Honda 1300 77 Deluxe (1970)

Publication: Car Graphic

Format: Road Test

Date: February 1970

Author: “C/G Test Group” (uncredited)

Summary: Air-cooled four-cylinder, powerful, smooth up to 8000rpm, low noise level even at high revolutions, power performance comparable to a 1600cc GT, poor fuel economy, unsettled handling a cause for concern, unsatisfactory heater and demister.

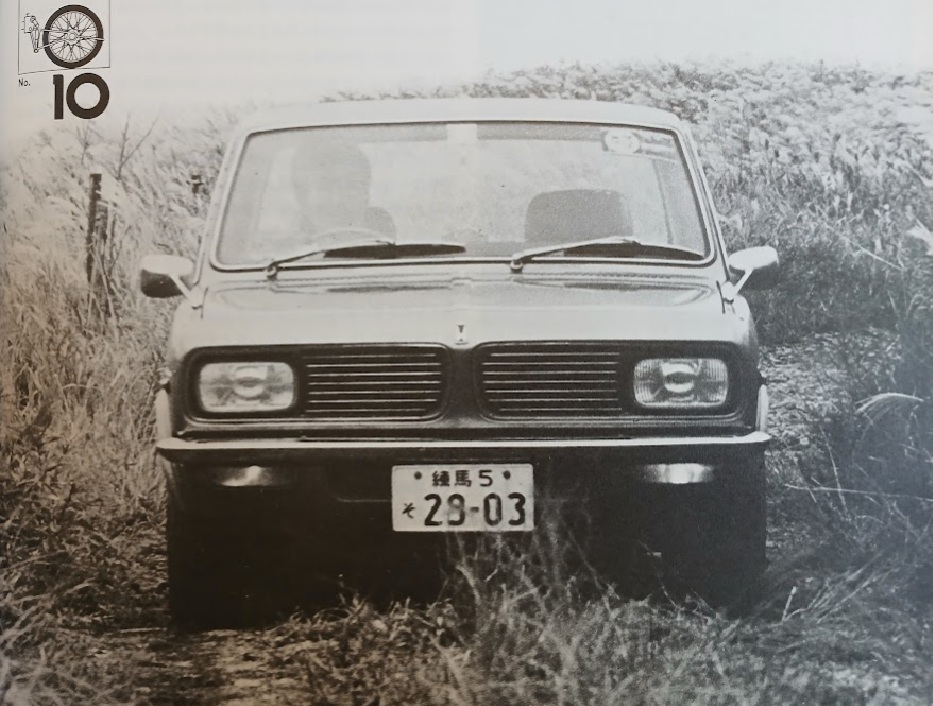

Road testing the Honda 1300 77 Deluxe

Few cars have been as controversial in recent years as the Honda 1300. Technically, it is an ambitious design that features a powerful, double-wall air-cooled, dry-sump lubricated four-cylinder engine, mounted transversely and driving the front wheels, following in the footsteps of the ill-fated Honda F1 racing car, the RA302, and has attracted the attention of engineers both in Japan and abroad. However, for the first two or three months after its release on April 15 last year, the Honda 1300 was rarely seen on the streets. At the time, the automotive world was abuzz with the issue of defective Honda cars, and dark rumors were circulating that the 1300 might also be caught up in the scandal. (In reality, it was said that the measures to deal with the “defects” in the N360 had disrupted the production plans for the 1300, as the design staff and factory personnel were temporarily diverted to that role.)

C/G placed an order for a Honda 1300 77 Deluxe as soon as it was announced, but for the reasons mentioned above, delivery was delayed, and by the time it was finally delivered in mid-June, the editor in charge of road testing had been seriously injured and was in the hospital. We earnestly wanted to test the 1300 as early as possible and report on it in full detail in the magazine, so we would like to firstly apologize for the six-month delay due to unavoidable circumstances.

The car reported on in this road test was the early production model that C/G purchased for long-term testing, and we have already driven it about 12,000km. As you know, Honda products are subject to frequent design changes, especially in the first few months after mass production begins, so it’s quite possible that there are some differences in design and behavior between the C/G 1300 and the latest model. We have tried to mention any differences we noticed in this report, but we would like to point out in advance that there may be some that we have overlooked (although according to the manufacturer, there have been almost no changes in the specifications).

