Isuzu Bellett 1600GTR (1971)

Publication: Car Graphic

Format: Road Test

Date: June 1971

Author: “C/G Test Group” (uncredited)

Summary: The ultimate Bellett GT. In exchange for a stiff ride at low speeds and excessive noise at high speeds, the performance and maneuverability are the best in the class, the steering is unmatched in its quickness, the power-off oversteer from the rear swing axle is moderately suppressed, it is extremely fast and exciting to drive on winding roads, and even with limited space in the back seat, which effectively makes it a 2+2, it is a very good car. The poor ventilation and heating system shows the age of the design.

Road testing the Isuzu Bellett 1600GTR

A full-scale test of the Bellett 1600GTR had been on the agenda for a long time. When it debuted in the fall of 1969, our road test editor had just broken his left leg, and was hesitant to use the GTR’s heavy clutch for extended periods while wearing a cast, so the editorial team published a simple road impression instead. Since then, there has been a steady stream of impassioned letters from enthusiastic Bellett fans calling for another test of the GTR. This reached a peak when, for various reasons, the Bellett 1600GTR was not included in the 1.6-liter sports coupe comparison test in the August 1970 issue of C/G, and letters of indignation piled up on the editorial desk. This clearly shows how the Bellett has captured the hearts of its enthusiastic fans, even though they are few in number, and how the GTR is their ideal model. We share the same enthusiasm for testing the GTR in earnest, so we decided to present it now, even though we know it is a little late.

After driving the Bellett GTR for the first time in a long time, we were reminded that this car, which is an old car in many ways, still has the best handling among domestically produced cars. First of all, the suspension of the GTR is much stiffer than that of the GT. The spring constant of the front coil springs is increased from 3.5kg/mm to 5.3kg/mm, and while the rear coil springs are the same, the number of transverse camber-compensator leaf springs is increased from one to three, and their spring constant is increased from 0.9kg/mm to 3.1kg/mm. The dampers are also much stronger, with 160kg rebound and 43kg compression (0.3m/sec) for both front and rear. The ride height is also 10mm lower. These specifications are almost the same as the Stage II suspension kit available for the Bellett GT. The tires are 165HR-13 radials on 4.5J rims as standard equipment.

The steering of the GTR is unrivalled in its quickness, not only among Japanese cars, where steering response is generally unreasonably sluggish, but also among European GTs and sports sedans. During this test, the car was driven alongside a 117 Coupe EC, and the contrast between the two cars is so striking that it is hard to believe they are made by the same manufacturer. The C/G testers who switched from the 117, which has extremely strong understeer, to the GTR found that the steering was so sharp and light that they turned the wheel too far and had to dial it back in the first two or three corners.

Even on normal roads, the GTR, with its stiff springs and sharp steering, makes quick cornering exceptionally fun, but really fast turns on a circuit require a bit of special technique and careful control. The 120ps is more than enough for a 970kg car, so as long as you are in the right gear, you can take corners quickly and tightly with delicate steering and throttle inputs. The reason why the GTR can do this is, of course, due to the characteristics of the rear swing axle, but it is also a basic weakness of this car. If you ease off the throttle while turning a corner near the limit, the nose suddenly tucks inward, just like a front-wheel-drive car (though for a completely different reason), which shows that there is moderate understeer with the power on. With the standard 165HR-13 radials (Yokohama GT Special XXs on the test car), if you stay on the throttle into a corner, the outside front wheel will eventually lose grip (sometimes quite suddenly). Therefore, to turn corners quickly with the standard tires, you instinctively take the following approach:

First, aim straight for the apex of the corner, brake just before the apex, and at the same time, turn the steering wheel slightly. Then, the rear wheels of the swing axle, which have become lighter due to the forward weight transfer, take a positive camber, and since their contact with the road is reduced, they slide easily, making the turn tighter than is aimed for with the angle of the steering. Once the direction has tucked inward, you immediately switch to full acceleration. In other words, instead of taking corners at the maximum radius of curvature as in normal situations, the car takes a line that connects two straight lines with a very small arc, taking advantage of the oversteer of the swing axle.

