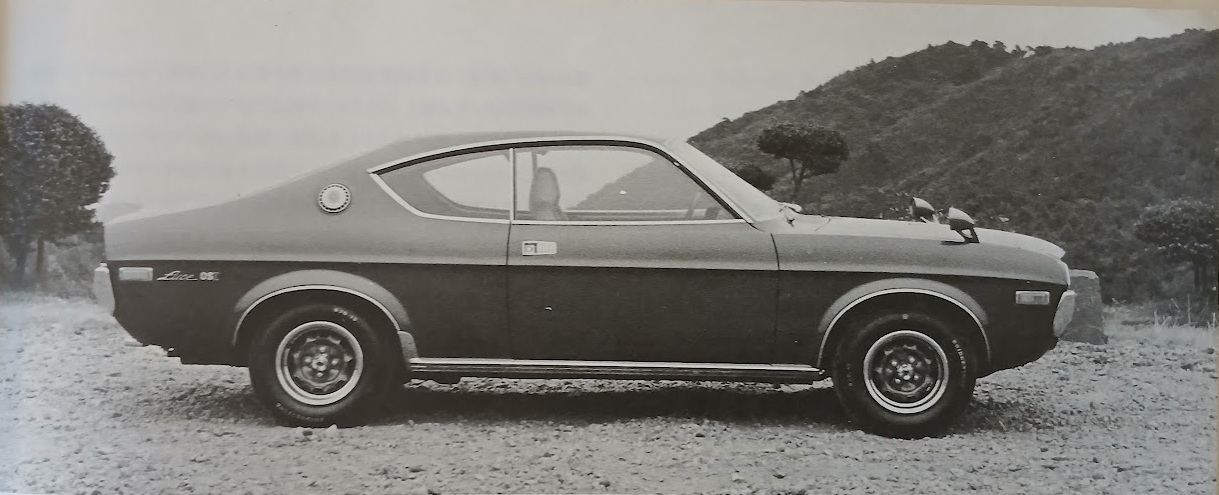

Mazda Luce Hardtop GS II (1973)

Publication: Car Graphic

Format: Road Impressions

Date: April 1973

Author: “C/G Test Group” (uncredited)

Summary: The highest-performance version of the new Luce, a smooth and quiet personal luxury car. Despite its attractive specs, maneuverability is only average among domestic cars, while ride comfort and livability are excellent. As with the AP model, fuel economy is poor.

Road testing the Luce Hardtop GS II

The new Mazda Luce series was just announced last October, and for this report, we tested the top-of-the-line, high-performance hardtop GS II over a distance of about 850km. We had already had the opportunity to test drive this model for a short time immediately after its announcement, and were particularly impressed by its handling, which was far superior to that of previous Mazda mass-market cars. In the road test in last month’s issue, we covered the sedan GR AP model, which is equipped with a thermal reactor for exhaust emission control, which is currently a hot topic. Contrary to what you might imagine from the “emissions-controlled” label, the engine in that car produces effective power, and the excellent automatic transmission is well matched to it. Another thing that made a strong impression was the well-balanced chassis, even when fitted with ordinary 6.45-13-4PR bias-ply tires on 5J x 13-inch wheels (which are still on the wide side for a Japanese passenger car).

Since even the mainstream sedan model rose above the usual standard of family cars, we were extremely interested in, and had high expectations for, the sporty version of the series, which has rims that are wider by another half inch, unusually fat B70-13-4PR tires (equivalent to 195/70-13 in radial terms) that were especially developed for the Luce, and two sturdy torque rods added to the rear suspension (which is a rigid axle with semi-elliptical leaf springs). The test car was the hottest model in the range, equipped with a 573cc x 2-rotor 130ps rotary engine without a thermal reactor and a manual 5-speed gearbox. It costs 1,040,000 yen with the optional power windows (30,000 yen). A Custom (a sporty version of the standard four-door sedan) and GR II, both with a reactor-equipped AP engine with 5 fewer horsepower, and a choice of automatic or manual transmission, are also available with this chassis.

Let us start with the results of the tests on maneuverability, which was our biggest area of interest. We were very disappointed in this regard. In short, the potential of the chassis is insufficient for driving this car actively, and it generally falls in the “dull” category, not going much beyond the level of existing domestic sporty cars (most of which have chassis that cannot keep up with their engines). If the swift horse that galloped through the mountain roads of Izu when it was first announced (see C/G, No. 139) was a Luce GS II, as it surely was on paper, then the GS II we drove for this test should be exactly the same. But when we actually drove it, its behavior made us think it was a different car altogether. The difference between the two cars goes far beyond the so-called degree of difference, such as differences caused by wear in components due to mileage, or the allowable production variation that occurs in mass-produced cars.