Those who are attracted to the Honda 1300 are probably most concerned with speed, so let’s start there. The C/G 1300 recorded a top speed of just 160.0km/h and a 0-400m acceleration time of 18.5 seconds with two passengers and test equipment aboard (the equivalent of a nearly full load). This performance is almost comparable to the Alfa Romeo 1300GT and Bluebird 1600 SSS, but is still not as fast as the manufacturer claims (according to the catalog, top speed is 175km/h, and the 0-400m time is 17.5 seconds).

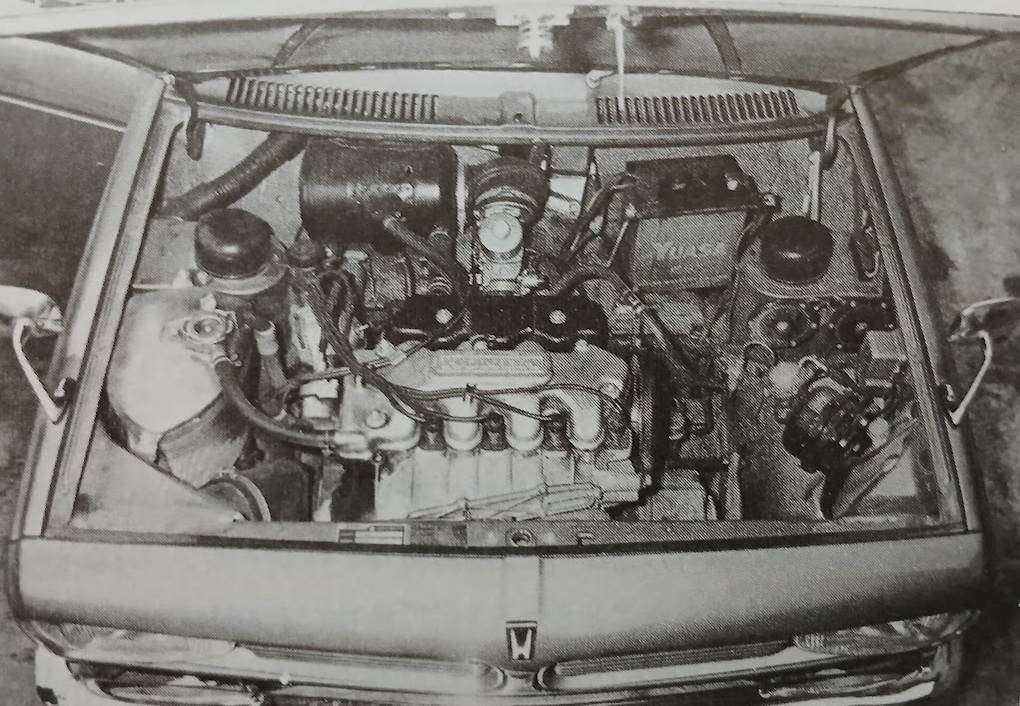

Like all Honda products, the power unit takes precedence over everything else, occupying a central position in the design of the 1300. As mentioned above, it is a forced air-cooled, SOHC four-cylinder, fundamentally the same as the air-cooled F1 RA302, and employs a transversely mounted, front-wheel-drive layout pioneered by the BMC Mini. As usual for a Honda engine, it is a high-revving, high-output type, its 100ps/7200rpm being about 30% higher than the average for a 1300cc class practical car (the maximum torque of 11.0kgm/4500rpm is about standard for this class).

