Honda 1300 Coupe 9S (1970)

Publication: Car Graphic

Format: Road Test

Date: April 1970

Author: “C/G Test Group” (uncredited)

Summary: A highly practical five-seater coupe based on the 1300 sedan. Roominess not inferior to the sedan. Air-cooled engine with four carburetors. Exceptional power. Stiffer unibody construction and suspension than the sedan, chassis finally catching up with the engine. Maneuverability significantly improved over the sedan.

Road testing the Honda 1300 Coupe 9S

When we tested the Honda 1300 77 in the February issue, we were highly impressed by its excellent engine, but concluded that its chassis was too soft to keep up with it, and criticized the car for being unable to safely utilize its great power performance. The 77 Deluxe we tested for that report was a very early production model (chassis number H1300-1000611) that was purchased by C/G for long-term testing, and during the approximately 2,000km that we had driven it at that point, it had given us frequent trouble, so the enthusiasm we had initially felt for the Honda 1300 gradually faded.

Later, as mass production progressed, we began to hear people say that the Honda 1300 had improved considerably, but when we occasionally borrowed one to drive, we couldn’t find any improvements significant enough to convince us.

However, after testing the recently released Coupe 9, our opinion of the Honda 1300 has been significantly revised. In short, the handling of the Coupe 9 has improved to a degree beyond what we could have imagined from the C/G 1300 77 sedan, to the point that it feels like a completely different car.

According to user reports, the Honda 1300 seems to exhibit a great deal of variation from one example to the next, so it is dangerous to judge the whole series based on the experience of driving just one car. So, in the case of the Coupe 9, we drove both the Deluxe and S models (which are identical mechanically, differing only in interior equipment), and since both showed similar behavior, it seems that the skeptical C/G test group has finally been convinced.

There are two 1300 Coupe models: the Coupe 7, which is equivalent to the 77 sedan, with a single carburetor, and the high-performance four-carburetor Coupe 9, each of which offers variations in the interior and trim. We drove the Coupe 9 Deluxe and S models, but since it was the S that was tested at Yatabe, this report will mainly cover that model (as mentioned above, all Coupe 9 models are mechanically the same).

In the February test of the 77 sedan, our main criticism was around handling and stability: simply put, the suspension was too soft for the car’s speed potential, and in combination with the feeble standard tires (6.2S-13), the result was excessive understeer in corners, which could be dangerous.

As soon as we rounded the first corner in the Coupe 9S, we sensed that the steering response was much better and the degree of understeer was greatly reduced. At Yatabe we carried out slalom runs at 130-140km/h, weaving left and right, and found that body roll was far less pronounced than with the sedan, with the car faithfully following steering inputs. Although the steering still falls well short of the sharpness one might expect from a rack-and-pinion mechanism, it is at least accurate enough that an average driver can steer at high speeds without concern (in the case of the sedan with its standard tires, there is a large time lag between the driver’s steering inputs and the actual steering effect). Also, in the cornering test on the skid pad, the Coupe is much less prone to becoming a “three-wheeler” than the C/G 77 sedan. Even when pushed near the limit where the inside rear wheel lifts off the ground, the front wheels still have enough cornering power to remain under control. The tendency to cut inward when the throttle is released during cornering is also less severe than in any other Honda 1300 sedan we have driven. In short, the handling characteristics that are often regarded as the negatives of front-wheel-drive have been largely reduced in the Coupe 9S, and instead the advantages of front-wheel-drive are brought to the fore.