The first GS II we drove, which we praised highly, was without a doubt the best-handling Japanese car we have experienced. Despite its conventional chassis layout, its handling characteristics were virtually neutral, and even in high-speed cornering, the car cornered as if it was following rails, needing no corrections to the steering angle once applied, even under full power in third gear. The steering was quite heavy, but there was almost no free play near the straight-ahead, and while it was moderate in its responsiveness, its feel was at a level that could be called “textbook” for sports car steering, almost completely shutting out kickback from the road surface, despite the tires having high lateral rigidity. What made this maneuverability particularly outstanding was that it was combined with a very high level of ride comfort.

However, the GS II that is the subject of this second report, which included instrumented tests at Yatabe, had practically only one thing in common with the previous test vehicle: an excellent, solid-feeling ride regardless of the road surface. The biggest difference was that the steering was surprisingly imprecise, and not only was it not very sensitive overall, but there was also a lot of free play when pointed straight ahead (including pure mechanical play), with a “dead zone” of more than 10cm at the wheel rim. In fact, even if we turned the steering wheel vigorously left and right by about 45 degrees while driving straight at 100km/h, the car’s direction did not change much. What this means in practical terms is that, when driving on a highway with a strong crosswind, for example, you have to anticipate the dead zone each time you correct your course, which inevitably requires extra concentration until you get used to it.

In terms of cornering balance, the test car exhibited extremely strong understeer from start to finish. Even with the fat B70-13 bias-ply tires (Bridgestone Skyway Deluxe in this case), which are said to provide high cornering power comparable to that of 175SR-13 to 195SR-13 radials, it is difficult to stay on your intended line unless you keep increasing the steering angle, which is already exaggerated at turn-in by the free play, further and further toward the inside. In addition, the steering force is extremely heavy, and driving fast on a winding road will quickly tire your arms. The Mazda Capella does not show particularly satisfactory handling either, even the Coupe GS II, which has the highest-grade chassis tuning, and the Luce GS II is at about the same level. Considering the difference in tires (the Capella GS II’s are only 165S-13), the Luce could actually be said to be inferior. The strength of the understeer can be understood by saying that when you ease off the throttle when cornering, the nose tucks in, just like a powerful front-wheel-drive car. In addition, the roll angles are large, and in tight corners, the inside rear wheel tends to lift off the pavement, causing it to spin violently as the car loses speed.

We don’t know exactly what caused this dramatic difference in behavior, but the manufacturer’s official comment was that there should be no difference in specifications between the car we drove before and the one we drove this time. The best-case scenario would be if the standard Luce suspension had simply been installed by mistake. In our impression of our first drive in the early-production GS II, we wrote that we hoped the mass-produced model would be tuned with the same specifications, but unfortunately, it seems that those hopes have been dashed.