This method has two advantages. First, it is faster than a normal line with a large radius because it takes the shortest distance. Second, it goes straight until just before the corner, so the braking point can be delayed. This was a method favored by Stirling Moss in races, and he often used it to overtake faster cars in the braking area. Of course, you can’t and shouldn’t take corners like this on public roads, but it’s good to remember it as a special handling technique for the GTR. However, what you should be careful of is to never make sudden turns of the steering wheel. Sudden braking and steering is a no-no in any car, but in the GTR, even though the axle is low and stiff, it still has the weaknesses of a swing axle, so in the worst case scenario, it can easily lead to the car spinning out of control.

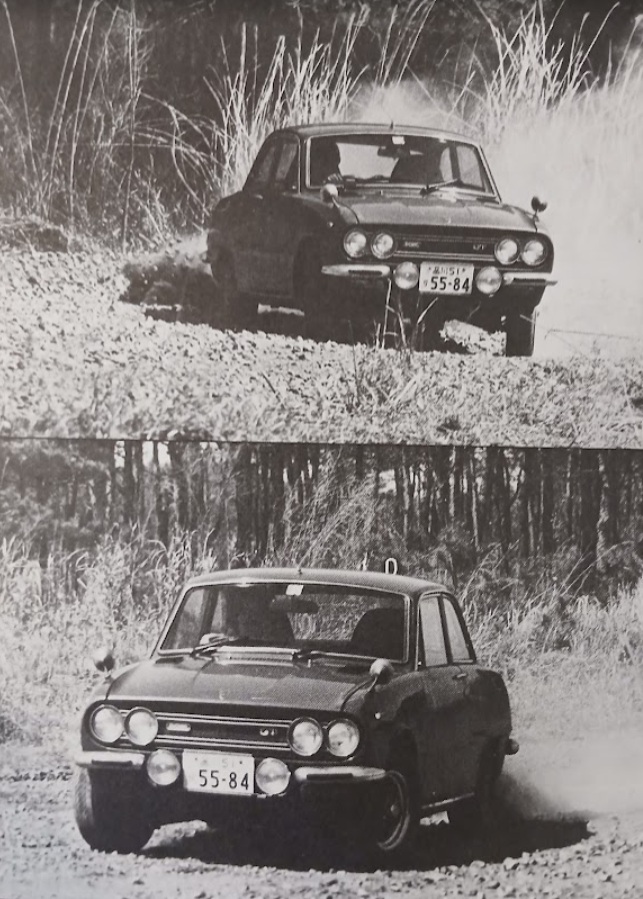

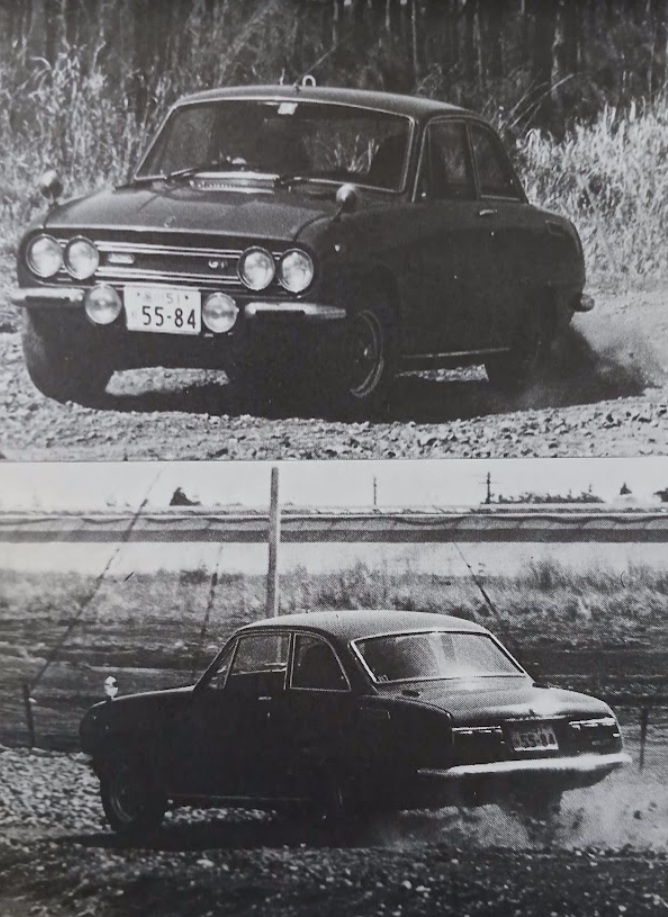

The GTR’s steering is moderately light except at very slow speeds. The price of this excellent maneuverability is the strong steering kickback, and concrete joints and cat’s eyes can not only be heard but also felt directly by the hands. At Yatabe, we tried driving on a gravel road similar to a rally course, and the effect of the all-wheel independent suspension and limited-slip differential was remarkable, and we confirmed that the straight-line stability on rough surfaces was particularly outstanding.

The brakes are a combination of discs and Alfin drums, and the pads are M33S type (M59 for the GT) which are highly fade-resistant. The increase in pedal force is compensated for by the installation of a small diameter Hydromaster servo. Also, the rear wheel brake circuit is fitted with a proportioning valve (PCV) to prevent early locking for complete security. The braking force is commensurate with the GTR’s dynamic performance. The pedal force is generally heavy by modern standards, even with a servo, and this feeling is particularly strong at low speeds in the city. However, the braking effect is linear and progressive according to pedal force, the front-to-rear balance is good, and they are generally the type of brakes that can be trusted in an emergency. In the 0-100-0 fade test, the pedal force only increased by about 20% on the tenth stop, and there is commendably little nose dive during sudden braking.