What is the key to this remarkable transformation of the Honda 1300? First of all, it is the tires. The test car was fitted with Dunlop GS1 6.2H-13 tires, which, as we noted in the February issue’s road test, also completely transformed the handling of the C/G 77 sedan. Although the tire is of four-ply construction, its stiffness is essentially equivalent to that of six-ply tires, and its high sidewall rigidity is thought to be particularly well-suited to the Honda 1300, which carries a heavy load over the front wheels. Next is the design of the coupe’s suspension. There are slight differences in the rear suspension between the coupe and the sedan. In the sedan, the “cross beam” axle and the leaf springs are connected by what is called a floating joint, consisting of two vertical pins and shackles. Because the axle oscillates about these pins as its pivot, the springs are subjected only to vertical loads, and no other forces act upon them. In the coupe, the lower of the two pins in this floating joint has been eliminated, and the axle now oscillates about a single upper pin. This means that the springs are required to accept a certain amount of torsion, but as a result the lateral rigidity of the rear suspension is slightly increased. The damper settings also differ between the 7 and 9 (as they do between the 77 and 99 sedans): the damping force of the 7 is 40kg on the extension side and 10kg on the compression side, while the 9 is 50kg and 20kg, respectively. Finally, the coupe has a lower center of gravity than the sedan. Taken together, we think it is the combination of these factors that is responsible for the 9S Coupe’s very good handling and stability, especially when compared to the 77 sedan.

The Coupe 9’s ride feels firm, but this is likely due in part to the psychological effect of the tire noise. It is certainly firmer than the 1300 77 sedan, and does not “float” even when going over undulating surfaces at high speeds (the C/G 77 is prone to pitching in such situations). The tires feel as if they are overinflated, clearly picking up joints in the pavement with a sharp, “kotsu-kotsu” sound (although not as much as with radials). However, the ride is still very comfortable on all kinds of road surfaces. Small irregularities are absorbed well by the suspension, and are mostly heard as tire noise rather than felt. The ride is also excellent on rough roads, and directional stability is not easily affected by the road surface, allowing the driver to maintain a high average speed on unsealed surfaces. Power is ample, and we discussed that with just the addition of sump guards, this car could do very well in rallies even in stock condition.

The adhesion of the Dunlop GS1 6.2H-13 tires was found to be very high both in tests on the skid pad and during hill climbing. Even when powering around tight corners in second gear, there was very little wheelspin, and once the tires gripped the road, the engine’s plentiful low-speed torque immediately delivered powerful acceleration. The 1300 Coupe is an ideal hill climber.

Downhill driving, on the other hand, demands real caution. Even at the best of times, the weight distribution of a heavy front-wheel-drive car becomes least favorable when braking on a descent. If you accidentally enter a corner at too high a speed and then brake (often with a considerable amount of steering lock already wound on), the tires will scrub straight ahead, leaving you with virtually no control at all. With the Coupe 9’s better tires and somewhat firmer suspension, the danger is greatly reduced compared to the 77 sedan, but it still demands respect and restraint due to the car’s high speed potential (this is not limited to the Honda, but is true for all powerful front-wheel-drive vehicles).

Last December, the Honda 1300’s engine received revisions to increase low and mid-range torque and improve overall drivability. The camshaft was changed to have less overlap, and the ignition timing was also revised, reducing output in the 99 model by 5ps to 110ps/7300rpm. Maximum torque was also reduced to 11.5kgm/5000rpm, but the torque curve became flatter and more usable. Naturally, the Coupe 9 uses the same revised 110ps engine.

Those who buy this coupe because they are attracted to Honda’s reputation for speed will be more than satisfied. To cite some figures, it recorded an average top speed of 171.4km/h on the 1km straight at the Yatabe test course, and 169.1km/h on the 5.5km circuit course. The instantaneous top speed achieved with the fifth wheel attached reached about 173km/h. It also consistently recorded 0-400m acceleration times of 17.5 seconds. All measurements were taken with two occupants on board, about 40kg of test equipment, and a full tank of fuel.

On recent Honda 1300 engines, a very simple over-rev prevention device is built into the distributor in which centrifugal force causes the rotor terminal to catch, preventing the ignition spark from firing. In the case of the Coupe 9, this prevents the engine from revving above 7500rpm (the start of the red zone on the rev counter). By contrast, the C/G 77 sedan, which does not have this device, revs willingly beyond 8000rpm, and even at that speed the valve gear continues to follow perfectly. As such, the limiter on the Coupe 9 is clearly a concession to durability.

