Isuzu 117 Coupe EC (1970)

Publication: Car Graphic

Format: Road Test

Date: June 1970

Author: Shotaro Kobayashi

Road testing the Isuzu 117 Coupe EC

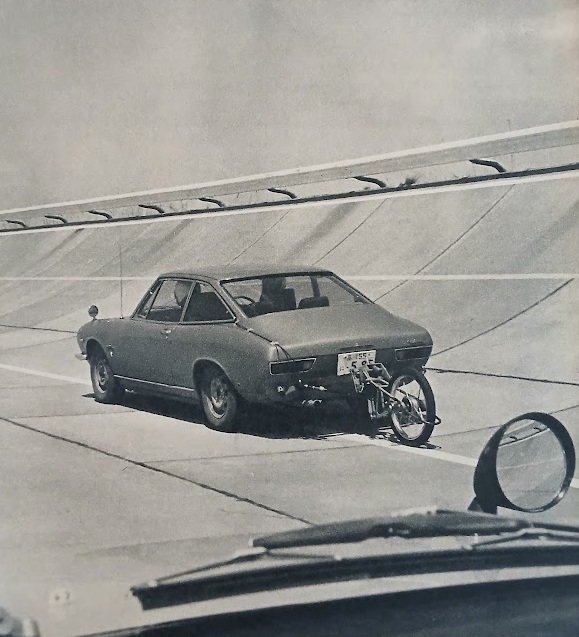

The Isuzu 117 Coupe, which combines a flowing Giugiaro-designed coupe body with Isuzu’s well-regarded 1.6-liter DOHC engine, first appeared in a form producing 120ps at 6400rpm with twin Solex carburetors. In the autumn of 1970, however, two further variants were added to the range: the EC and the 1800. The EC enhances the 1.6-liter DOHC engine with the fitment of a Bosch-patented electronically controlled fuel-injection system, while the 1800 is a model aimed towards a broader audience, powered by a 1.8-liter SOHC engine with twin SU carburetors, producing 115ps at 5800rpm. Prices are 1.47 million yen for the 1800, 1.67 million yen for the carbureted 1.6-liter model, and 1.87 million yen for the 1.6-liter EC. The car tested this time, over three days at Yatabe and elsewhere, was the fuel-injected 117 Coupe EC.

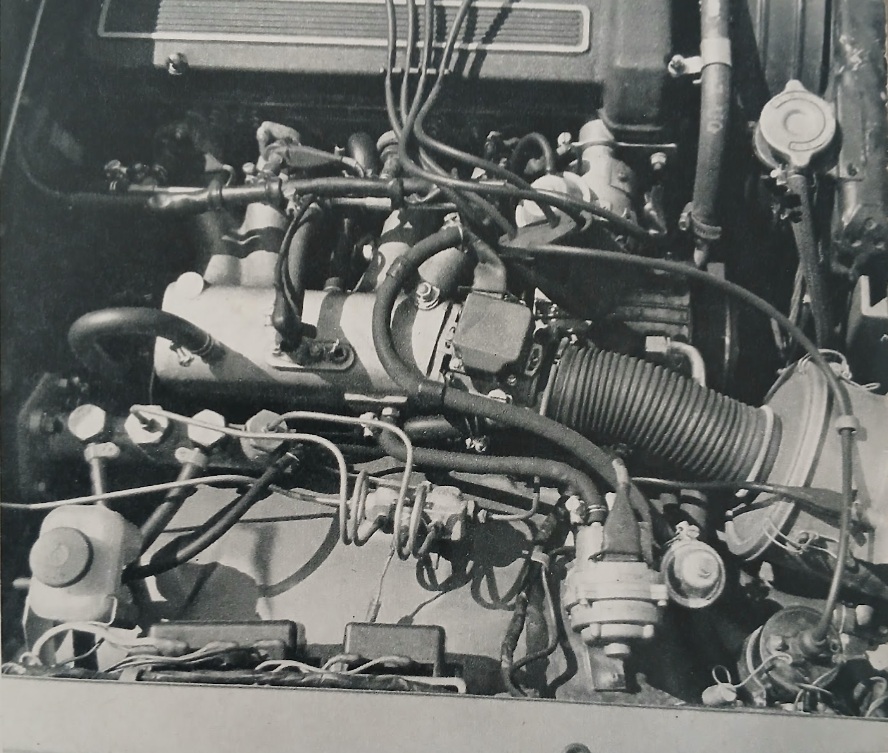

Fuel injection can be said to have several advantages, but the most important one lies in the fact that the quantity of fuel injected is precisely measured by means of electronics. Strictly speaking, it would be more accurate to say that injection time is controlled, since it is the opening duration of the injector nozzle that varies. This makes it easier to control exhaust emissions without sacrificing performance. Other benefits include increased output due to the absence of the flow restriction inherent in a carburetor venturi, the convenience of an automatic choke, and simpler routine maintenance.