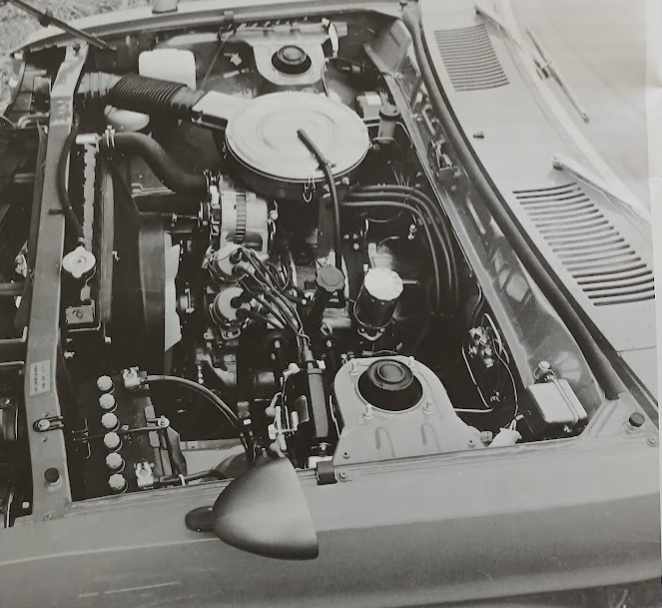

Of Toyo Kogyo’s 573cc x 2 12A-type family of engines, which is also common to the Capella, the GS II variant (called Type 3) without the thermal reactor produces a maximum output of 130ps/7000rpm, and a maximum torque of 16.5kgm/4000rpm, the highest power ratings of any commercially available Toyo Kogyo rotary engine to date. This output is sufficient for the GS II’s 1035kg weight, and it is not at all unpleasant in general driving, but since a special emissions controller is not installed, the carburetor is set as lean as possible to prevent CO2 emissions (by contrast, in the reactor-equipped engine, the mixture is made twice as rich as normal to promote the action of the reactor), and as a result, the engine overall lacks a strong punch, and is particularly slow to accelerate in the high-speed range above 5000rpm.

Unfortunately, on top of this, the engine in our test car was not in perfect condition, and the weakening of the high-speed range was particularly noticeable during the top speed test. Unusually for a Japanese car of this type, the Luce GS II’s top speed is not reached in overdrive fifth gear (0.862), but in the direct fourth gear. In the flying kilometer test, the car recorded a top speed of 177.4km/h (with 6900rpm on the rev counter, and 190km/h on the speedometer, the same as the catalog value), while in fifth gear, it was somewhat slower at 174.1km/h (at about 5600rpm, 181km/h on the speedometer). This is because the reduction ratio is smaller in fifth, reducing the driving force, which reduces the top speed. Moreover, when the car was left in fifth gear, driving into a headwind immediately dropped the needle on the rev counter to 5300rpm. However, if the engine had been in perfect condition, it would have certainly exceeded 180km/h, because the Capella GS II, which has almost the same gearing and 13-inch wheels, recorded 181.8km/h on the 1km straight section during the C/G test at Yatabe. The power-to-weight ratios are also very close, with the Luce at 7.96kg/ps and the Capella at 7.84kg/ps.

Standing-start acceleration and overtaking acceleration are also slightly slower than the first Capella GS that C/G ran at Yatabe. This may have been influenced by the engine’s maintenance condition at the time, but more likely it is due to Toyo Kogyo’s policy on rotary engine tuning. With each new model, the company’s rotary engines have become slightly smoother and more flexible. In fact, in the early Capellas, it was impossible to even measure overtaking data from 20-60km/h in fourth gear, as the engine suffered from knocking and could not accelerate. However, improvements have been made to make the rotary easier to handle by giving it more effective torque that allows it to run smoothly even at low speeds. And as a result, the top-end frenzy of the rotary engine has gradually faded away.

The 5-speed gearbox is the same as that installed in the Capella GS II and Savanna GT, with the fifth gear position at the upper right of the H-pattern. Therefore, we have the same complaints as we did in those cars about the shift feel, synchronizer capacity, and potential durability. Our test car, which had already been subjected to about 3,000km of rough treatment, always made a loud crunching gear noise when shifting quickly, such as in the acceleration tests. This tendency seems to be the rule rather than the exception, and even the 4-speed gearbox in the C/G Savanna, which is only used for normal everyday driving, is showing signs of weak synchronizers. It may be best to choose a model with the REMatic JATCO automatic transmission instead. It is 35,000 yen more expensive than the 5-speed model, but its effortlessness makes full use of the rotary’s smooth running characteristics. Moreover, it is fully suitable for sporty driving.

The front disc/rear drum servo-assisted brakes have sufficient stopping power for the car’s weight and power performance, except that the pedal feel is somewhat squishy and vague. In our fade test, we started from a standstill and accelerated until we reached a speed of 100km/h, then hit the brakes to decelerate at 0.5g until we came to a stop, then immediately accelerated again, and repeated this ten times. The pedal force of 16kg for the first stop only increased to 23kg on the last, so it can be said that the brakes’ fade resistance is extremely good.

As for fuel economy, the AP Luce we tested in last month’s issue was extremely thirsty, especially at low and medium speeds, due to the rich mixture used to promote the reaction of the thermal reactor, so we were hoping that the GS II, which does not have this feature, would improve upon it somewhat. However, after a test distance that included using all 7000rpm on the rev counter at Yatabe, Hakone, and Izu, the total fuel economy was just 5.35km/l. We think this is about the lowest figure this car can possibly achieve. As expected, the fuel economy at low and medium speeds was far better than that of the AP model, which gave us some peace of mind.