Now, if you were to drive the Honda 1300 without any prior knowledge, you would never believe that it was air-cooled. The “dry” noise peculiar to air-cooled engines is not audible throughout the entire rev range, and the sound of the cooling fan does not suddenly increase at high revolutions (like with normal water-cooled engines). The Honda 1300 has brilliantly overturned the conventional wisdom that air-cooled engines are noisy. At 100km/h, the engine is only humming along lightly, and is less noticeable than the wind noise around the windowsills. What is particularly noteworthy is that the noise level does not increase exponentially even at high speeds. Even at 120km/h, the engine noise level is exceptionally low, and it does not become significantly louder at 150km/h. The engine is well-balanced harmonically and has almost no vibrations over the entire range, which is hard to believe for a reciprocating four-cylinder engine. The rev counter is redlined from 7000-8000rpm, but it easily over-revs in first through third gear, and the engine is so smooth that the fact that it is over-revving is not noticeable. The valve gear response is still perfect even at 8000rpm+.

At Yatabe, we did five or six laps of the 5.5km circuit at full throttle, maintaining an actual speed of 160km/h (about 6800rpm, 174km/h on the speedometer!), and the engine showed no signs of trouble, and we did not feel any psychological stress. Therefore, the potential cruising speed on the highway is high, and if the law allowed, we could maintain 140km/h (about 5900rpm) for a long time. In this kind of use, having a dry sump system gave us great psychological confidence.

This makes the car’s character primarily that of a high-speed cruiser, but the compact exterior dimensions and sharp acceleration also make it useful as a city runabout in crowded towns. The 4-speed gearbox has gear ratios that match the power characteristics well, the shift feel is excellent, and it can be rated highly overall in this kind of driving. If you push the engine up to 7000rpm, you can reach speeds of around 47, 84, and 123km/h in first, second, and third gears, respectively, and even using only up to 5000rpm in first and second gears, there is practically no car that can keep up with the Honda 1300 in a traffic light Grand Prix.

On the other hand, this high-revving engine is also very tenacious even at low engine speeds, with a top-gear minimum speed of 40-45km/h (below 2000rpm), and it easily maintains 50km/h in fourth, accelerating without any hesitation when you step on the gas. The engine’s flexibility and power reserve are clearly shown in the overtaking acceleration times in top gear: the acceleration times from 40-80km/h, 60-100km/h, and 80-120km/h are almost the same, at 12.5 seconds, 11.9 seconds, and 12.2 seconds, respectively. The acceleration in top gear continues unabated at 100km/h (about 4200rpm, close to the maximum torque point of 4500rpm), and it responds clearly when you step on the gas, finally slowing down after 130km/h. In conclusion, people who buy the Honda 1300 because they are attracted to its speed will be more than satisfied.

However, this high performance does not come for free. Fuel economy varies greatly depending on driving patterns, but in our case (70% city commuting, 30% on the highway), the end-of-month gas bill is more like that of a 1600cc GT than a 1300cc practical car. The overall average over a 1,400km test period was a dismal 7.5km/l. The best fuel economy recorded with the C/G 1300 77 was an average of 9.8km/l during the running-in period up to 1,000km. In our experience, this is unprecedented for this class of car. If you drive only in the city, the fuel efficiency may drop below 6km/l, and even under good conditions, such as a round trip to FISCO, the fuel efficiency was at most 8.5km/l. It is a small relief that regular-grade gasoline can be used.

The engine’s poor fuel economy is related to the fact that it is air-cooled. It is said that air-cooled engines heat up quickly and cool down quickly, but this is only half-true in the case of Hondas; they tend to heat up slowly and cool down quickly. It is true that the 1300’s engine warms up quickly in the summer (the same goes for water-cooled engines), and in fact it gets so hot that you can’t even touch the hood. However, from the beginning of autumn, we started to notice the poor warm-up characteristics. Even after warming up the engine for a few minutes, it is easy to stall if you don’t pull the choke and raise the engine speed to about 1500rpm, and it takes about five minutes of driving before you can fully release the choke. As we will explain later, the heater is also very slow to respond, and it takes about 10 minutes of driving before it starts to warm up the car slightly.

The crucial disadvantage of air-cooled engines compared to water-cooled engines is that they cool down easily. In winter, if you leave the car parked for two hours, the engine will cool down completely and you will have to start the warm-up process all over again. One of the reasons for the 1300’s poor fuel economy is that you often have to use the choke a lot. By contrast, water-cooled engines accumulate heat in the water, so there is little thermal change. Honda’s PR says that air-cooled engines are hassle-free because they don’t use water. However, modern water-cooled engines have sealed coolant systems that are service-free for two years, and as long as the thermostat is in good condition, they warm up quickly and maintain a constant temperature throughout the summer and winter. As a result, their heaters also work well, so no matter how you look at it, water-cooled engines seem to have the advantage.