There is little need to restate here the excellence of the Honda 1300 engine. Even for those of us who are thoroughly familiar with this engine from the C/G 77 sedan, driving the Coupe 9 for the first time brings a fresh sense of admiration: its absolute power, and the immediacy of its throttle response, make a strong impression. It is turbine-smooth over a wide range of revolutions, to a degree that is hard to believe for a reciprocating four-cylinder engine. It is often said that the Honda 1300 engine is quieter at high speeds than many water-cooled engines. In this Coupe 9, as well, there is none of the “dry” noise that is characteristic of air-cooled engines. However, the noise level was a little higher than in other Honda 1300s we have driven, and from around 4000rpm, a strong-sounding “power roar” began to build and resonate inside the cabin.

Power is more than ample throughout the rev range, so whenever you press the throttle, the car responds instantly with decisive acceleration. When you find a small gap in traffic on a national highway and want to quickly overtake a line of cars, this extra power is invaluable, making a genuine contribution to what Honda calls “active safety.” Acceleration in third gear, in particular, can only be described as “lavish.”

Compared to the C/G 77 sedan, the difference in power between the single-carb and four-carb engines is especially evident in top-gear acceleration above 100km/h. For example, the acceleration time from 60 to 100km/h is 10.2 seconds for the Coupe 9 (11.9 seconds for the 77 sedan), 10.3 seconds (12.2 seconds) from 80 to 120km/h, and 13.5 seconds (19.0 seconds) from 100 to 140km/h. The latter figure is a full 5.5 seconds faster than the 77 sedan. On the other hand, standing-start acceleration is not dramatically faster than the 77 sedan (the 0-1000m time, for example, is 34.8 seconds for the sedan and 32.6 seconds for the Coupe). This is likely due to the ignition cut-off limiting the Coupe’s engine speed to 7500rpm.

At Yatabe, the aforementioned instantaneous top speed of 173km/h was achieved at 7450rpm, coinciding almost exactly with the maximum allowed by the engine’s limiter. On one or two occasions, by taking advantage of a slight downhill gradient (such as the exit from the banking), the needle appeared to edge past 7500rpm, at which point the engine felt like it was on the verge of cutting out. Simply put, unless this cut-off is removed, it will be impossible to achieve the manufacturer’s claimed top speed of 185km/h, no matter how favorable the tailwind.

On the other hand, one of the Honda’s favorable characteristics is that its power holds up well even at low speeds. Anyone familiar with Hondas knows their reputation for high engine revolutions, and most are tempted to let the tachometer needle spin through its full range in each gear. However, the 1300’s engine is flexible enough that it can accelerate smoothly from under 40km/h (about 1700rpm) in top gear, and once this is learned, you can drive quickly and quietly using only low revs.

Surprisingly, this four-carburetor 110ps coupe returned better fuel economy overall than the C/G 77 sedan. This was true even at constant speeds, and especially clear when driving at a steady 100km/h on the highway. The C/G 77 sedan has never managed to reach 10km/l when measured on the Tomei Expressway, but the Coupe 9 recorded 12.5km/l under the same conditions. It was also slightly more economical than the C/G 77 in urban areas, reliably returning 6.5 to 7.5km/l. It should be noted, however, that the 77 uses regular-grade gasoline, while the Coupe 9 requires super.

In the test report for the 77 sedan, we pointed out its poor warm-up characteristics after a cold start, but starting with 1300s produced in December 1969, a system was installed that draws in warm air heated by the exhaust manifold. The test Coupe 9 was also fitted with this device, and it proved highly effective. The engine settled into a smooth idle immediately after a cold start, and pulled powerfully as soon as it moved away from rest.