As expected, with the exception of top speed, the GTR’s power performance was confirmed to be at an extremely high level for a 1.6-liter class engine, even by global standards. It is slightly slower than the Galant GTO MR (125ps/6800rpm, 14.5kgm/5000rpm, power-to-weight 7.8kg/ps), and is on par with the Celica GT (115ps/6400rpm, 14.5kgm/5200rpm, power-to-weight 8.2kg/ps). Of course, both of those models have five-speed gearboxes, while the Bellett has only a four-speed.

The tire sizes of all three cars are 165-13, but the final gear ratios of the two cars with 5-speed overdrives are larger (GTO 4.22, Celica 4.11, Bellett 3.73), so the Bellett should be at a disadvantage in the 0-1000m acceleration test, where at least half the time is spent in top gear. However, in reality, the Bellett’s time (31.9 seconds) is almost the same as that of the Celica (32.0) and GTO (31.2), probably because the higher gear ratio (and therefore lower driving force) is offset by the smaller frontal area of the body.

However, we were very disappointed in terms of top speed. The day before we went to Yatabe, the engine seemed to be in good condition during high-speed driving on the Tomei Expressway, but when we actually conducted the top speed test at Yatabe, the engine simply would not rev in third or fourth gears. In the lower gears, it had no problem revving over 7000rpm, but in third gear it would not rev above 6000rpm, and in fourth gear it would not rev above 5100rpm. Therefore, the top speed was a dismal 147.5km/h on average over a 1km straight line. We suspected there was a problem with the ignition system, so we cleaned the spark plugs and tried various other measures, but to no avail. We had asked the manufacturer to perform thorough maintenance a month before the test, but it was clearly due to the engine being out of adjustment, and it is certain that the performance was far from the GTR’s true capabilities (quoted as 190km/h in the catalog, about 6700rpm in fourth gear). This was very disappointing for us, and we intend to retest the car as soon as possible.