Another point we would like to make against Honda’s insistence on air cooling is that the advantages of an air-cooled engine should be compactness and lightness, but in the case of the 1300, it is the opposite. First of all, it is heavy in absolute terms. The engine alone (including the dry sump oil tank) weighs about 180kg, which is at least 10kg heavier than a water-cooled engine (plus its radiator) in the same class, and it is by no means compact. It is certainly praiseworthy that the engine is so quiet that you would never think it was air-cooled, but the amount of weight, space, and cost that went into just making it quiet is a problem, and it has to be said that it has also reduced the passenger compartment volume, which is the most important thing in a passenger car, upset the weight balance, and adversely affected the handling. Air cooling is a natural choice for a two-cylinder minicar like the N360, but it is difficult to understand the positive reasons for adopting air cooling for a 1300cc engine (“What about Porsche?”, you may say, but that is an expensive two-seater GT).

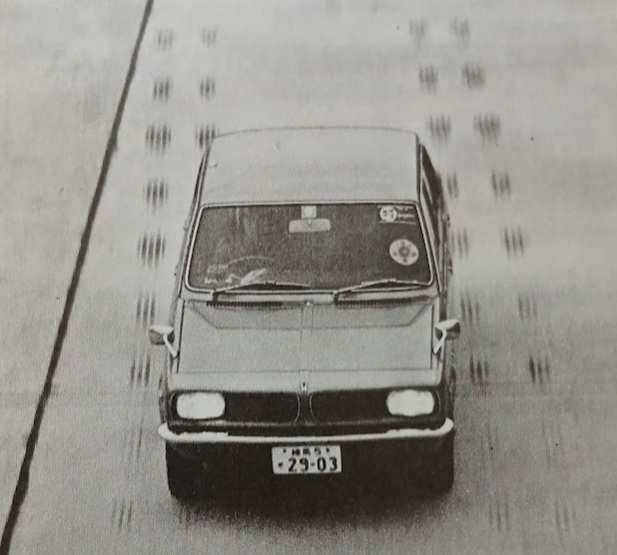

Now, let’s change the topic and talk about handling and stability. With a weight distribution of 61.7%/38.3% when unladen, the Honda 1300 naturally has excellent directional stability. This is a big advantage when cruising on highways (which are usually elevated, so there is almost always a crosswind). On the day that we drove the 1300 to Yatabe to accompany the test of the Fairlady Z, there was a strong wind (with gusts of 10m/s at a time). The Fairlady Z was blown about quite a lot at 150km/h, but in the 1300 that was transporting the test equipment, we found that even at 150km/h, it was hardly affected by the crosswind. Unfortunately, however, the Honda 1300 is quite sensitive to disturbances from the road surface. The steering wheel is easily deflected not only by streetcar tracks (which fortunately have become noticeably less common in Tokyo), but also by slight vertical ridges, and the tires tend to “walk” around on their own. This naturally depends on the condition of the tire tread, especially at the edges. In the case of the Dunlop GS1 6.2S-13 tires that were fitted to our car, wear was very fast, with only 50% of the tread remaining after 5,000km, at which point the straight-line stability worsened noticeably.

Tires have a huge effect on the handling of any car, but in the case of the Honda 1300 it is extreme. The Honda exhibits severe (we would say excessive) understeer, and in our opinion this excessive understeer should be attributed more to the tire performance than the suspension design. Simply put, the Dunlop GS1 6.2S-13 tires that came with the C/G 1300 77 (even though they were specially designed for this car, with an extremely low aspect ratio of 0.77) were completely unsuitable for the car’s performance. First of all, tire wear was abnormally rapid, with only 50% of the tread left after 5,000km, and the front tires were completely bald by 10,000km (though the manufacturer itself acknowledges that this wear rate is roughly standard for the 1300). The cornering power of the GS1 is low, and even when going around a street corner slowly at normal speeds, there is a great deal of squealing. The standard air pressures of 1.6kg/1.3kg (later revised to 1.7kg/1.4kg) are not so high as to cause problems, and with 2.0kg/1.8kg, the understeer is finally reduced to a level that can be tolerated during normal driving, and the ride comfort is not at all impaired.