The 117 EC’s electronically controlled Bosch fuel-injection system is identical to that used in the Volkswagen 411E. Although the compression ratio remains the same as that of the carbureted version at 10.3:1, output rises from 120ps/6400rpm to 130ps/6600rpm, while torque increases from 14.5kgm/5000rpm to 15.0kgm/5000rpm.

To summarize the system’s construction briefly: fuel is delivered by a pump to a pressure line, where it is kept at a constant 2kg/cm² by a pressure-control valve. Each injector nozzle, mounted in the intake port, incorporates a solenoid-operated valve, which is actuated by electrical pulses from a control unit located inside the cabin on the left side of the front seat. By varying the duration of these pulses, the injection time–and thus the injected fuel quantity, since pressure is held constant at 2kg/cm²–is controlled. Injection quantity is basically determined by engine speed and load, but additional fuel is supplied during cold starting, warm-up operation, and acceleration.

The four injectors are divided into two groups, cylinders 1 and 3, and cylinders 2 and 4, and injection is carried out by group. Injection occurs at top dead center of the intake stroke of cylinders 1 and 4. As a result, fuel for cylinders 3 and 2 is injected while their intake valves are closed, and is only drawn into the combustion chamber together with air when the valves subsequently open. In this system, however, combustion is relatively insensitive to injection timing, so in practical use this presents no problem.

Aside from the adoption of fuel injection, the 117 Coupe remains largely unchanged from the time of its debut. When C/G tested the car in our New Year 1969 issue, we wrote that “when power performance, handling, ride comfort, and accommodation are all considered as a whole, we can say that the Isuzu 117 ranks at the very top of the world’s 1600cc-class four-seat coupes.” Returning to the car today, after an interval of three and a half years, we must candidly acknowledge that in several respects it has already been left behind by the prevailing trends.

Morning cold starts are entirely foolproof. Turning the ignition key first brings the continuous operating sound of the electric rotary pump from the rear; there is no choke knob, and simply engaging the starter brings the engine to life immediately. Initial fast idle is set at around 2000rpm, and within a few minutes it settles naturally to a slightly uneven idle of about 1200rpm. On the test car, the throttle cable occasionally caught at around 2000rpm, and after high-speed running on the expressway–such as immediately after arriving at a toll gate–the engine speed would sometimes hunt up and down between 1000-2000rpm, even with the throttle held steady, as though it were being lightly blipped. Aside from this tendency, the engine ran extremely well: throttle response was instantaneous, and in the lower gears it pulled up to 8000rpm without hesitation. As far as power performance is concerned, the 117 Coupe can still be said to rank among the world’s best in its class.

