. The 3-speed column shift and automatic use a 4.11 ratio (the 1300 uses 4.38), and the 4-speed floor shift uses the same 3.90 ratio as the SSS.

The four-wheel independent suspension, with double wishbones and coils at the front and semi-trailing arms with coils at the rear, is basically the same as in the 1300 and SSS. The only thing that has changed is the use of a dynamic damper for the mounting of the rear suspension member, similar to that used in the Laurel, to improve quietness at low speeds.

The braking system has also been greatly improved. First, the Deluxe, SSS, and Wagon now come standard with a tandem master cylinder. The SSS has servo-assisted front disc brakes as standard equipment, and these can be ordered as an option on the new 1600 4-speed floor-shift model. The steering uses the same recirculating-ball system and ratio, with the only change being that a collapsible steering column is now available as an option. The steering wheel now has a thicker padded horn bar, and the chrome trim has been removed to reduce glare.

Next, the exterior features a restyled front grille, tail lamps, and rear fascia, and shares several parts with the 1300 models. As mentioned above, the 1300 series recently underwent a minor change that adopted the same body as the 1600. Among these improvements, the foremost is the change from the widely criticized cross-type windshield wipers to a parallel type. Inside, padding has been added not only to the top of the instrument panel but also to the front and underside, to reduce the protrusion of the switch knobs, radio controls, and other parts. Other minor changes include a larger speedometer scale; dual headlight circuits and an improved fuse box, small marker lamps that illuminate along with the headlights; folding fender mirrors and breakaway-type interior mirrors (on the Deluxe series), less-intrusive interior door handles and window regulators, padded interior controls, and an improved glovebox with locking mechanism. All of these can be regarded as safety-related measures. Also, Nissan’s dual headlight circuit differs from Toyota’s in that, when one side’s fuse blows, that side’s light does not go out completely (as in Toyota’s system), but instead receives current from the side with the intact fuse and glows faintly, preserving the driver’s ability to judge the vehicle’s width. The seats are the same as those previously used in the 1300 series and SSS, aside from the addition of headrest mounting holes for both the front and rear seats.

Among the options available on the Deluxe, the main items are the collapsible steering column mentioned earlier, the brake servo, front disc brakes, an electric ventilation fan, a cold-climate heater, front and rear headrests, three-point front and two-point rear seatbelts, and an air conditioner.

This introduction has become quite lengthy, so let’s move on to the car provided for this test drive and its specifications. We tested a 1600 Deluxe 4-speed floor-shift model equipped with the optional servo-assisted disc brakes. The test car was essentially brand-new, with the total mileage having only just reached 1,000km.

On the road, what becomes immediately apparent is the car’s excellent power performance and general ease of driving. Compared with the 1300 model, the engine, with its 28% increase in output, delivers both strong acceleration at high speeds and, conversely, smooth and tenacious performance at low speeds, matching the 4-speed gearbox perfectly. For example, the increased low-rpm torque makes it entirely possible to start in second gear, and once in the flow of traffic, you can expect smooth acceleration even after shifting into top gear. Moreover, once in top gear, you can stay there, hardly ever needing to downshift even in city traffic. Furthermore, on highways such as the Tomei Expressway, acceleration from 80 to 100km/h in top gear has improved dramatically. As a result, when overtaking from around that speed, you can accelerate effectively without having to downshift to third, avoiding the accompanying increase in noise. Of course, throttle response is not as strong as in the twin-carburetor SSS, but for practical purposes it feels more than adequate.

The floor-mounted shift lever uses the same mechanism as that of the Laurel, so it feels the same in use. The lever stroke is just about right, not as long as that of the SSS with its Porsche-type synchromesh, and although there was still some new-car stiffness in the test car’s linkage, it slotted into each gear securely. The clutch pedal is much lighter than in the 1300, but as with the rest of the Bluebird series, the pedal stroke is long, requiring a large movement of the left foot. The accelerator pedal has become lighter as well, so that all of the controls, including the steering, are very light to operate, making the car feel immediately familiar and easy to drive.