Fuel economy, especially in a car of this nature, varies greatly depending on driving patterns. First, we measured constant-speed fuel economy as follows: 16.1km/l at 60km/h, 13.1km/l at 100km/h, and 7.6km/l at 140km/h. In terms of practical fuel economy, we saw a worst of 6.8km/l over a 227km stretch that included the testing at Yatabe, a best of 8.5km/l while driving at medium speed from Yatabe to Tokyo, and 7.5km/l while driving on the Tomei Expressway and in Hakone at high speed. The test car consumed a lot of oil, and it was necessary to top off one liter during the total test distance of 604km.

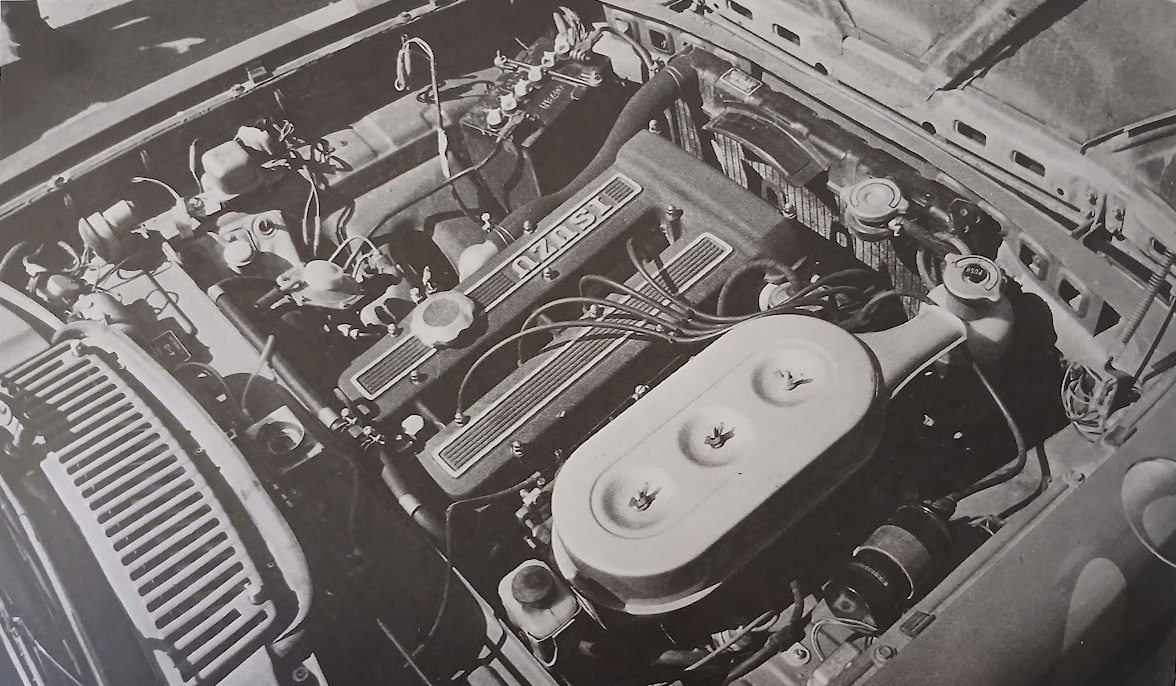

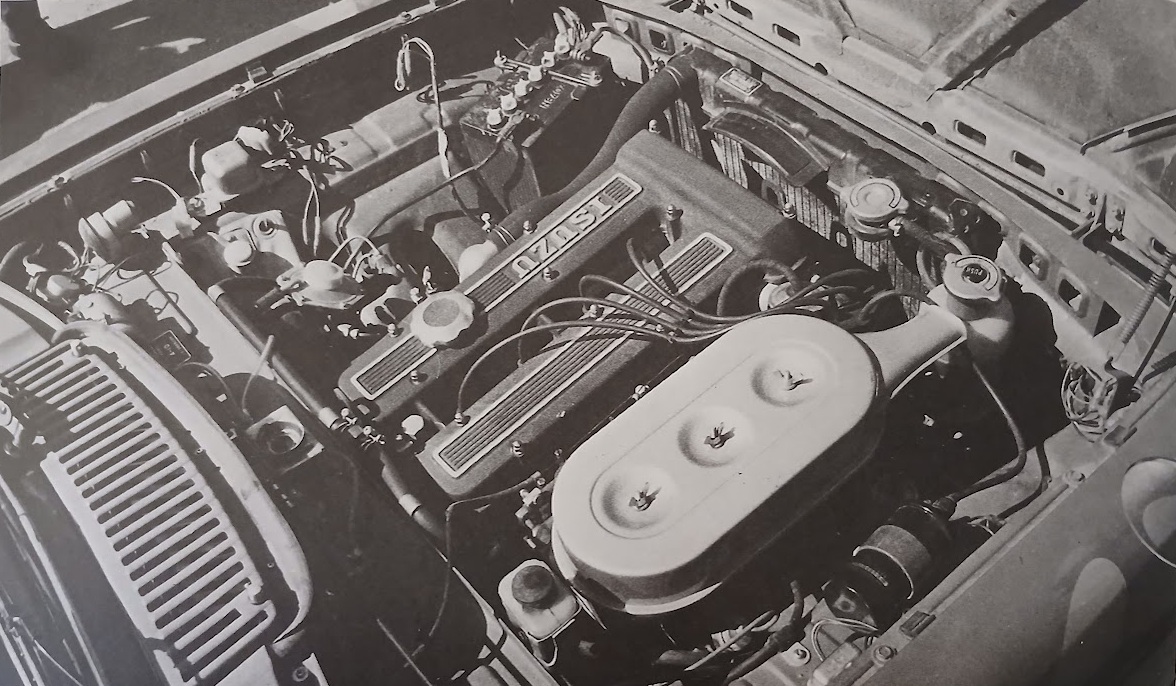

The four gear ratios are just right for the power and weight of the car. Revved up to 7000rpm, it can reach speeds of 58, 102, and 143km/h in first, second, and third gears. The engine itself is unusually flexible for a high-output unit, but because it is relatively high geared, 40km/h (about 1400rpm) is the minimum speed at which it can run smoothly at a constant speed in fourth. As mentioned above, the engine was not running well at the top end in third or fourth gear, but it was completely normal up to about 150km/h and maintained good performance throughout the four days of testing. During cold starts in the morning, we simply pumped the pedal a few times without using the choke, the twin Solex carburetors sucked in raw gas, and it immediately started up and smoothly idled at 900rpm. The compression ratio is high at 10.3, so if you suddenly press the pedal from below 2000rpm, it will detonate for an instant, but apart from that, the throttle response is sharp over a very wide range. The engine itself is extremely smooth at any speed from idle up to 7000rpm, but the engine mounts seem to be very rigid, so minute vibrations are constantly transmitted to the body. The drivetrain is also very rigid, and it responds immediately to the throttle, just like a rear-engine or front-wheel-drive car without a long propeller shaft.

The noise level is generally high by modern standards, but it is inevitable to some extent for an old design with a lengthy history. For hardcore GTR enthusiasts, the noise at high speeds is probably just a small price to pay for high performance. Our test took place in bad weather, with a momentary wind speed of about 15m/s, but the impact of crosswinds was not significant, and in fact, it turned out that the GTR far less affected than the 117 Coupe we drove the same day. Against a headwind, the 117 Coupe could barely maintain a speed of 140km/h, but the GTR was able to maintain a speed 10km/h faster than that with ease. Its straight-line stability in no-wind conditions was unparalleled, and it literally ran as straight as an arrow. Under ideal conditions, 160km/h (about 5600rpm) would be a perfectly reasonable cruising speed.