The coupe’s front brakes differ from the sedan’s in that the calipers are a Sumitomo three-piston type. The servo is also stronger than in the 77, so that rather than requiring a deliberate push, simply resting the weight of your foot on the pedal applies about 0.3g of deceleration (about the same as a normal stop in city driving). With the coupe’s stiffer suspension and slightly better weight distribution, there is relatively little nose dive when braking compared to the sedan. In the 0-100-0 test, pedal force only increased from 15kg on the first stop to 22kg on the tenth, so the brakes can be considered safe for repeated use at high speeds.

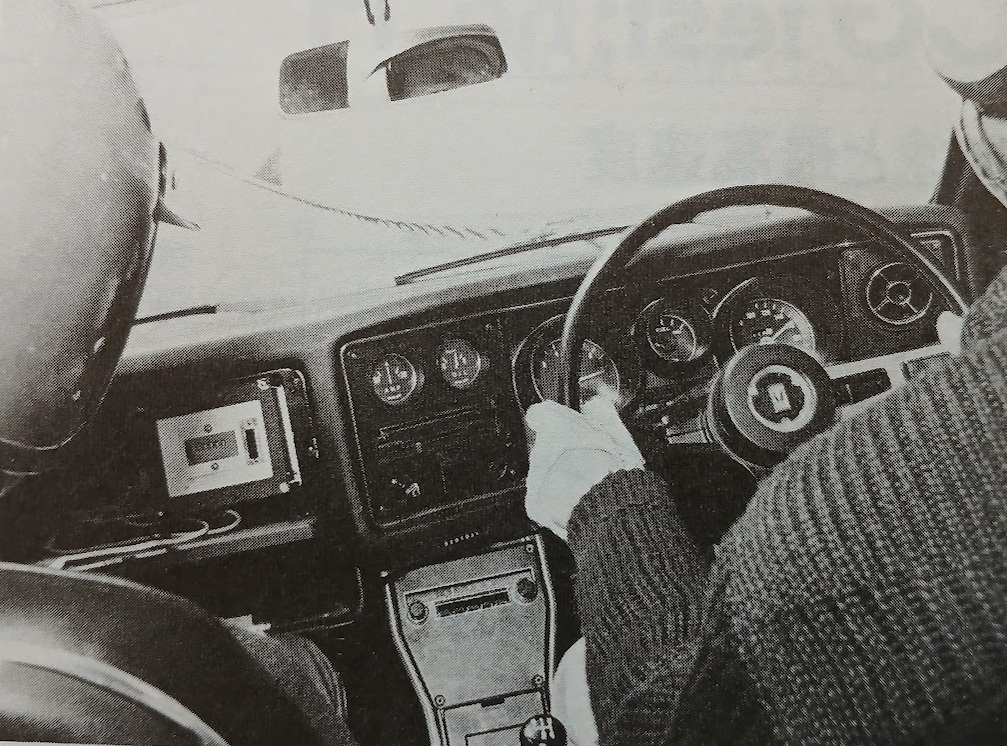

Compared with the sedan, the coupe’s lower overall height is accompanied by a slightly more reclined steering column, and the marginally larger-diameter steering wheel sits correspondingly lower. As a result, the driving position feels much more natural than that of the sedan. The instrument panel, known as the “flight cockpit,” is a little ostentatious in concept, but all the gauges are larger and easier to read than in the sedan, both day and night. The seat upholstery looks like leather at first glance, and it feels softer and more comfortable than that in the sedan. The rear floor is flat, so three people can sit comfortably in back. The accommodations are more like that of a two-door sedan than a coupe, and the high window sills front and rear provide a moderate amount of privacy and a sense of protection. Driving over rough roads revealed that body rigidity, especially in the rear section, is higher than that of the sedan. The interior finish is also generally acknowledged to have improved markedly compared to early production cars.

When it comes to styling, opinions naturally vary, but this Honda 1300 Coupe, which resembles a miniature Pontiac GTO, attracted attention wherever it went.

After testing the Coupe, we were left with the conclusion that Honda made two important mistakes with the 1300: first, the 1300 sedan was brought to market too early, and second, the coupe was brought to market too late.

Postscript: Story Photos