Judging from the performance curves, the maximum speeds in each gear are roughly 45km/h in first, 76km/h in second, and 118km/h in third (all at 6000rpm). The car’s catalog top speed of 155km/h seems easily achievable given a 2km straight stretch without speed limits. At high speeds over 100km/h, engine and other mechanical noises are very low, and there is very little vibration. We took advantage of the opportunity to compare the 1600 directly against C/G’s own Bluebird 1300, and found the 1600’s noise level to be noticeably lower, likely helped by its taller gearing. In addition, when we accelerated away from a stop side-by-side with the 1300, the latter struggled to keep up with what felt like normal acceleration in the 1600, producing quite a racket in the process. We were unable to record data on acceleration times, but according to the manufacturer, the 1600’s 0–400m time is 18.3 seconds (17.7 seconds for the SSS). Compared with the 20.2 seconds recorded for the C/G Bluebird 1300, the 1600 is clearly much quicker.

Returning to the noise level at high speeds, one thing that did bother us was gearbox noise. Perhaps due to some play in the gears, the test car’s gearbox produced a light whine whenever strong engine load was applied, either during hard acceleration or under engine braking. In town, this was drowned out by surrounding noise and was not so noticeable, but it was hard to ignore when cruising gently on the highway, which somewhat spoiled the impression of low mechanical noise. Also, despite the Bluebird’s styling being referred to as the “Super Sonic Line,” wind noise is the most intrusive source of noise at speeds of around 120-130km/h. At such high speeds, one notices that the steering now feels firmer and more settled, and that straight-line stability has improved.

As mentioned, this engine has strong torque at low rpm. This is clearly demonstrated by the fact that it can move away from rest in second gear. The minimum speed in top gear is roughly 30km/h (about 1100rpm), and it is possible to accelerate from this speed, although it will be somewhat sluggish, and accompanied by some knocking.

Although the steering system itself is unchanged, more than a year has passed since the current Bluebird debuted, and incremental improvements made during that time have noticeably enhanced its handling. At the very least, the test car felt much better than the C/G 1300. Turn-in is lighter, and the car seems able to maintain a straight course more easily at high speeds. The body, too, has become sturdier than in the early models, and no matter how rough the road becomes, there is absolutely no sign of creaking or flexing in the body.

The brakes on the test car, equipped with the optional servo-assisted discs, are fully capable of coping with the improved performance. Switching from the C/G 1300 with its all-drum brakes, we immediately noticed that the 1600’s braking was much more stable and reassuring. Even from speeds above 100km/h, we were able to brake with confidence (which was not the case with the 1300), aided by the firm pedal feel and progressive braking force. The servo assistance feels natural and is not too strong, like the Laurel. In fact, if you were to drive the car without any prior knowledge, you might not even realize it was equipped with a servo. Another good point is the lack of squealing noise from the discs.

One thing that did bother us somewhat was the position of the brake pedal. Compared to the light, relatively long-stroke accelerator and clutch pedals, the brake pedal has a short stroke and is positioned higher than the clutch. This not only requires a large movement of the right foot from the accelerator to the brake, but in an emergency, the sole of the driver’s shoe could catch on the brake pedal. Hopefully, this was just an adjustment issue on the test car.

The handbrake lever emerges from under the dashboard, making it difficult to reach with the seatbelt fastened. This is unavoidable, since all Bluebird series cars, even the SSS, use a walking-stick type handbrake.

Finally, the front seats, which were known for the relatively high driving position they conferred, now seem to sit noticeably lower than before. Lower seats were recently adopted for the Laurel, so it is possible that the Bluebird’s have been lowered slightly as well.

Next, regarding minor improvements: the crossed-type wipers, which, as C/G tests pointed out repeatedly, left a large triangular gap in the center of the windshield, have now been replaced with parallel-type wipers. As a result, the wiped area now meets the required safety standards, and provides sufficient visibility in practical driving.

The padded, enlarged glovebox lid has a redesigned locking mechanism in which only the hook portion remains on the lid. On the test car, perhaps because the parts had not yet settled in, the lid popped open spontaneously on four occasions due to vibration while driving. As mentioned above, the window regulator handles and interior door handles have been redesigned for less intrusion, and are now covered with vinyl leather padding. While these are better from a safety standpoint, we found the window regulators to be extremely stiff, and the shape of the door handles made them awkward to use. We prefer the recessed door handles used in the Skyline and Cedric.

To close on some positive notes, the ventilation remains as strong as ever, and the ability to switch between headlight beams using the turn signal lever is very convenient in city driving. The speedometer’s revised scale, with coarser markings in the most frequently-used range between 40 and 100km/h, is also much easier to read than before.

Postscript: Story Photos