Since the small, lightweight GTR uses the same engine and gear ratios as the heavier 117 Coupe, the four-speed transmission is sufficient, and a five-speed gearbox is not needed. The thick, short gear lever is well-positioned, and shifts are quick and precise. The early Belletts had a lot of gear noise, but this has now been improved to the point where there is no complaint. Similarly, the clutch is heavy to operate, but the short stroke, for a Japanese car, is preferable. The limited-slip differential makes it difficult to induce wheelspin when accelerating off the line, so clutch slip must be used, but the clutch is well suited to this type of use. The pedals are well positioned, and heel-and-toeing comes very naturally.

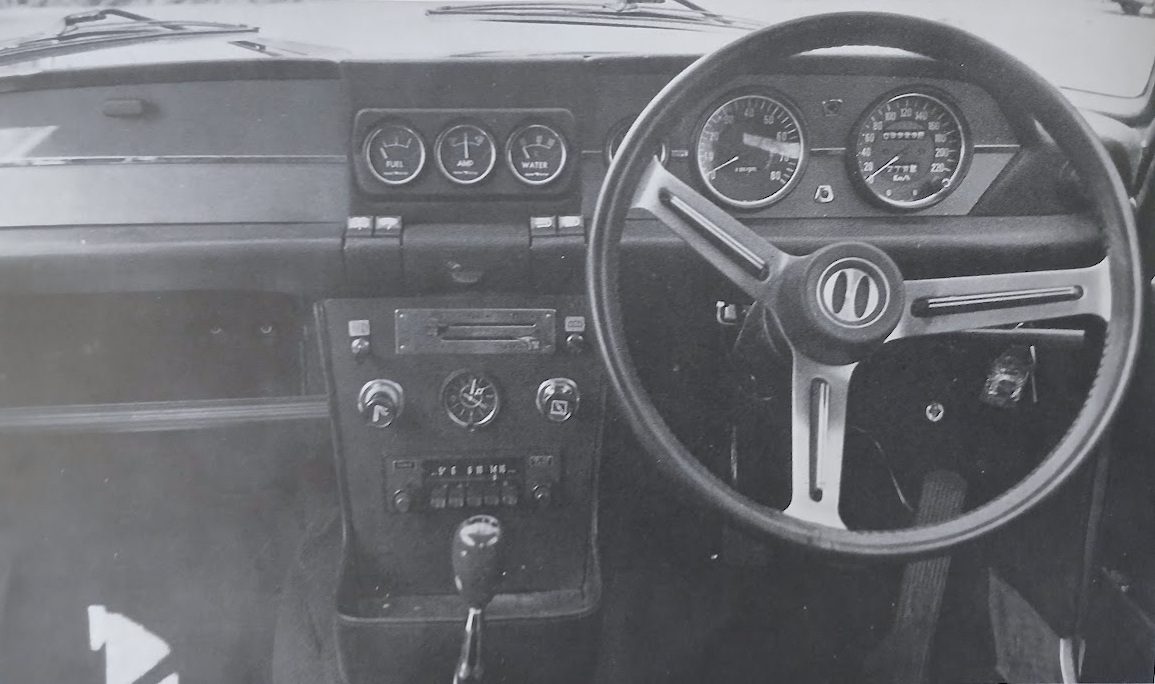

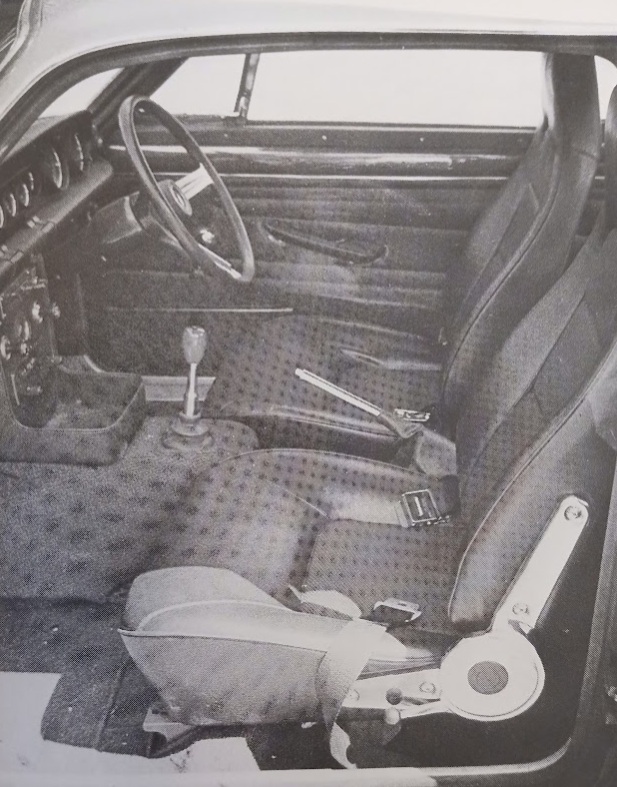

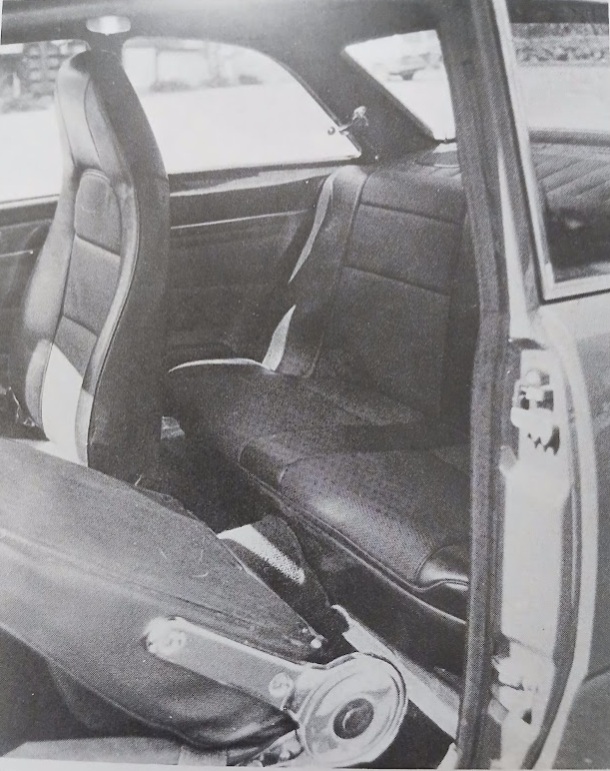

The GTR is effectively a two-seater, with the tight rear seat only usable as a spare seat to squeeze two people into in a pinch. If you look at it that way, it’s a very comfortable two-seater, and if you use both the back seat and the trunk, you can load up plenty of travel gear for long journeys. The driving position is excellent. Compared to more recent cars that make you feel like you’re in a glass box, where you can see out well but also feel exposed to the outside, the GTR, with its small glass area and low seats, gives you an indescribable feeling of security. The thick, leather-wrapped steering wheel is relatively high, and the scuttle is also high, putting the driver in the same posture as an Italian GT, like an Alfa, with its high-back seat that doubles as a headrest.

The seat is very comfortable, and the front cabin is sufficiently spacious, making it hard to understand why manufacturers unnecessarily widen their cars’ bodies every time they release a new model. However, the two-point seat belts are insufficient for the character of this car. The heater and ventilation also show the age of the design. The heater can only be controlled by the booster speed, and temperature control is not possible from inside the car, as it is controlled by a cock on the side of the engine. The nozzles on both sides of the dash only blow hot air in conjunction with the heater, and cool air at face level can only be obtained through the triangular vent windows. Since ventilation is insufficient, the windows tend to fog up in the rain, so the standard rear window defogger is appreciated.

Certainly, the Bellett GTR, whose basic design is nearly ten years old, is an old-fashioned car in many ways. On the other hand, it shows careful design and construction in many aspects, something that would never be allowed in a modern, thoroughly standardized product. The only real problems are the heater and ventilation, and if these small details can be improved, the Bellett GTR will have a long life ahead of it. However, the price of 1.1 million yen remains a big obstacle. Long live the Bellett!