Like the standard tire pressures, the suspension of the Honda 1300 seems to be too focused on ride comfort. The suspension absorbs both small irregularities and large wavy bumps in the road, providing a very comfortable ride in both the front and rear seats. In this sense, the Honda 1300 is more of a passenger’s car than a driver’s car.

In our opinion, however, the suspension is too soft for a car with this speed potential. In addition, the basic layout, with a relatively high center of gravity and an absolutely narrow front track (1245mm, compared to 1300-1370mm for European front-wheel-drive cars in the same class) results in a large load transfer between the left and right tires when cornering, and a very large amount of body roll. Furthermore, rubber insulation is used extensively in the suspension to soften impacts from the road surface. These various factors combine to make the understeer extremely strong when the car is pushed to the limit. It is good that the steering is very light even at parking speeds, and there is almost no kickback from the road surface, but the response is extremely slow. Even if you turn the wheel 45 degrees left and right at 100km/h, the car’s direction hardly changes at all. Since there is no mechanical play in the rack and pinion steering gear, this is simply an indication of the low rigidity of the steering system and the large slip angles of the tires.

You need to be careful when going around tight corners at high speeds (this is true for any car, of course). The most dangerous thing is to not fully understand the principle that “in front wheel drive cars, you corner while accelerating,” go into a corner in second gear or under full throttle, become surprised by how much understeer there is, and release the throttle midway through the corner. Going into the hairpins at FISCO, you need to turn the steering almost to full lock in the case of this Honda, but if you lift your foot off the throttle, it will suddenly spin out to the inside. In the same situation, the front-wheel-drive Subaru FF-1 is much less prone to this tendency, and its cornering posture is much more stable (but the ride is much less comfortable).

As mentioned above, the tires on the C/G 1300 77 had almost completely worn down by about 12,000km, so after consulting with Honda, we replaced them with Dunlop GS1 6.2H-13 tires, which are standard equipment on the sporty 99S model. In specification, these tires appear the same as the 6.2H-13 tires on other 99s, but they can be distinguished by the lack of white ribbons on the sidewalls. Surprisingly, just by installing these tires, the handling of the C/G 1300 improved by about 50%, and about half our complaints about the handling were eliminated. First of all, the squealing in corners almost disappeared, responsiveness improved dramatically, and cornering became much easier and safer. As for wear, we have only driven about 2,000km on these tires, so we cannot say anything definitive, but it does not seem to be much worse than the 6.2S-13s. The 6.2H-13 tires developed for the 99S are essentially the equivalent of six-ply tires, with a different cord angle for higher lateral stiffness, especially in the sidewalls. For a car like the Honda 1300, where the absolute value of the front wheel load is large and the load transfer between the left and right tires is significant, radial tires with low lateral rigidity are particularly unsuitable. At the same time, this six-ply-equivalent 6.2H tire does not impair the ride comfort at all. All things considered, this tire should be standard equipment on all Honda 1300s (the only drawback seems to be their high cost, but if they significantly reduce the possibility of accidents, then they are actually very cheap). In addition, the 4J x 13 wheels on this car seem to be too narrow, and moreover, they are not very rigid and bend easily, so when driving hard on winding roads such as those around Hakone, they deform from the side forces and the wheel caps can come off.

Front wheel drive vehicles tend to have a large turning radius, and the Honda and Subaru are prime examples of this, so unless the road is very wide, you won’t feel like attempting a U-turn.