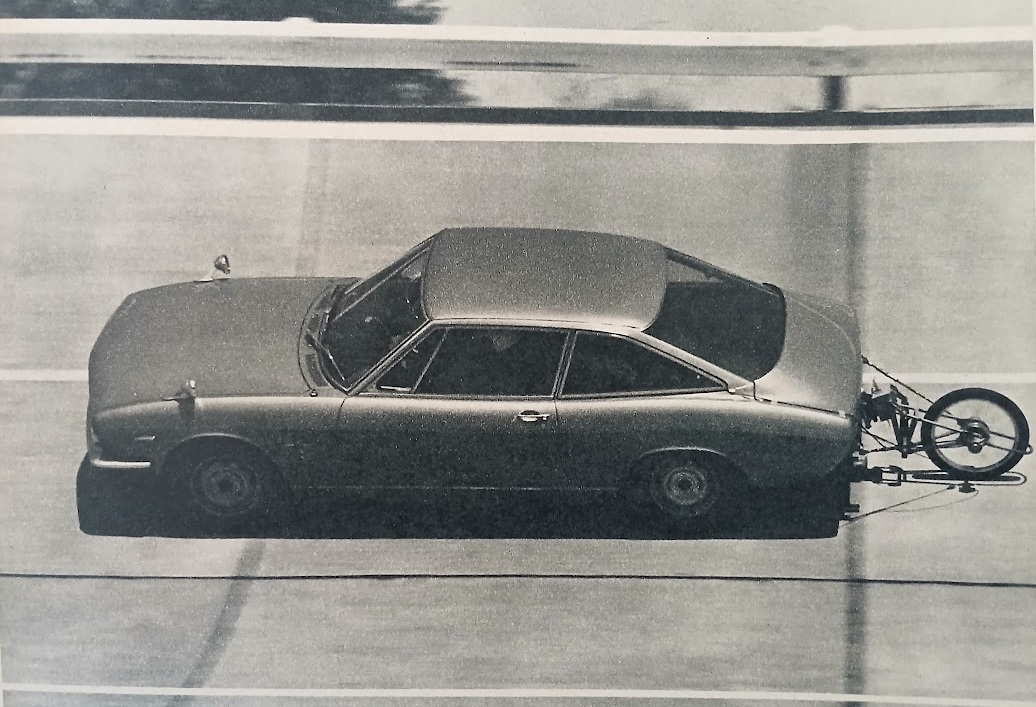

At Yatabe, top speed averaged 180.9km/h over the 1km straight, and exactly 180.0km/h per lap on the 5.5km circular course. The instruments were optimistic: the speedometer indicated 188km/h and the tachometer 6800rpm, even though the calculated engine speed should have been around 5900rpm. Two final-drive ratios are available for the 117 Coupe, 3.73 and 4.11, and the test car was equipped with the shorter (numerically higher) ratio. The tachometer is marked with a yellow zone from 6400-7000rpm and a red zone from 7000-8000rpm. The top speed of 180km/h therefore arrives well below the red zone, just around the point of maximum output, and leaves ample margin in both intake and exhaust efficiency and in the valve mechanism itself. With a favorable tailwind, it gave the impression that another 5km/h could be easily achieved.

The engine’s minimal vibration at all engine speeds is particularly noteworthy. Mechanical noise remains very subdued up to about 4000rpm; beyond that it can no longer be described as especially quiet, though it is not intrusive, either. Even so, whether cruising effortlessly at 150km/h (so long as there are no strong crosswinds) or running at an absolute maximum, the overall noise level inside the cabin is low, and there is no sense whatsoever of the engine being strained.

Regrettably, however, the test car exhibited a vibration from somewhere in the driveline (not in the engine itself) above 120km/h, eventually drawing complaints from the rear passengers. The vibration was not felt through the steering wheel, and it did not disappear when the clutch was disengaged, ruling out the engine. The most likely causes are thought to be rear-wheel imbalance or the propeller shaft. (The same phenomenon was observed in the 117 tested in our January 1969 issue; this suggests that the cause may be the design of the propeller shaft. The 117 uses a two-joint shaft, whereas other cars in this class now commonly employ a two-piece, three-joint design.)

Acceleration performance, which was outstanding at the time of the car’s debut, is no longer startling when viewed against today’s higher standards. Standing-start acceleration figures are as follows: 0–50m in 4.8 seconds, 0–100m in 7.6 seconds, 0–200m in 11.2 seconds, 0–400m in 17.8 seconds, and 0–1000m in 32.5 seconds. Comparing 0–400m times with other cars in the same class, the 117 Coupe trails the Celica GT (16.8 seconds) and the Galant GTO MR (16.3 seconds), but matches the Alfa Romeo Giulia GTV (17.7 seconds, according to overseas sources) and the Fiat 124 Coupe 1600 (17.8 seconds). In this sense, it remains fair to say that the 117 is still among the top performers in its class worldwide.

The 117 Coupe’s engine has long been known for its exceptional tractability, an unusual strength for a high-performance DOHC unit, and this characteristic is even more pronounced in the fuel-injected version. Third gear, in particular, stands out: the time required to accelerate through each 40km/h increment from 20km/h up to 120km/h is consistently in the eight-second range: 8.8 seconds from 20-60km/h, 8.2 seconds from 40-80km/h, 8.1 seconds from 60-100km/h, and 8.9 seconds from 80-120km/h. Only when the speed range rises to 100-140km/h does the time stretch to 11.0 seconds.