Supplement: from July 1971 issue

As you all know, the 1600GTR we tested in last month’s issue had an engine that was not in perfect condition, resulting in a dismal top speed of 147.5km/h (the average measured over a 1km straight line). In first and second gears it could easily reach 7000rpm, but in third gear it could not rev over 6000rpm, and in fourth gear it hit a plateau at just 5100rpm. This was certainly far from the GTR’s true potential maximum (190km/h, according to the catalog), and we ourselves, as well as Bellett fans across the country, felt very disappointed by this, so this month we decided to try the Yatabe test again just to measure the speed. The test car was the same, but its carburetors were overhauled and the distributor was replaced, among other adjustments.

This time, we estimate our test results to be the true average performance one can expect for a completely stock GTR. Even in third gear, it could easily reach 7000rpm, and at top speed in fourth, it was just over 6000rpm. The C/G top speed test is carried out by continuously driving at full throttle around the 5.5km circuit at Yatabe, measuring both the time required for the flat 1km section on the two long straights, and the overall 5.5km lap time, including the banked turns at each end. On this day, the south wind was blowing at a maximum of 4m/s and an average of 2m/s. The best speed on the 1km straight line was 182.0km/h, and the speed on the side that was negatively affected by the wind was 179.1km/h. Due to the running resistance of the banking and the fact that there was a section where the wind was blowing directly against us (although there was also a tailwind when driving the opposite direction), the average speed for the 5.5km lap was a consistent 179.0km/h. The engine speed at this vehicle speed was 6050rpm in the section where it was the highest, and at its lowest it never dropped below 5900rpm.

The tachometer was, as usual, a little lenient, as was the speedometer. At the top speed, when the actual speed was about 180km/h, the car’s speedometer indicated 195km/h. Although the accuracy of the tachometer could not be measured, it read about 5% lower than the estimated value from the power performance chart (calculated value, not considering the change due to the centrifugal force of the tire diameter). Even considering the increase in tire diameter, it seemed that the displayed engine speed was slightly lower than the actual speed. The standing-start acceleration times were almost the same as the data from last month’s test. However, when starting off the line, the engine would lurch wildly enough on its mountings to hit something in the car’s body the moment the clutch was quickly engaged, making clean starts difficult. This phenomenon did not occur when we tested the car last month, and as a result, the acceleration time from 0-400m was 0.1 second slower than before. On the other hand, performance after shifting into third and fourth gears improved due to the engine’s better performance, so the 0-1000m acceleration time actually improved by 0.2 seconds.

To summarize what was confirmed in the second test, the 1600GTR’s power performance–a top speed of 182.0km/h and a 0-400m time of 16.8 seconds–is still at the cutting edge of 1.6-liter GT coupes in the world today. When compared to cars in the same class with similar 1.6-liter DOHC engines, the results are as follows: Bellett GTR, 179.0km/h maximum speed, 0-400m in 16.8 seconds; GTO MR, 182.0km/h maximum speed, 0-400m in 16.3 seconds; Celica GT, 176.8km/h maximum speed, 0-400m in 16.8 seconds. Needless to say, the other two cars are equipped with five-speed gearboxes, while the Bellett has the disadvantage of a four-speed, but the Bellett is smaller and lighter, which helps make up the difference. Of course, the overall compromises of the small body, such as roominess (especially in the rear seat), noise level, and ride comfort are considerable disadvantages by modern standards, but this is inevitable considering the age of the design.

The condition of the GTR’s engine remained constant throughout the test period. Even when the car was kept at top speed and repeatedly lapped for more than 10 minutes, the water temperature remained constant at 85°C, although the oil pressure dropped slightly. Still, extended cruising at 160km/h (about 5600rpm) showed all readouts well within the safe range. In addition, the air pressures in the Yokohama GT Special XX 165HR-13 tires, which started out at 1.8kg/2.1kg, and had risen to 2.0kg/2.4kg immediately after the speed test, also stayed within the normal range.

Postscript: Story Photos