Generally, it is difficult to design brakes for front wheel drive vehicles, but the Honda 1300’s brakes are well matched to its high speed potential, and can be given a passing grade. The front brakes are Girling type single cylinder (Annett type) discs with servos, and the rear brakes are drums with a Sumitomo Kelsey-Hayes type pressure control valve. The pedal force is always light, and they provide strong and stable braking force even at high speeds. Tests showed a braking performance of 0.99g with a pedal force of 40kg from 50km/h. The amount of nose dive is large at first (it hardly sinks any further after the first touch of the pedal), so it is especially noticeable when the brakes are applied frequently at low speeds in town. C/G uses a harsh method called “0-100-0” to test brake fade. In this test, we accelerate from 0 to 100km/h, apply 0.5g braking until the car stops, immediately accelerate to 100km/h and brake again, and repeat this ten times while recording the change in required pedal force. In the case of the Honda 1300, the initial pressure was 10kg, but by the fourth stop it was 15kg, and by the sixth stop it was 20kg. However, it did not increase any further after that, and the braking effect itself was stable, so the brakes can be judged as having sufficient fade resistance. The handbrake is in a good position behind the gear lever and works on the rear wheels, so once you get used to it, you can make Carson-style handbrake turns even on dry paved roads.

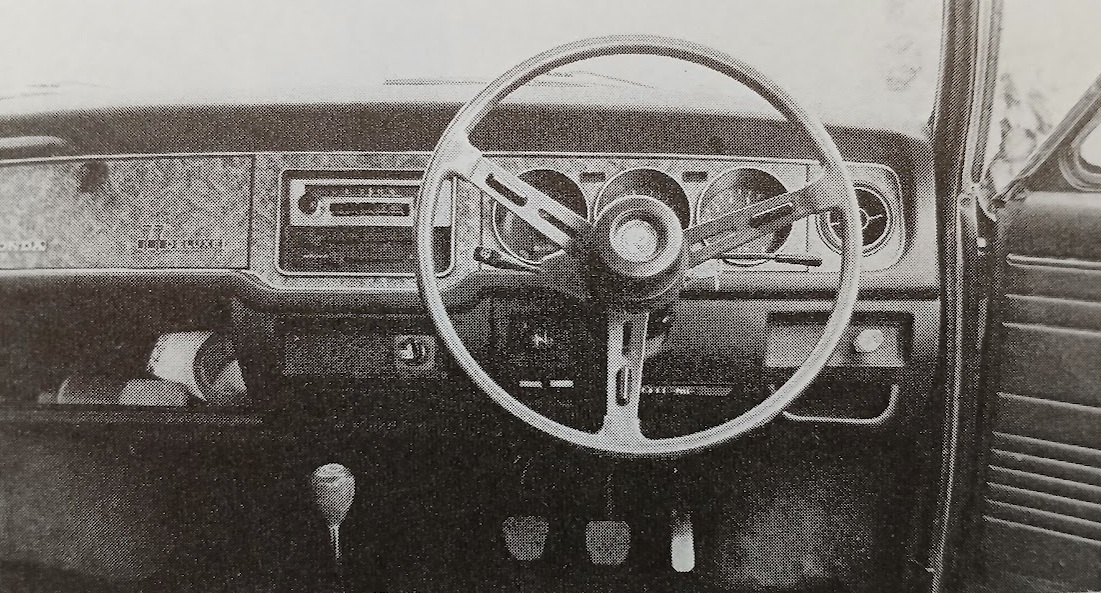

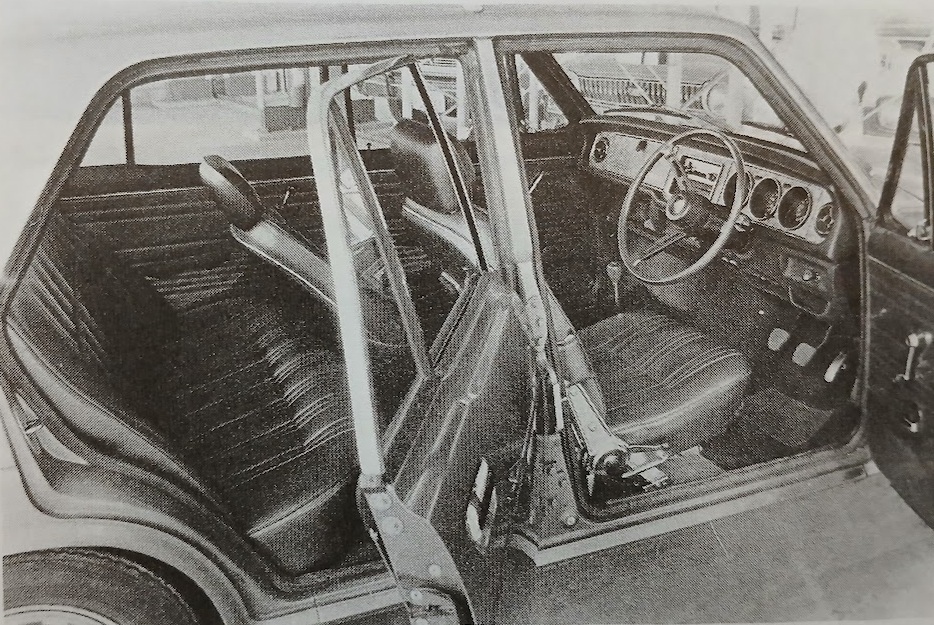

The interior is not spacious for a 1300cc class vehicle. The driving position is generally good, except that the pedals are offset to the left due to the intrusion of the wheel arch (which is quite obvious, at least at first). All of the instruments are easy to read. However, the design of the dashboard is somewhat clumsy-looking, and in the case of the Deluxe model, it is made of a cheap imitation wood trim that is not suitable for a mass-market car. The 77 Deluxe’s seats are made of hard vinyl leather, which can feel cold and hard in winter. The shape of the rear seats is good, and they are adequately comfortable, except for the short cushions. There are no intrusions from the wheel arches on either side in the rear, and the floor is flat, so three people can sit comfortably.