Even in top gear, gentle throttle application from as low as 40km/h produces smooth acceleration with no trace of knocking, and beyond 120km/h the engine continues to respond clearly. Thanks to this flexibility, the 4-speed gearbox presents no practical shortcomings in everyday use. Nevertheless, for a car in this class today, one cannot help wishing for a 5-speed transmission. Overtaking performance would naturally improve, and high-speed cruising would become even quieter. By the same token, the absence of an automatic transmission option at this price level feels like an omission, particularly when the related Florian is available with a Borg-Warner 3-speed automatic.

Fuel consumption over the full test distance of 986.8km averaged 6.9km/l (odometer corrected; the indicated distance was 3.0% optimistic). The worst figure, 6.10km/l, was recorded over 222.7km including the constant-speed tests at Yatabe, while the best result–7.35km/l–was achieved during high-speed touring on the Tomei Expressway and around Hakone.

We were unable to measure constant-speed fuel consumption at Yatabe, as our unfamiliarity with fuel-injection systems worked against us. Because the fuel delivery rate per unit time is constant and unused fuel is returned to the tank, we attempted to measure consumption by fitting fuel meters at both the inlet and return lines and calculating the difference, but for reasons that remain unclear this method did not produce reliable results. As a result, we must instead present the manufacturer’s measured figures, compared with those of the carbureted 117 Coupe: 18.0km/l for both cars at 40km/h, 16.5km/l (16.0 for the carbureted version) at 60km/h, 15.0km/l (13.0) at 80km/h, 12.5km/l (11.0) at 100km/h, 10.5km/l (9.0) at 120km/h, and 9.0km/l (7.5) at 140km/h.

At low speeds up to about 60km/h, the two cars’ fuel consumption is about the same, but from 80km/h upward the difference becomes clearly significant. Even so, to recoup the initial price gap of about 200,000 yen through fuel savings alone would take at least 30,000km. The fuel tank is large, at 58 liters, and a warning lamp comes on when the remaining amount drops to about 8 liters.

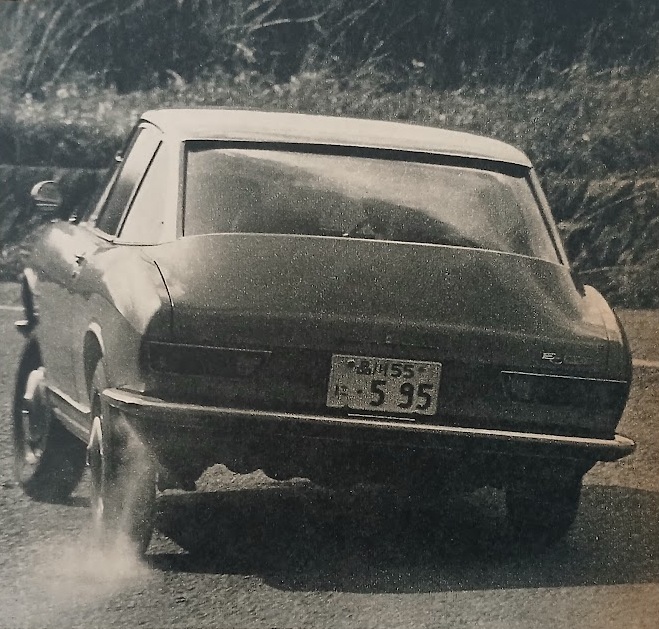

The place where the 117 Coupe’s age is most noticeable is its handling. Even today the 117’s handling is by no means bad; for a car with a conventional suspension it remains at a high level. But it feels like a model from a previous era. The first corner caught us by surprise because the steering was unusually heavy. We immediately suspected low tire pressure and checked, but they were correctly set at the specified 1.8/1.8kg/cm² for high-speed driving. In any case, the steering is unjustifiably heavy. This was not something we remembered from our test three and a half years ago, so we hope it is a problem specific to the test car.

The steering is not only heavy at low speed; at high-speed corners the force required to hold a steady angle is also disproportionately high for the vehicle’s weight. In short, the car understeers excessively. The tires, Dunlop Grand Speed GS-1s in size 6.45H-14-4PR, have high lateral rigidity and are quite stiff, so they do not squeal easily even in fast cornering. The steering takes three turns lock-to-lock and feels very slow; in hard corners, it requires decisive, forceful inputs to change direction. Still, while the understeer is excessive by any standard, the handling is not bad overall. When a corner is taken at full power, the inside rear wheel tends to lift and the tail gently steps out into oversteer, but the limit speed is unusually high for a live-axle car. Even if you abruptly close the throttle mid-corner, its cornering attitude does not change at all. This may be far from what enthusiasts prefer, but it is an undeniably safe handling characteristic. On rough roads, kickback is well absorbed through the steering, yet its feel is not so numb that the driver loses all sense of the surface.