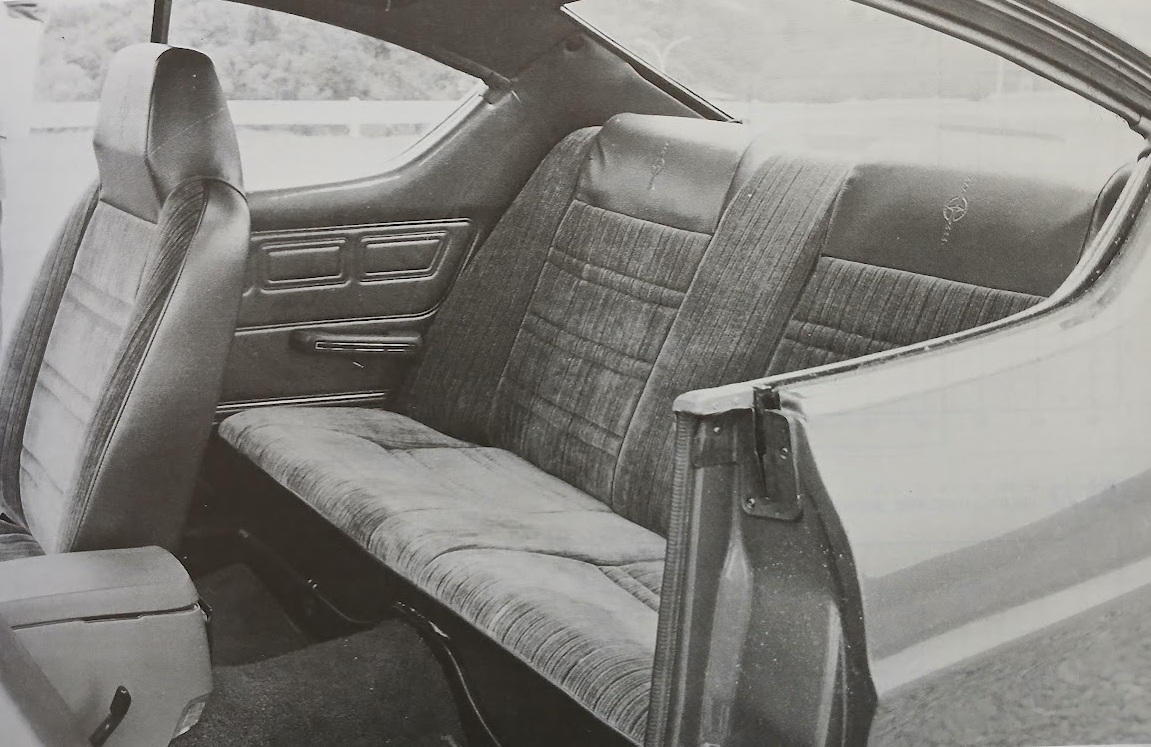

The so-called cockpit-type driver’s environment, with the entire instrument panel curved toward the driver, has good relative positioning of the steering wheel, pedals, shift lever, etc., allowing the driver to adopt a very natural driving posture. The driver’s seat itself is a little short in length, but its excellent shape supports the body well, and the thick, grippy corduroy upholstery is very practical. The rear seats are adequate in terms of size and legroom, but as is the fate of all fastback-styled cars, the rear window is quite steeply inclined, so if you lean back, the thick window frame will be right above your head. There are switches for the optional power windows at each seat position, and four are grouped together on the bottom right of the dashboard, but the latter are difficult to reach while driving (especially with the three-point seat belt fastened). The bi-level heater and ventilation are comfortable, and the outlets on both ends of the dash bring in a surprising amount of air. As for the minor details, the wipers are very effective (the GS II’s also have an intermittent setting) and clear the windscreen well.

After this second experience, and as far as we can judge, we can summarize the Luce Hardtop GS II as a Capella that has become slightly larger and more lavishly equipped. Its basic character as a long-distance high-speed cruiser remains unchanged. However, the attraction of this car compared to the Capella is that with only a few adjustments to the steering and suspension, it can become a truly sporty car that can fully utilize the power of the flexible rotary engine. The wide tread (1380mm)-to-height ratio of 1:1, of which the manufacturer is so proud, the 5.5J rims, and the extremely wide tires must have all been specified for that purpose. The Luce which is a true joy to drive has certainly existed; we have already driven it. What we hope is that the production Luce will be restored to the specifications of the “early production prototype,” or “press test car,” that we experienced on our first acquaintance in Izu.

Postscript: Story Photos