As mentioned earlier, the heating system doesn’t work very well. The Honda 1300 doesn’t have an independent heater, but simply ducts air from the engine cooling fan at the tip of the crankshaft. The air-cooled engine is slow to warm up, and in cold weather the engine tends to overcool itself due to the effect of the wind while driving, so it doesn’t work well as a heat source. At temperatures around 0°C, it takes 10 minutes for the heater to start working, and at least 20 minutes for the interior temperature to become moderately warm. At present, there is no optional front grille cover to prevent overcooling, and a heater for cold regions is still in the planning stages (using heat from the exhaust pipe, not a combustion type). However, the system is at its worst when dealing with high temperatures and humidity during the rainy season. There is no defogger independent of the heater, so if you try to defog the windshield, you have to use hot air (it’s very effective at speed, but weak when the car is stopped and idling), and you can’t do anything about how hot it gets inside. However, the vents on both ends of the dash are effective for ventilation.

In conclusion, for better or worse, the overall design of the Honda 1300 is too heavily influenced by its high-powered air-cooled engine. In a practical family sedan, the position that the engine occupies–its significance to the whole car–should not be so great.

(Supplement: from March 1970 issue)

In the February issue’s Honda 1300 road test, we wrote that the heater did not work well and that we wanted a front grille cover to prevent the engine from overcooling. We later discovered that this optional part is sold in cold regions and has finally become available in major cities recently. We installed it on our C/G 1300 right away, and would like to report on it. It consists of a steel front cover (800 yen per side) that covers the left and right front grilles, and a plastic skirt cover (1000 yen) that covers the air intake behind the license plate. We first installed only the left and right grille covers on the C/G 1300, and sure enough, the engine temperature rose much higher and warm-up became faster (even so, we pulled the choke out and kept the engine speed at 1500rpm for the first several minutes of driving). The heater became effective within about 10 minutes, and after 20 minutes, the interior actually became too hot at full throttle, so it was a great improvement in that sense. As a result, we don’t feel it’s necessary to install the skirt cover. However, the covers are removed too easily because they are only secured to the grille with a simple claw hook. Ours dropped off the car once, so we have been fastening them with wires from behind. Incidentally, the exhaust-heat heater we mentioned for cold regions (Hokkaido only) is installed at the factory and is not available in other regions.

Postscript: Story Photos