As the pronounced understeer suggests, directional stability at high speed is excellent, but the car is surprisingly susceptible to crosswinds. On the Tomei Expressway the winds were blowing so strongly that the wind socks stood up horizontally, and the 117 Coupe required constant concentration at a steady 140km/h. In particular, when we caught up with a car ahead and immediately closed the throttle, the car showed a clear tendency to yaw lightly and oscillate two or three times (this was while driving in a straight line with three occupants). With an independent suspension, such behavior might be understandable, but in the 117 with its live rear axle there is no obvious reason for this, so the behavior is puzzling.

Ride comfort is remarkably good considering the live rear axle. Naturally, the suspension is tuned on the firm side for high-speed driving, but even at low city speeds, running over tram tracks and the like, the shocks are heard more than felt, and the ride remains exceptionally smooth. In this respect it is certainly superior to the Alfa, Fiat 124 Coupe, and Galant GTO MR. The live axle is noticeable only when driving hard over very rough surfaces. Although the car appears low, ground clearance is a generous 180mm, so the car can be driven confidently over rough roads, although this subjects rear-seat passengers to significant vertical tossing. Body strength and rigidity feel extremely high, and even under such severe treatment no abnormal creaks or signs of deformation were detected. Noise from the suspension is also well suppressed.

The brakes are very good. The servo-assisted disc/Alfin drum system is relatively light to operate, and braking force builds progressively in proportion to pedal pressure. Applying 28kg of pedal force from 50km/h resulted in deceleration of 0.92g. The disc circumference is fitted with a steel ring to prevent squeal–an elaborate measure that is completely effective. In the 0-100-0 fade test, initial pedal effort was 18kg; from the seventh stop this increased to 25kg, accompanied by a smell of heat, but it did not rise further, and the braking effect remained stable. After driving at high speed for three minutes, the brakes recovered completely.

Driving position is, of course, a matter of personal taste, but our consensus was that the bodywork is too low and the driver sits relatively too high in relation to the steering wheel and scuttle. On the other hand, outward visibility is exceptional, and the beautifully arranged gauges on the wooden instrument panel are easy to read, without obstruction from the steering wheel. The seat shape and cushion firmness are appropriate, and even after long periods behind the wheel one does not feel unduly fatigued. However, the inertia-lock seatbelts have a considerable amount of slack before they lock, so one cannot help but worry whether they would hold the body securely in an accident (tightening them enough to remove the slack makes them uncomfortable). The layout of the controls is generally adequate, but the frequently used lighting and wiper switches are a rather long reach when seated comfortably. Rear-seat space is somewhat tight for two adults on a long trip.

Headroom is minimal: with the front seatback set roughly in the middle of its angle adjustment range, the driver’s head comes very close to the roof. Rear headroom can be improved somewhat by reclining the rear seatbacks (which can be adjusted in three stages), but doing so makes the legroom even more cramped. In this respect, the Toyota Celica GT, Galant GTO, and Fiat 124 Coupe, whose overall dimensions are nearly identical, offer more space.

The interior finish is on par with that of a high-grade British sports saloon, and the accessories are comprehensive. One feature that proved genuinely convenient in daily use was the stepless speed adjustment for the wipers; by turning the switch in the opposite direction, they can also be set to intermittent operation. However, because the blades are not a finned type, they lift off the windshield and become ineffective above about 120km/h. The rear window, of course, has a defogger (with printed wiring) which proved extremely effective. The ventilator is weak by today’s standards, and even in the mild April climate it became hot in the rear seats. In summer, the optional (195,000 yen) factory dash-mounted air conditioner would be essential–the test car was so equipped.

Even taking into account that this is a low-volume luxury model, the price of 1.87 million yen must still be regarded as disproportionately high. But apart from the unreasonably heavy steering, the 117 remains a well-balanced sporty coupe, and although it has become somewhat dated overall, it will surely be cherished for many years by buyers with conservative tastes.

Postscript: Story Photos